The Last Galleys

Today, we finally put galley slaves to rest. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Our technology has, on the whole, freed us. But, freedom has always seesawed as new technologies have come and gone. Oars, for example, gave us freedom of motion, but few people other than slaves have ever pulled oars in a galley.

We all know that galleys were widely used in the ancient Mediterranean world. But when do you suppose navies quit using galleys and galley slaves? Well, they didn't die out until late in the reign of Louis XIV, in the early 1700s.

A century and a half before, the King of France decreed that all galley prisoners would serve at least ten years. Surviving for ten years in a galley was no mean trick. Galley slaves were branded with the letters G-A-L. They were forced to eat, sleep, and labor chained in their own filth. When one collapsed, he was simply chucked overboard. Mercy dictated that his throat first be cut, so he wouldn't have to suffer drowning.

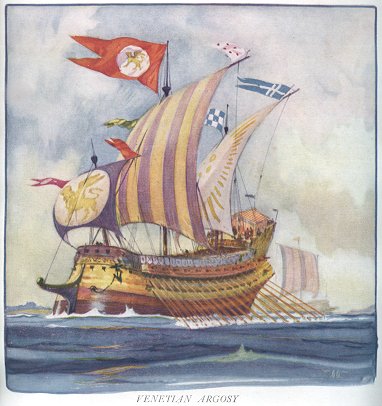

Seven years after the ten-year minimum sentence was imposed, the last great battle among galleys was fought -- the Battle of Lepanto. In 1571 two great galley armadas formed up in a battle for control of the Eastern Mediterranean. These ships carried some sail, but their main engines were convicts and prisoners of war. Spain and the Papal states gathered over 200 light galleys and six Venetian galleasses. A galleas was a huge slow-moving oar-driven gun platform. The Turkish forces were larger but not so well equipped. The two armadas finally found each other near the Greek town of Lepanto, in that strip of water that bisects Greece. The Europeans won, but not until 16,000 people had been killed and 8000 more wounded.

Seven years after the ten-year minimum sentence was imposed, the last great battle among galleys was fought -- the Battle of Lepanto. In 1571 two great galley armadas formed up in a battle for control of the Eastern Mediterranean. These ships carried some sail, but their main engines were convicts and prisoners of war. Spain and the Papal states gathered over 200 light galleys and six Venetian galleasses. A galleas was a huge slow-moving oar-driven gun platform. The Turkish forces were larger but not so well equipped. The two armadas finally found each other near the Greek town of Lepanto, in that strip of water that bisects Greece. The Europeans won, but not until 16,000 people had been killed and 8000 more wounded.

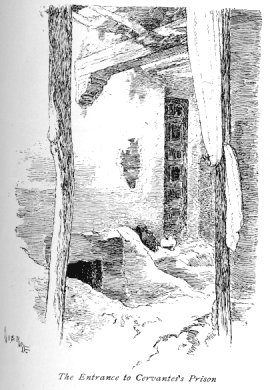

A young Spanish soldier, not yet 24 and sick with fever, took three bullets in that battle. His name was Miguel de Cervantes, and one of the bullets ruined his left hand. He wrote that the fight was "the greatest day's work in centuries," but he also lived to write Don Quixote de la Mancha. And there he painted armed combat in far more complex terms.

For all its size, the battle of Lepanto was as anachronistic as Don Quixote himself. It was the last great clash of dinosaurs. Galleys spent another 150 years dying out, while the technology of sailing ships raced on ahead. The 16th century galleon was so named because it represented the galley modernized and reshaped into a pure sailing ship.

Technology gives the gift of freedom, all right. But the long survival of anything as terrible as slave-powered galleys tells us we aren't always as quick to accept that gift as we ought to be.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Stokes, G.P., Last Galley Battle. Military History, August, 1989, pp. 26-33.

The basement cell where Cervantes was later imprisoned in La Mancha for his political beliefs