Archimedes to the Rescue

Today, Archimedes to the rescue. The Honors College at the University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

You've heard the expression eureka! I'm sure. It comes from the Greek heureka: I have found [it]. We're told this phrase became proverbial when Archimedes discovered the principle of displacement still basic to fluid mechanics. It essentially means the buoyant force exerted on any body placed in a liquid is equal to the weight of the liquid displaced by that body's immersion. This turns out to be a great way to determine the volume of an irregular object. Every middle-schooler knows the story how this came to him in a flash when he sat down in the bathtub. He then ran down the street naked shouting, "I have found it!" (If this is true, Archimedes is perhaps the first known streaker.)

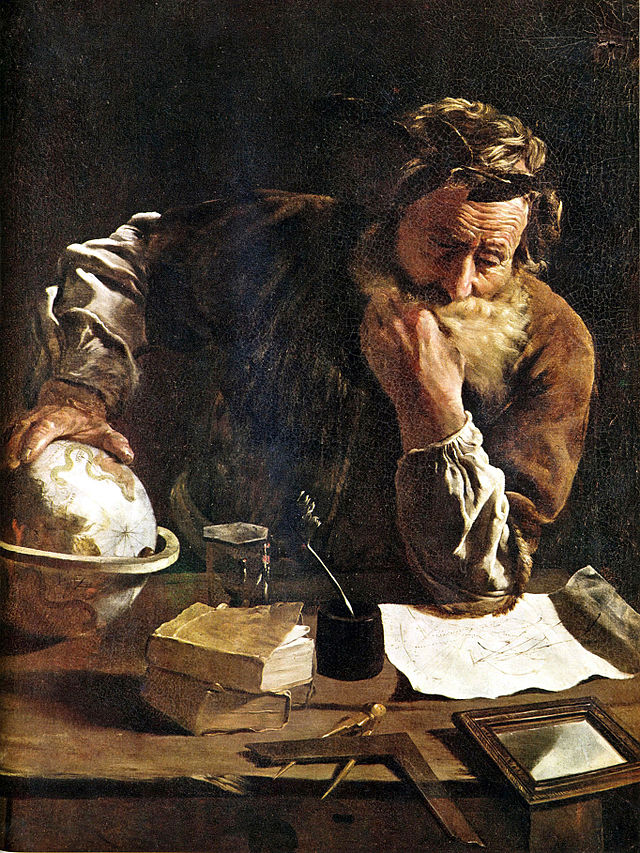

Archimedes, by Domenico Fetti, 1620. Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons

But what exactly was the problem he was seeking to solve in the tub? Truth is, he had a very practical problem. He was helping the ruler of his native Syracuse to detect a scam. Archimedes used this discovery to determine whether a golden crown commissioned by the ruler had been heavily alloyed with silver. Since the finished crown displaced more water than a mass of pure gold equal to what the ruler had originally given for it, Archimedes demonstrated the crown was less dense, and therefore, couldn't be pure gold as promised.

Years later, the inventive mind of Archimedes came to his city's aid on a much bigger problem: the Romans. Syracuse had been an ally of Rome, but after Hannibal invaded Italy, the city switched loyalties and sided with Rome's enemy, Carthage. A huge Roman force came to storm Syracuse by land and sea, but found itself stymied by Archimedes' war machines.

He devised a variety of catapults of different sizes that could fire at a number of ranges. He made openings in the walls, from which deadly iron darts could be fired at a man's height. He even devised massive machines capable of seizing a ship's bow and capsizing it, causing the Roman commander Marcellus to comment that the Greek was using his ships to ladle seawater into his wine cups. Harder to believe is the later story that he created a huge mirror that he focused like a death ray to zap the Roman fleet. Sounds cool — but it seems unlikely. People still like to try this out for fun all the same. But all our sources tell us the Romans were completely dumbfounded by the mathematician's war machines. Marcellus called him a "geometrical Briareus." Briareus was a mythical hundred-armed monster.

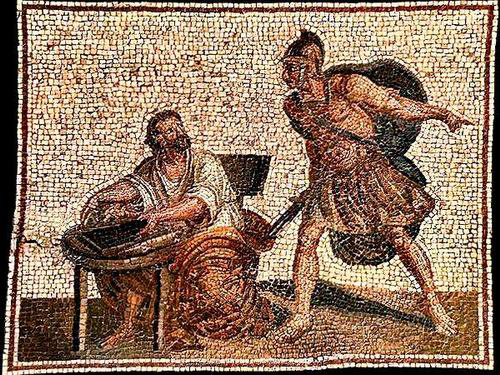

Death of Archimedes, 16th century copy of an ancient mosaic. Photo Credit: www.livius.org

In the end, the relentless Romans still managed to take Syracuse; but Marcellus was eager to spare Archimedes' life. The practical Romans, after all, always admired a good engineer. Now, there are many versions of the story of Archimedes' death. But they all have in common one thing: the Roman soldiers who burst into his home found him totally absorbed in a problem he was working out with a diagram. He put up a fuss at being pulled away from his work before it was finished, and a soldier hastily killed him to Marcellus' utter dismay. The old genius was one eureka short this time, and paid for it with his life.

I'm Richard Armstrong at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Jaeger, Mary. 2008. Archimedes and the Roman Imagination. U Michigan P. [A good work that examines many of the great anecdotes of Archimedes' life as retold by the Romans.]

There have been various attempts to prove or disprove the effectiveness of "Archimedes' death ray" against Roman ships, most notably on the television program Mythbusters.

This problem was discussed as far back as Engines episode 252 by John Lienhard. (See Episode 252.)

This episode was first aired on March 24, 2015