Hypnotic Crimes

Today, hypnotic crimes. The Honors College at the University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

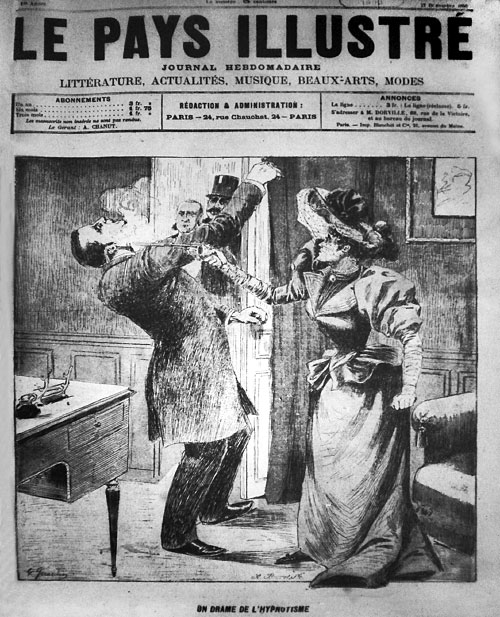

Paris, 1893. A young woman waits anxiously in a doctor's office. The doctor finally arrives; they go into the consulting room. She immediately demands 50 francs from him. He offers excuses, and as he rises to escort her out the door, she shoots him in the head. He has become the victim of a terrible irony.

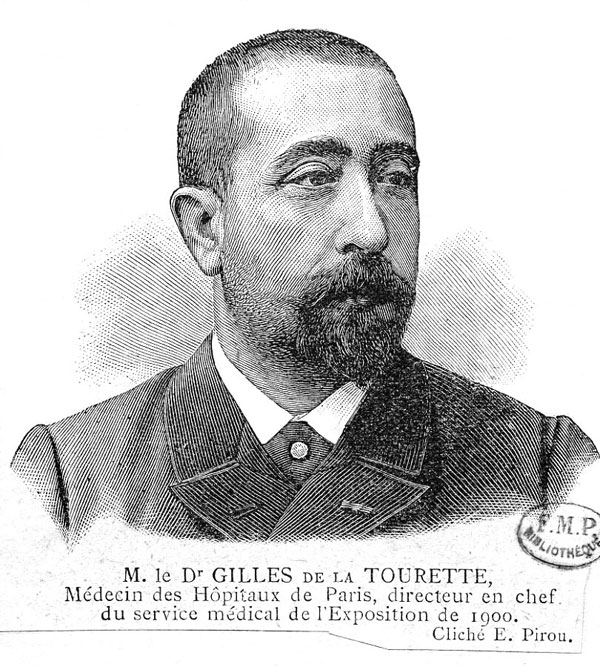

The doctor is Georges Gilles de la Tourette, known today for chiefly for Tourette's syndrome. He was a pioneering neurologist, attached to the great teaching hospital in Paris known as the Salp'tri're. There the famous neurologist Charcot began the vast enterprise of constructing modern neurology. But strange new things happened at the Salpêtrière, like the clinical use of hypnosis.

Charcot's school firmly believed that if you could be hypnotized, you had a clear hereditary tendency to hysteria. That was the bad news. The good news was they were also convinced you could not be hypnotically driven to do things against your moral conscience; for example commit a crime. But a rival school at Nancy saw it differently: in their view, hypnotic suggestion is so powerful one could be made to do terrible things. Hypnotism has the power to make you an amoral automaton.

This debate was chiefly waged in lecture halls, until a chance event drove it into the courts. The Gouffé affair was a notorious case of murder, where a young woman and her lover conspired to strangle a bailiff. It was a futile crime, as they found little money on him. Soon they fled Paris with the body stuffed in a trunk. The couple later went their separate ways, but eventually the woman turned herself in and fingered her accomplice. Once on trial, her attorney made the claim that she had been hypnotized by her lover and forced to commit the murder against her will.

A doctor from the school of Nancy rushed in to give testimony in court. Yes, one can indeed be forced to commit crimes under hypnotic suggestion, he argued. But rival proponents from the school of Charcot tore this "expert" testimony apart. Outside of a few laboratory experiments, no such crime had ever been proved. In the end, the defense collapsed, the woman was sentenced to twenty years hard labor and her lover was sent to the guillotine.

Gilles de la Tourette was ecstatic at his party's victory in this case. He published a gloating epilogue soon after the verdict. Full of scientific pride, he declared the triumph of his school's ideas.

But just two years later, this woman showed up in his office. She claimed she had been hypnotized at the Salpêtrière, and that she had "lost her will." Having been reduced to such a helpless state, she demanded payback. When he did not comply, she shot him. Suddenly Gilles de la Tourette was written up in the papers as the latest victim of hypnotic crime, and his rivals delighted in his plight. But he recovered from his wounds, and the woman proved quite disturbed; hypnotism was not the cause of her problems. And yet, the fascination of hypnotic crime would endure well into the 20th century. Regardless of its scientific standing, the idea remains compelling. For it is a drama of the human will.

I'm Richard Armstrong, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Sources:

"Eyraud to be guillotined." New York Times December 21, 1890.

Gilles de la Tourette, Georges. "Epilogue: un proc's célèbre." Paris : Progrès Médical, 1891.

Guinon, Georges. Attentat contre Gilles de la Tourette. Progrès Médical 1893 (2):446.

Mercier, Désiré. "Les suggestions criminelles. D'bat contradictoire au Congrès de neurologie de Bruxelles." Revue néo-scolastique 4:16(1897)409-415.

Walusinski, Olivier and Duncan, Gregory. "Living His Writings: the Example of Neurologist G. Gilles de la Tourette." Movement Disorders 25:14(2010)2290-2295.

On the Gouffé murder, you can read the exciting chapter in Harry Brodribb Irving's A Book of Remarkable Criminals (London and New York, 1918), pp. 305-328 and online here: http://www.globusz.com/ebooks/Criminals/00000028.htm