Electioneering in Ancient Rome

Guest post by Richard Armstrong

Today, how to get elected in ancient Rome. The Honors College at the University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Let's face it, we all get a little cynical during election time. There are a lot of staged photos, vague promises, blatant overtures to interest groups. And let's not forget all the mudslinging. As Adlai Stevenson once said, "the hardest thing about any political campaign is how to win without proving that you are unworthy of winning."

Well, take heart at least that this is not just an American problem. There is a fascinating document from ancient Rome all about electioneering. It purports to be a handbook written by Cicero's brother in the first century BC. It dispenses clear advice on how to win election to the highest office in the Republic of Rome: the consulship.

Every day as you go down to the Forum, the handbook states, you must repeat to yourself: "I am new, I seek the consulship, this is Rome." These three things explain a lot about the candidate's predicament. Cicero was a "new man," which in Rome meant someone who did not come from one of the great families that controlled politics -- the Kennedys, Clintons or Bushes of the day. His rivals were from such families, and had consuls in their family's past, giving them the air of inevitability as candidates. Cicero was an outsider, and he was the first of his family to enter the Senate. For such a man to seek the highest office, well, that was a stretch.

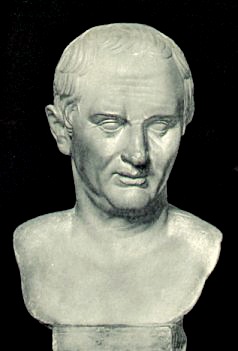

Sculpture of Cicero. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

But, as the handbook says, he has some things on his side: he is feared and respected in the law courts for his powers of persuasion. Among his friends are all the people he's defended, but also a good swath of the middle class: the business people and public contractors, big wigs from small towns'in sum, the men of his own social class, all good voting citizens. Young aristocrats, too, flock to him for instruction in public speaking. He must build on this base.

Always be seen with an entourage, the handbook advises. Let your house be full of supporters from early morning; make sure there are people from all social classes. Go down to the Forum with a throng, to make yourself look like a person of influence. Make sure to call on people by name, and more than once. Promise the aristocrats that you are not all that supportive of the common people'you only appear to be when politically necessary. But then court the common people by putting on a fine show, with the best in outward appearance and dignity. But spice it with some scandalous talk of the crimes, lusts, and briberies of your rivals. Promise senators you will uphold their authority, businessmen you will guarantee peace and prosperity, and the common people that you really care about their welfare. Whatever you cannot promise to do, decline it gracefully, or better yet, don't decline it at all. A good man will say no, but a good candidate'll keep his options open.

Sound familiar? These elections were held in a city where all politics was still literally face-to-face. Our media circus may have amplified the arena, but the game hasn't changed that much in two millennia. So just sit back and enjoy the show.

I'm Richard Armstrong at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Note:

This text is attributed to Quintus Tullius Cicero and purports to be from 65-64 BC, but scholars have long debated whether it might be a forgery or some kind of rhetorical exercise. Even if it is not by Quintus, it reflects ideas close to the time it pretends to be from, and is therefore interesting reading all the same.

Source:

Handbook of Electioneering (Commentariolum petitionis) edited by D. R. Shackleton Bailey, translated by Mary Isobel Henderson. Loeb Classical Library, Cicero vol. XXVIII, pp. 395-445.

This episode was first aired on March 15, 2016