Bike Variations

by Roger Kaza

Today, variations on a bicycle. The University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

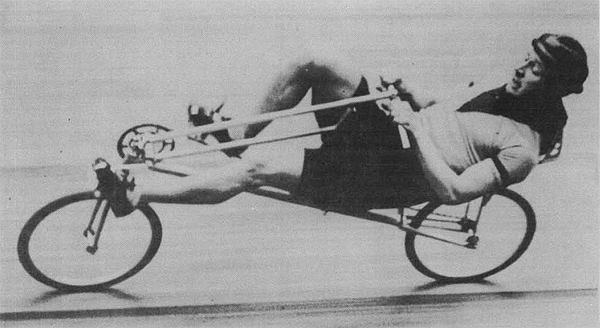

When is a bike not a bike? The French bicycle builder Charles Mochet must have wondered that in 1934. His bike and its rider had just set a new world record for distance traveled in an hour: 45 kilometers, or almost 28 miles. Mochet's bike had two wheels, pedals, a chain, and no added aerodynamic aids such as foils or the like. But, all the same, it looked very different from other bikes. It was much lower to the ground. Instead of sitting above the rear wheel, Mochet's rider slouched between the wheels as if on a chaise lounge. His feet were in front of him instead of below him. He was riding what we now call a recumbent bicycle.

The new record caused an uproar. At their very next meeting, the International Cyclist's Union, or UCI, debated the issue. After much discussion they decided, essentially, that Mochet's bike, well ... really wasn't a bike, as defined by them. The record was set aside.

But critics of the decision noted there might be some other factors at play. The UCI was heavily supported by manufacturers of conventional bikes. And the record-setting rider, Francis Faure, was a mere category 2 cyclist. He had now defeated some of the top riders in the world. Did the human set the record, or the machine?

Francis Faure riding Charles Mochet"s recumbent bike.

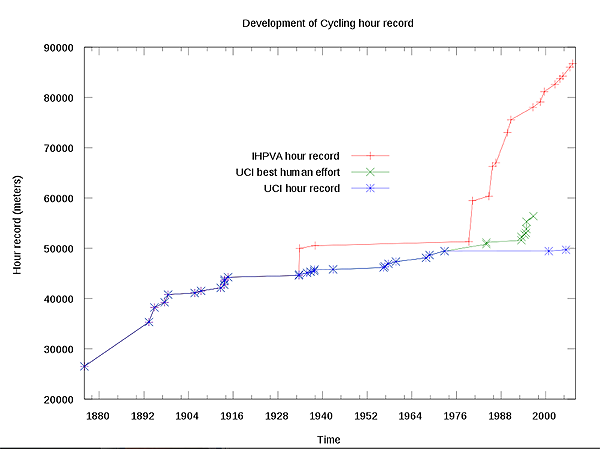

Today, with sophisticated wind tunnels, we can answer that pretty definitively. Faure almost certainly wasn't the world's fastest pedaler at the time. But in his low-slung bike, he had the laws of physics on his side. A cyclist traveling 25 miles an hour is expending something like 85% of his or her energy just overcoming wind resistance. Any small change in rider position, or in the profile of the bike, will make a huge difference. Recumbent bikes have less surface area facing the wind, so they're faster at high speeds. Fully enclosed bullet-shaped low-riders have now achieved astonishing results. The current one-hour record in a streamlined recumbent is 90 kilometers, vs. somewhere in the 50s for a normal racing bike.

Mochet appealed the ruling, but he lost, and so recumbents disappeared from races. In the 1970s, they started to make a comeback for recreational cyclists. In addition to being theoretically faster, they can also be more comfortable for some riders. I ride one myself. Go to any health club and you'll find a dozen of their stationary cousins parked in front of the TV. Recumbent pedal power has driven boats and even airplanes. Just don't expect to see one in the Tour de France any time soon.

Mochet appealed the ruling, but he lost, and so recumbents disappeared from races. In the 1970s, they started to make a comeback for recreational cyclists. In addition to being theoretically faster, they can also be more comfortable for some riders. I ride one myself. Go to any health club and you'll find a dozen of their stationary cousins parked in front of the TV. Recumbent pedal power has driven boats and even airplanes. Just don't expect to see one in the Tour de France any time soon.

To some degree it's an old story. Change the tools of the game, and you've changed the game. You can't blame competitive cycling for standardizing the racing bike — tradition, and previous records, count for a lot. But that means the only variable left to improve is the human machine. The recent doping scandals in cycling are a dark reminder of the lengths we will go to tweak that half of the equation. It makes one nostalgic for those innocent times when a lone tinkerer could take on the world in his whacky-looking bike.

I'm Roger Kaza, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

"The record was set aside." What happened was that the UCI appointed a special commission to rule on whether Mochet's bike was legal. Two months later, it came back with very precise definitions of a bike: height of bottom bracket from ground, distance from seat to pedals, etc. These dimensions effectively ruled out recumbents, including Mochet's bike. His record, which did hold for a brief two months, was assigned to an obscure new category, "special records set by machines without aerodynamic devices and propelled by human power." In other words, forgotten.

Wikipedia entry on recumbent bikes.

Engines No. 1468 covers the history of the bicycle.

Human Power Issue No. 38, Summer/Fall 1994, contains an interesting article on the Mochet bike. This is the official publication of the IHPVA (International Human Powered Vehicle Association.)

Mochet started his career making four-wheeled Velocars, intended for lower-income families who could not afford a motorized car. His racing bike was really, in effect, a "half-velocar." Mochet, did not, however, invent the concept of recumbent bikes. They have been around since at least the 1890s.

Mochet"s son George continued the family tradition of velocars until his death just two years ago (2008). Eventually Mochet made motorized microcars.

Remarkable short YouTube home video of Sam Whittingham in his streamliner. Whittingham holds the world human-powered land speed record, 82.33 mph (a flying start over a 200 meter course) as well as the current HPV hour record discussed below.

Wikipedia entry on the Hour Record. There are now three categories of records. The UCI (Union Cycliste Internationale) maintains two. One is simply called the "UCI" record, and mandates that to qualify, the rider must use bike equipment equivalent to that used by the legendary Eddy Merckx in 1972 when he set his hour record. The second category, "Best Human Effort" allows certain aerodynamic enhancements such as aero helmets or disc wheels on conventional bikes. The third category, maintained by the IHPVA and WHPVA, has no equipment restrictions of any kind, provided the vehicle is propelled solely by human power. The chart below plots the history of records in these three categories.

Photos in the public domain. Chart courtesy of Wiki Commons.