The Battle of Navarino

Today, we ask: when is a victory not a victory? The Honors College at the University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

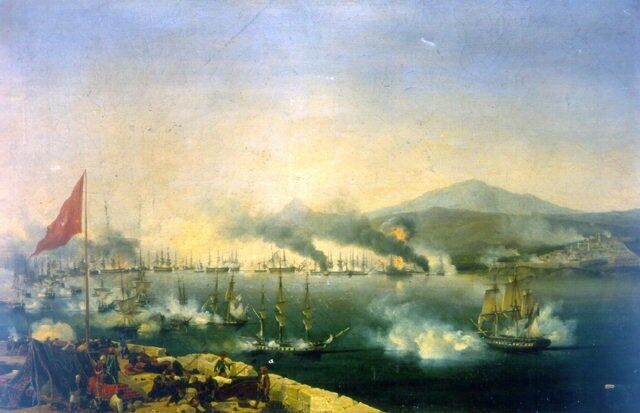

It's October 1827, and we're in Navarino Bay, off the coast of Greece. A Turkish armada faces an international coalition of British, French, and Russian warships, sent to enforce an armistice during the Greek Revolution. The Greeks had risen up six years before, and fought desperately to end nearly four hundred years of Ottoman rule. But the Turks were getting the upper hand, so Europe intervened to keep the Greeks from being annihilated by their overlords.

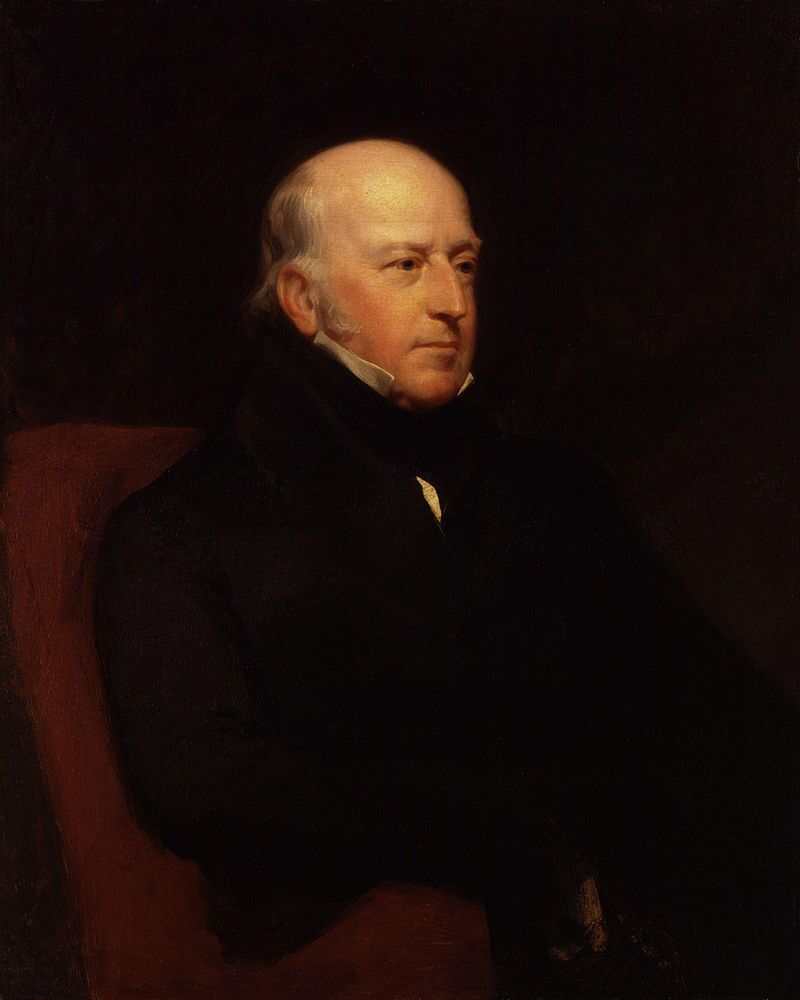

In command of the allied fleet is Sir Edward Codrington, an intrepid sailor. He's a 44-year naval veteran, and a hero of the Battle of Trafalgar. He's also a committed philhellene, sympathetic to the Greek cause. When the Turkish armada refused to respect the armistice, he boldly bottled them up in Navarino Bay. And now his ships stand at anchor, arrayed in front of the Turks in an impressive show of resolve.

The Battle of Navarino by Ambroise-Louis Garnerey. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons.

What happens next is the last major naval battle between sailing ships. The stand-off flares suddenly to open combat, with the ships firing at close range. Within a few hours the allies win a staggering victory, utterly destroying the Ottoman fleet. All over Greece the victory bells ring, and the European public hails Codrington as the hero of the hour.

So here's an interesting problem. Navarino was by any account, a great tactical victory. And because it reinforced the greater goal of keeping the Turks from ravaging Greece, it was also a strategic victory. But in the jenga of geopolitics, it was in the eyes of European leaders, a catastrophic victory. The Ottoman Sultan reacted by declaring jihad against Russia, triggering a whole new theater of war. This was a dangerous gamble. The British and French were dismayed, as they were counting on the Sultan to be a bulwark against growing Russian power. The victory also triggered a later civil war between the Sultan and the Pasha of Egypt, which threatened to rip the whole Middle East apart.

Portrait of Sir Edward Codrington (by Henry Perronet Briggs). Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In the corridors of power, Codrington was blamed for precipitating a total shift in the geopolitical situation. The King of England referred to Navarino as "an untoward event." European leaders hoped to make Greece an autonomous region still subject to the Ottoman Empire; after the victory, they had to accept it would be a truly independent state. But even the Greeks lost out here in the end, in that the Powers ultimately insisted that Greece be a monarchy, not a republic. So the Greeks were saddled with a German boy king, Otto of Wittelsbach.

The British Admiralty quietly punished Codrington behind the scenes, popular though he was. Was he too bold a sailor to do a diplomat's job? Or were allied interests simply too complex? They were tied, after all, to a war for freedom in Greece, a land of almost mystical significance to Western Europe. Perhaps the ultimate question is simply this: is 'gunboat diplomacy' really just a contradiction in terms?

I'm Richard Armstrong at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Bass, Gary J. 2008. Freedom's Battle: The Origins of Humanitarian Intervention. New York, Alfred A. Knopf. (see chapter 12 especially)

Dakin, Douglas. 1973. The Struggle for Greek Independence, 1821-1833. Berkeley, U California Press. (pp. 226-230)

Woodhouse, C. M. 1965. The Battle of Navarino. Hodder and Stoughton, London.

[no author]. 1829. Life on Board a Man-of-War, including A Full Account of the Battle of Navarino, By a British Seaman. Glasgow, Blackie & Fullerton. Available online through Google Books.

This episode was first aired on July 19, 2016