Flintknappers

Today, we meet some ancient flintknappers The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The term Stone Age echoes in our ears from childhood. Our early images of Cave Men -- hairy cartoon figures with big clubs -- has undergone successive refinement as we've learned more about the Mesolithic and Neolithic Eras -- the development of agriculture, weaving, pottery, house building, and more.

Yet the world stone lingers -- or its Greek antecedent, lithos. For this period is defined by stone-working. And, since it lasted for two and a half million years, we might well ask just how stone-working advanced over that time.

The earliest stone-working consisted of breaking rocks to form simple hammers and scrapers. A shallow piece broken off a rock will have a sharp edge that can be used, say, to scrape leather.

Three views of a 1.7 million year old Oldowan chopper -- one of the earliest examples of stone industry from a private collection. Source: Melka Kunture, Ethiopia.

But artisans of the later Mesolithic Era would flake chips off slabs of hard, brittle materials like flint, chert, obsidian, and chalcedony. They formed amazingly delicate knives and spearheads. That skill has come to be known as flintknapping. Flintknappers might wrap the hand that held the flint in leather for protection. With the other hand, they'd press a stone or bone implement into the edge of the slab to remove small chips, leaving behind a slightly serrated, viciously sharp, cutting edge.

Sometimes they'd shape that part on the surface of a larger core slab, then fracture it loose from the core. The result shows scallops on one side and is smooth on the other.

Those techniques are called pressure flaking, since carefully increasing pressure breaks the precise flake loose, in the precise place. Until recently, we'd thought such skills had arisen in the past 20,000 or so years. The Clovis culture of early Native Americans is one whose people made distinctive spearheads. Their graceful curves formed a profile like that of a Buck Rogers space ship.

Those techniques are called pressure flaking, since carefully increasing pressure breaks the precise flake loose, in the precise place. Until recently, we'd thought such skills had arisen in the past 20,000 or so years. The Clovis culture of early Native Americans is one whose people made distinctive spearheads. Their graceful curves formed a profile like that of a Buck Rogers space ship.

And, speaking of space ships, here's a time capsule for us to ponder. Anthropologists have been working for over two decades at Blombos Cave on the south coast of South Africa. That site has repeatedly upset archaeological timelines. Blombos' latest revelation is that Africans not only did this highly refined flintknapping, they'd added another wrinkle as well. They'd found that, by heat-treating a form of silica called silcrete, they could form just the hard brittle material they needed for spear points.

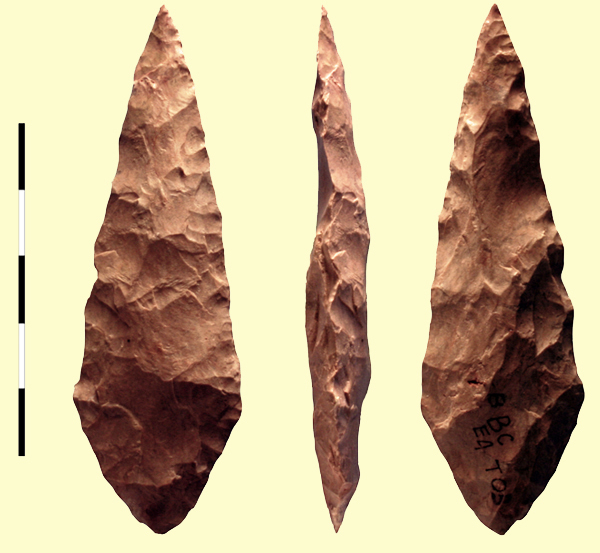

Three views of a bifacial silcrete point from Blombos Cave, South Africa; scale bar = 5 cm. Compare this roughly 75,000 year old point with the 1.7 million year old chopper above and the roughly 12,000 year old Clovis point above.

The catch is: the people who lived in and around Blombos Cave did so in a remarkably distant past -- between 75 and 80 thousand years ago. That long ago they were doing pressure flaking and heat treating to create truly artistic forms.

I've spoken before about the "Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's court problem" -- the idea that, if we were placed in some remote past, we'd have far less than we might think to tell our forbears. Well, I guess we might indeed be humbled by the highly-honed ability of these ancient technologists.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we are interested in the way inventive minds work.

V. Mourre, P. Villa, C. S. Henshilwood, Early Use of Pressure Flaking on Lithic Artifacts at Blombos Cave, South Africa. Science, Vol. 330, 29 Oct., 2010, pp. 659-662.

See the Wikipedia entries on Lithic Reduction, Blombos Cave, and Stone Age. All images are courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

This episode was first aired on August 8, 2011