Smartphones/Wise Phones

by Roger Kaza

Today, smartphones vs. wise phones. The University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

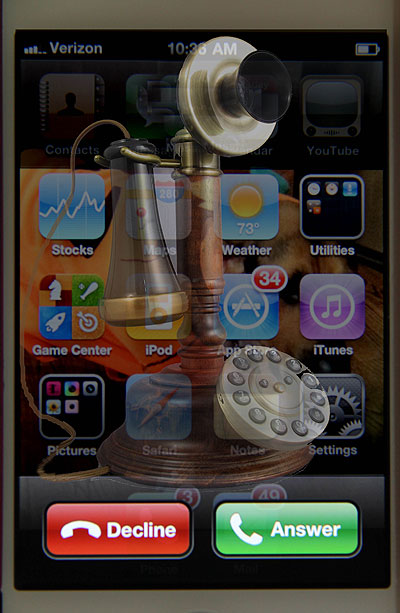

The PBS drama series Downton Abbey, set around World War I, has an episode where the Crawley family household gets its first telephone. Carson, the head butler, tries out a slew of various greetings, since no one is quite sure yet the proper way to answer a phone. Of course in those days it goes without saying that when the phone rang, you answered it. What a novel concept. Our so-called smartphones have sort of stopped living in the present moment. Instead, every call forces a decision. Answer now, or postpone the conversation to voicemail. We're also expected to gratefully embrace call waiting, call forwarding, caller ID, caller block, etc etc, options the Crawleys couldn't have dreamt of a century ago on their quaint candlestick phone. No doubt these tweaks seem like major improvements in phone technology, but what I'm wondering about lately is: do they also improve us along the way?

A choice that wouldn't have occurred to the Crawleys

I looked around for some allies supporting my point of view. Science reporter Ira Flatow says he had an epiphany after September 11, and so he canceled his call waiting. He decided that whomever he was talking to at that moment always took precedence over any other caller. That old-fashioned busy signal, seen in this light, seems so civilized and practical. It says, I'm available, just talking to someone else right now. Please call back.

And voicemail? Answering machines have a curious history. They were popular in the 1930s among Orthodox Jews, who weren't allowed to answer the phone on the Sabbath. But of course you would answer the phone any other time ... what better time than the present? When cassette tape answering machines first took off in the 1970s, we recorded cute, creative outgoing messages, complete with music. If you can't get a hold of me, then at least let me entertain you for a moment. That fad didn't last long. Nowadays a robotic female voice takes my call as often as not.

Caller ID must have seemed like a great idea. Know in advance who's on the other end. But, what happened to that cool thing called surprise? Isn't not knowing something sometimes just as fun as knowing? In pre-caller-ID days, you picked up the phone because, well, it could be your sweetheart. That's a nice surprise. Of course telemarketers are sometimes an unwelcome interruption. But, you can always practice patience by graciously declining their offers. Or, take a vacation in New Orleans, as my family did after one irresistible telemarketing pitch. It was wonderful.

Fortunately, it's good time to be a Luddite. Look around and you can find smartphone apps that will, yes, send your caller to a busy signal. Or, if you can't answer, it just rings — no voicemail. Another app will erase any log or record of who has called. And there are still others that block caller ID in both directions. Combine all of the above and, voil', you've just recreated that wise old Downton Abbey phone, a simple tool that lives entirely in the present, remembers no past, and always surprises you.

I'm Roger Kaza, from the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Achieving my retro Downton Abbey phone via smartphone apps is probably easier said than done. Many 'busy signal' apps are actually designed to thwart your caller from ever getting through to you. 'I'm always too busy to talk to you,' is the snarky message, instead of 'please call back.' Also, some apps require 'jailbreaking' the phone's operating system to implement, since they eliminate features the manufacturer insists we must want. Needless to say, I believe a clever hacker could recreate the Crawley family phone. A low-tech solution to accomplish much of the above might be to instruct your cell phone provider to disconnect voicemail and call waiting, and then simply avoid looking at the screen when you get a call. Try it! Outgoing caller ID can usually be blocked by dialing *67 prior to the number. Landline phones, not discussed here, may be easier to revert to their former state. (I realize these suggestions will probably find little traction among my latest-tech-savvy readers, but it's important to note that we still have more options than we think.)

The central point that fascinates me is how mere information, presented quite differently, profoundly influences our response to it.

Contrast the following:

1. A smartphone 'ringing' (which usually means a catchy melody), an identified caller, and two equal-sized button options, 'Decline' or 'Answer.'

Or

2. A clamoring bell whose only inferred message can be, 'someone is trying to reach me.' Which is more persuasive?

Or you can just go faux-retro

The telemarketer-prompted Kaza family vacation to New Orleans was fortuitous timing, as the city was destroyed by Hurricane Katrina just a few months later.

A history of answering machines.

Candlestick phone image courtesy Oldphoneworks.com

Photos by R. Kaza.

This episode was first aired on March 14, 2012