Winged Words

by Casey Dué

Today, classicist Casey Dué listens to the Homeric epics. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

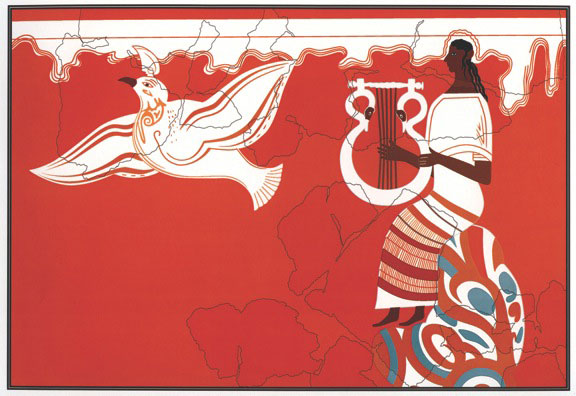

The Iliad and Odyssey consist of "winged words," to quote a common phrase in Homer. The ancient Greeks actually thought of poetry as being in flight. One Bronze Age wall painting shows a bird emerging from a bard as the embodiment of his song. This is because poetry was performed, not read. The epics each contain well over 13,000 verses, but they were not composed using the technology of writing. They were composed orally, on the fly and in performance, as the poet spun myth to life before his audience.

In the Odyssey, bards are depicted performing at banquets. These passages are fascinating windows into how ancient audiences imagined the creation of epic poetry. The process described is entirely oral — the Greeks believed that Homer himself was blind. This single poet "Homer" was almost certainly just an invention of tradition; yet he was not invented as a writer, but as a singer of tales.

Wall fresco from the Bronze Age palace at Pylos in Greece.

When the bard begins one of his tales in the Odyssey, he asks the Muse to pick up a story thread: the poet "weaves" his tale as he goes along, creating a beautiful tapestry of the glorious deeds of heroes. Did you know our word text comes from the Latin word to weave? Think textiles. Epic poets in ancient Greece were all men, but weaving was decidedly women's work. How can the acts of weaving and poetic composition be so connected? We have to wonder if the songs of women ever played a role in the creation of these epics. There are some tantalizing passages to consider. The first time we ever see Helen in the Iliad, she is "working at a great web of purple linen, on which she was embroidering the struggles between Trojans and Achaeans." Ares had made them fight for her sake. I expect Helen's version of the story would be much different than Homer's.

But a woman's perspective does seem to underlie many of the most beautiful passages of Homeric poetry. The deaths of flourishing young men are lamented with imagery drawn from the natural world: flowers that bloom and fall too quickly, trees that are cut down before their time.

This leads me to another passage about weaving. It's about Andromache, the wife of Hektor. He's the Trojan whom Achilles kills at the climax of the poem. Andromache has not yet heard the news. She is "at her loom, weaving a double purple web, and embroidering it with many flowers." She doesn't yet know that her husband is one of those flowers. In this way he is not unlike that hero that killed him, Achilles. Achilles' mother complains that she was "so unfortunately the best child bearer" because her glorious son, whom she tended like a tender shoot in an orchard, is destined never to return home from the Trojan War.

A song, like a hero's life, is fleeting. So how does a dynamic oral tradition become a fixed and permanent written text? We're not sure. But the ancient expression "winged words" gives us an important clue as to how to view these ancient texts: they have to be living things, birds in flight, and they only come to life in performance.

I'm Casey Dué at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Casey Dué is Associate Professor and Director of Classical Studies at the University of Houston, as well as Executive Editor at the Center for Hellenic Studies in Washington, DC. Publications include Homeric Variations on a Lament By Briseis (Lanham, MD, 2002), The Captive Woman's Lament in Greek Tragedy (Austin, TX, 2006), and Iliad 10 and the Poetics of Ambush: A Multitext Edition with Essays and Commentary(Cambridge, MA, 2010). She is the editor of Recapturing a Homeric Legacy: Images and Insights from the Venetus A Manuscript of the Iliad (Cambridge, MA, 2009) and the Homer Multitext (http://www.homermultitext.org).

Endnotes:

The orality of the Homeric Epics was demonstrated most thoroughly by the fieldwork and research of Milman Parry and Albert Lord, who compared the evidence from the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey to the then still flourishing South Slavic epic song tradition. For the Homeric poems as a 'textile' I am indebted to the work of Gregory Nagy (see especially Nagy 2009). On the floral imagery and laments of the Iliad see Du' 2006: 62-70, with reference to Nagy 1979/1999 and Alexiou 1974/2002.

For Helen's perspective on the event's of the Iliad, see Ebbott 1999.

If you are interested in the ancient documents (Medieval manuscripts and ancient papyri) that transmit the Homeric poems from antiquity, see the Homer Multitext project [WEBSITE: The Homer Multitext: http://www.homermultitext.org]

Bibliography:

Alexiou, M. 1974/2002. The Ritual Lament in Greek Tradition. Cambridge. 2nd ed., ed. P. Roilos and D. Yatromanolakis. Lanham, MD.

Du', C. 2006. The Captive Woman's Lament in Greek Tragedy. Austin, TX.

Du', C. 2009. 'Epea Pteroenta: How We Came to Have Our Iliad.' In C. Du', ed., Recapturing A Homeric Legacy: Images and Insights from the Venetus A Manuscript of the Iliad. Cambridge, MA.

Ebbott, M. 1999. 'The Wrath of Helen: Self-Blame and Nemesis in the Iliad.' In M. Carlisle and O. Levaniouk, eds., Nine Essays on Homer (Lanham, MD, 1999): 3-20.

Lord, A.B. 1960 (2nd rev. edition, 2000). The Singer of Tales. Cambridge, MA.

Nagy, G. 1979/1999. The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry. Baltimore.

Nagy, G. 1996. Poetry as Performance. Cambridge.

Nagy, G. 2009. Homer the Classic. Cambridge, MA.

Parry, A., ed. 1971. The Making of Homeric Verse: The Collected Papers of Milman Parry. Oxford.

Pylos fresco image courtesy of the Center for Hellenic Studies.