Edith Cavell

Today, Edith Cavell. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

"What's that mountain," we ask the bus driver in Jasper, Alberta. There it looms, eleven thousand feet high and marked with diagonal rock strata that glow pink in the morning and evening sun. "That," he tells us, "is Mount Edith Cavell."

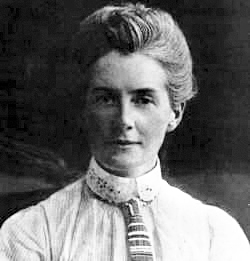

So we learn that Edith Cavell was born in a village near Norwich, England, in 1865 -- the daughter of an Anglican priest. She went on to become a governess, working in Belgium. Then, at the age of forty, she decided to take up the new field of nursing.

She trained in the Royal London Hospital and went back to Belgium. There, she was soon matron of the Berkendael Medical Institute -- a Belgian nursing school -- and a noted figure in the field. She even created a new nursing journal.

Cavell went on leave back in England in the summer of 1914. Just the n, the guns of August erupted. The Germans quickly overran Belgium. Yet Cavell, despite protests of friends and family, went back to her work under German occupation. She found herself treating allied soldiers. So she became part of an underground railway system to get them out of Belgium through neutral Holland. Soon she was smuggling unwounded soldiers as well.

n, the guns of August erupted. The Germans quickly overran Belgium. Yet Cavell, despite protests of friends and family, went back to her work under German occupation. She found herself treating allied soldiers. So she became part of an underground railway system to get them out of Belgium through neutral Holland. Soon she was smuggling unwounded soldiers as well.

Within the year, the Germans were on to her. The arrested her and held her incommunicado. She couldn't even talk to her lawyer. The charge was treason, and she refused to lie to save her own skin. She freely admitted smuggling 200 soldiers out.

The Americans put the most pressure on the Germans to show leniency. And the German civilian authority was inclined to do so. But the German military rushed to put her and a young Belgian architect, Philippe Baucq, before a firing squad. Just hours later, the Germans authorized the death penalty for her crimes.

The head American diplomat in Belgium had warned the Germans that that her execution would greatly hurt their cause. The sinking of the Lusitania had taken place three months earlier -- now this! He was right, of course. Edith Cavell became a martyr.

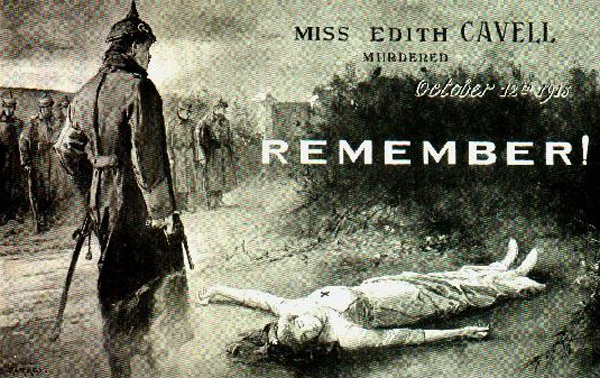

The press offered two versions of her story. One portrayed a young innocent who'd taken up spying on the Germans. The other was a sober woman who meant to do the right thing -- let the chips fall where they may. Both versions became wildly embroidered propaganda. That American diplomat was right: she became as big a rallying cry for America entering the war as the Lusitania sinking.

And yet, the night before her execution, she made her most famous remark: "I realize that patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone." That hardly matches the jingoism that followed her death.

Still, if anyone deserves her many monuments and memorials, Edith Cavell does. We find them in Trafalgar Square, in the Tuileres, in Brussels. But none are quite as dramatic as that huge mountain -- that great protective bulwark -- looming over the lovely little tourist town of faraway Jasper, Alberta.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

See the Wikepedia and The Great War Society sites for more on Edith Cavell.

Images: Edith Cavell and WW-I poster courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Mount Edith Cavell photo by J. Lienhard.

This propaganda photo reflects one of the myths that circulated about Cavell's death. It was that she'd refused a blindfold, that she'd fainted when she saw the firing squad, and that a German officer had cold-bloodedly shot her as she lay unconscious. In fact, she had been quite composed. She told a chaplain before she was shot, "I have seen death so often that it is not strange or fearful to me."