Vincent Coleman

by Chris Miller

Today, a final goodbye. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

On the morning of December 6, 1917, Vincent Coleman reported to his post on the north end of Halifax, Nova Scotia. He worked as a dispatcher for Canada's Intercolonial Railway. The Richmond Station where he worked lies on the shore of The Narrows - an inlet separating Halifax and nearby Dartmouth. Halifax was already a busy seaport on Canada's east coast, but World War I transformed it into a military port. The Canadian Royal Navy maintained the Atlantic trade routes and required all neutral ships to stop in Halifax for inspection. Submarine nets installed at the end of The Narrows had to be lowered to allow convoys in and out of the harbor. But this limited ship traffic and caused frustrating delays.

Impatient ships packed the harbor as usual that morning. At 8:45 am, two ships collided near Pier 6 about 750 feet from Richmond Station. The unladen SS Imo cut into the starboard hold of the SS Mont-Blanc, which carried 2600 tons of munitions bound for Europe. The Imo reversed engines to pull back, but the scraping metal sparked a fire that soon raged out of control. The Mont-Blanc's crew quickly abandoned ship.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

One sailor made it to the Richmond Station and warned the dispatchers of the fire and imminent explosion. Vincent Coleman and the others ran. Suddenly Coleman stopped. He realized that the #10 train carrying 300 people from St. John, New Brunswick was due any minute, and its track would take it right next to the burning Mont-Blanc. He returned to his post and repeatedly tapped the following message to other stations:

Hold up the train. Ammunition ship afire in harbor making for Pier 6 and will explode. Guess this will be my last message. Good bye, boys.

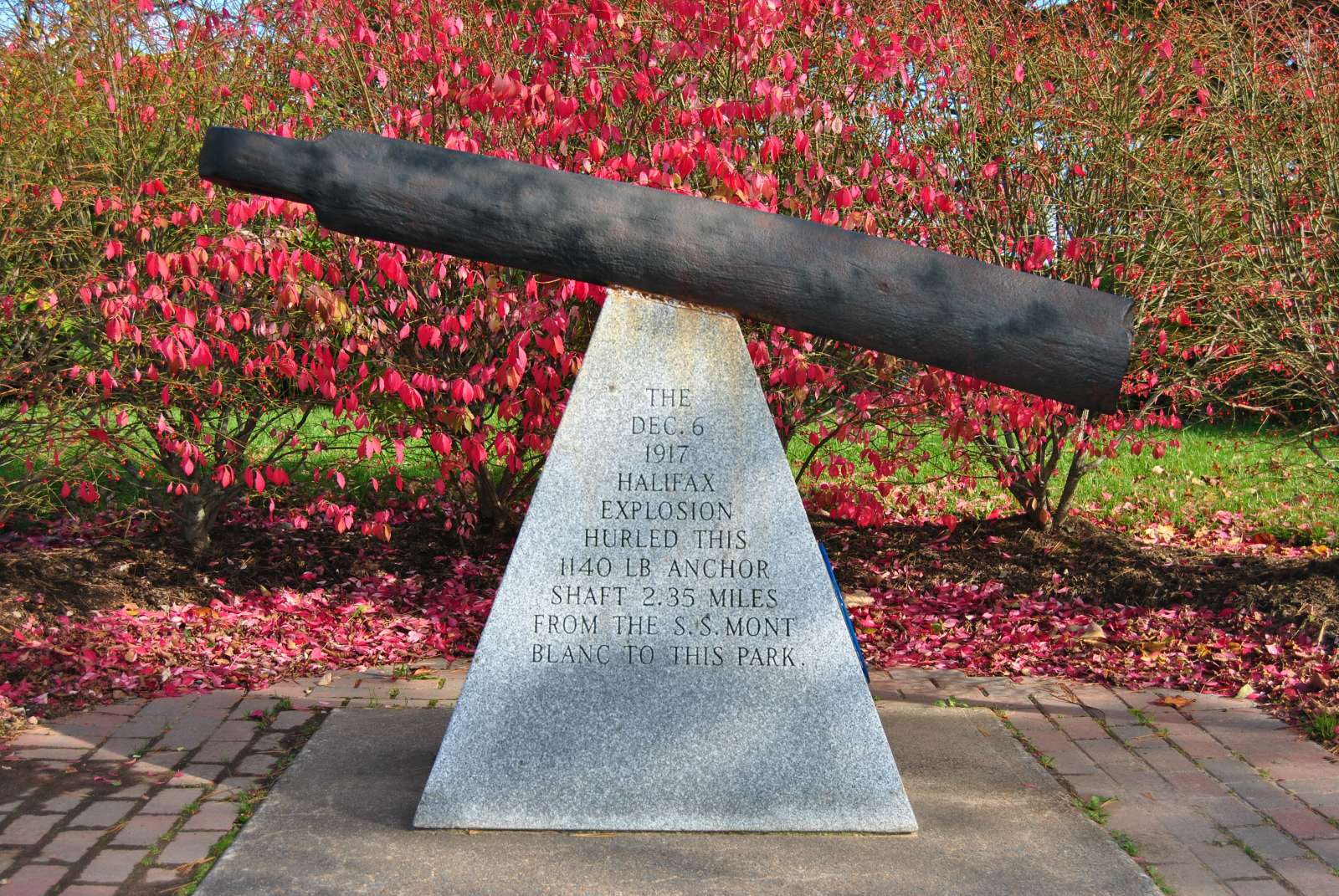

Twenty minutes after the collision, the Mont-Blanc's cargo exploded with a force one-seventh that of an atomic bomb. The shock wave leveled Halifax and Dartmouth and could be felt for 130 miles. The Mont-Blanc's anchor landed two miles away. Two-thousand people died and over 9000 were injured.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

The #10 train remained far enough away that it only suffered minor damage. It continued on after the blast, but stopped short of Richmond due to debris on the tracks. The passengers saw the devastation, then quickly became rescuers. They used the train's tools to pull survivors from the wreckage and tore bed sheets into bandages. The #10 became a hospital train, carrying the wounded to the Truro Station to the north.

Coleman's message also warned the other stations of the disaster. Otherwise, those dispatchers would have wasted hours wondering why Halifax went silent. Instead, they quickly mobilized rescue efforts, which arrived within hours. Good thing too. A blizzard blew into Halifax the next day, shutting down rail traffic. More relief trains couldn't pull in for two more days.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Vincent Coleman died trying to stop the #10 train and save its passengers. But his self-sacrifice saved countless others who would have surely perished without immediate medical attention. For his heroism, Vincent Coleman was inducted into the Canadian Railway Hall of Fame in 2004.

I'm Chris Miller, along with the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Vincent Coleman's body was found under the wreckage of the Richmond rail yards a few days after the explosion. Coleman's wallet, pocket watch, pen and telegraph key are on display in the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax.

Mont-Blanc pilot, Francis Mackey, recalls the Halifax 1917 explosion in this interview.

The Halifax 1917 Explosion was the largest man-made explosion in history - until the atomic bomb. Robert Oppenheimer (one of the lead physicists of the Manhattan Project) studied the effects of the Halifax 1917 Explosion when computing the strength of the atomic bombs being developed during World War II.

The explosion produced two other catastrophes. The blast blew through the windows of nearby buildings, knocking over lamps and stoves, which sparked numerous fires across the city. Also, the explosion vaporized the water in The Narrows. So for a brief moment, one could see the floor of the harbor. But the sea rushed in to fill the vacant space, culminating in a 60 ft. (18 m) high tsunami that flooded the cities.

An inquiry was launched to investigate the accident. Initially, the final report blamed that the Mont Blanc's captain, its pilot, and the Royal Canadian Navy's chief examining officer (who was in charge of the harbor, gates and anti-submarine defenses). But a series of appeals concluded that errors by both the Imo and Mont Blanc led to the collision. So no person or entity was successfully prosecuted for their contribution to the catastrophe.

More fascinating details about the Halifax Explosion can be found here and here