Forgetting Names

Today, let us forget names. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run and about the people whose ingenuity created them.

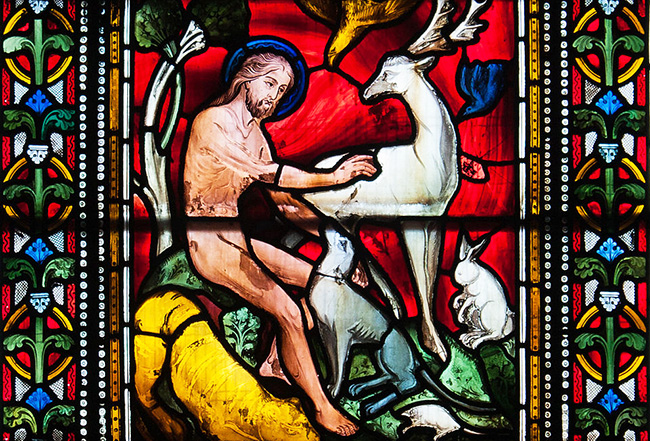

Naming is an ancient human fixation - linked to power and authority. How does Genesis tell of Adam's importance? It says he was empowered to name birds and beasts. Today, bosses often assert power by nicknaming underlings. iPhones let us nickname the people we often call. We are still empowered by naming.

This stained glass window in Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin, depicts Adam naming the animals. (Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.)

And we value our own names; we flinch when they're mispronounced; we like to hear them said. That's why fund-raisers put as many names as they can on new buildings - one on the building itself, several on special rooms, many more on donor plaques.

The famous bullfighter, Manolete, died after he stood his ground too long before a charging bull. Someone asked, as he lay bleeding, why he hadn't moved. "For that I am Manolete," he replied. His name, it seems, was more important than his life.

All this naming goes a bit crazy in our technologies. Think about diseases: Yellow fever and bubonic plague are identifiers that tell us something. But I doubt one listener in a thousand will recognize Kahler's, Forbes or Pott's disease. Once we say the clinical name of Kahler's disease, multiple myeloma, it's clearly a kind of cancer.

Or take the units of frequency: cycles-per-second. It was renamed the hertz in 1960. What a silly thing to do! Once it was self-explanatory. Now it is not.

Astronomers have wisely tried to skirt this sort of naming. They keep ancient astrological naming since it provides useful mnemonics. Still, they are under constant pressure to honor this or that person. Keepers of the periodic tables have pretty much caved in to the use of people's names. But ideas ultimately trump names.

This huge skyscraper stands isolated on the west side of Houston, TX. For years it was named Transco Tower. At this writing it is Williams Tower. Whatever it is called in the future, the Tower remains the Tower. (Photo by John Lienhard)

Think about our precious treasury of ideas. They're so valuable that we want to name them as well. We put Edison's name on the light bulb and Bell's on the telephone. But they were only two among countless others who shaped those ideas. Shakespeare had something to say about that in A Midsummer Night's Dream. His character Theseus pondered the human imagination and said,

The poet's eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to Earth, from Earth to heaven.

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

New ideas are born in that fine frenzy of thinking. We eventually bring them home to earth where we can name them. Call an idea: Relativity Theory, call it the Odyssey, call it Steam Engine.

Sure, people gave us those ideas. But power and identity fade while the fruit of human thought remains. Good ideas like the wheel or the arch are in use long after their inventor's names have faded away. And that is, in fact, a good thing.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

From Genesis 2:20, "And Adam gave names to all cattle, and to the fowl of the air, and to every beast of the field;"

The death of Manolete is recounted in Life Magazine, April 29, 1946. See this Wikipedia list of eponymously named diseases (it is long.) For the history of the change from cps to hertz Click Here. Theseus' speech begins Act 5, Scene I, of A Midsummer Night's Dream. You may read it here.

This episode was first aired on August 15, 2014