Amy Darlington's Book

Today, Amy's Book. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

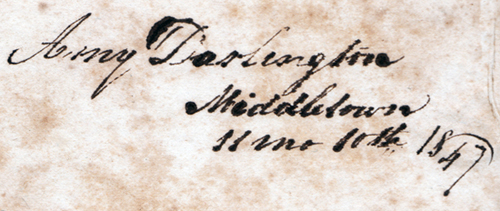

The signature in my copy of Denison Olmsted's Compendium of Natural Philosophy says, "Amy Darlington, Middletown, [Nov. 10th] 1847." It turns out that Amy Darlington is a given name. She's a 29-year-old widow living in Pennsylvania. Her husband, Emos Edwards, died six years earlier; and now she's studying physics.

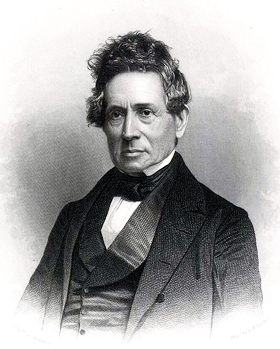

The book's author, Denison Olmsted, taught at Yale College. He pretty well covered the science waterfront, although he shied away from math. He was known for his work in geology and astronomy; and he held a patent for making illuminating gas from cotton seed. But Olmsted was primarily a teacher and a textbook writer.

The book's author, Denison Olmsted, taught at Yale College. He pretty well covered the science waterfront, although he shied away from math. He was known for his work in geology and astronomy; and he held a patent for making illuminating gas from cotton seed. But Olmsted was primarily a teacher and a textbook writer.

This is a late printing of a 20th-edition. It followed another very popular natural philosophy text by British author Jane Marcet. But, while Marcet wrote a dialog between a tutor and two pupils, Olmsted used a fleshed-out outline style. He lists bullet entries and explains each. Unlike Marcet, he dodges theory. When he deals with steam engines, for example, he says nothing about the fundamentals of heat and energy. I find Marcet's book more interesting. Still Olmstead is lucid and straightforward.

He is kin to Marcet in one feature. He saw very clearly that women were claiming access to a science education. One of his books was titled, Letters on Astronomy, Addressed to a Lady.The Preface to my copy of his natural philosophy book specifically says that this work should serve women and men alike.

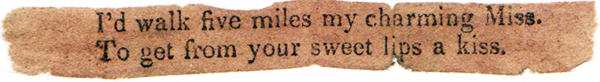

And so Amy Darlington reads it. But there's more to this story. As we read, we find something quite odd. Throughout the text, tiny slips of paper, rather like those in fortune cookies, turn up in the gutters between pages. They've turned brown with age and each has a printed couplet. Their greeting-card sentiments seem to reflect the text in the book. In the section on Lightning Rods we read,

I'm sure that you may plainly see

That you have captivated me.

Where Olmsted talks about compasses, we find:

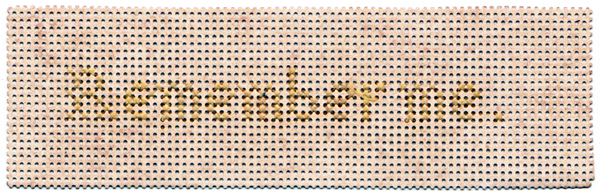

These little notes gain intensity when we take them as a whole. Then a real zinger pops up among them: In one gutter, we find a bit of cloth embroidered with the words "Remember me."

I've often said that, if the past held no secrets, there'd be no history -- only a dry record of facts. We're certainly driven to guess that a grieving Amy Darlington placed these notes. While we'll never fully understand this strange message in a bottle, we do know that Amy lived to the age of 92, and she never remarried.

Of course, this bottle contains a second message. And it's addressed to you and me: It is that the study of the world around us -- Olmstead's world of levers, siphons and circuits -- triggered someone's imagination so long ago. And that study of material reality still promises to unleash our own forces of imagination, today.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

D. Olmsted, Compendium of Natural Philosophy, Adapted to the Use of General Readers and of Schools and Academies ... (New Haven: S. Babcock, 1847). All images except the photo of Olmsted are from this source. The Olmsted photo is courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

For more on Olmsted, see the Wikipedia entry or this Documenting the American South article.

Amy Darlington Sharpless was born Jan 8, 1818 in Middletown Township, Delaware Co., PA. She was married briefly to Emos Edwards who died when they were both only 21. She died as Amy Darlington Edwards on Feb. 27, 1910, at the age of 92.

My thanks to Pat Bozeman, UH Library for providing biographical material on Amy Darlington Sharpless. Librarians from northern Delaware (the wrong Middletown) steered me to SDS's home in Middletown, PA. These include Mary McNeely, Alison Matson, and "Pam N."

Below is a list of inclusions in the book, and their placement:

pgs 144-5 Specific Gravity: That question, sir, in preference to the rest,/I mean to keep a secret in my breast.

pgs 148-49 Phenomena of Rivers: Tho' a kiss stop my breath, yet as willing am I/Than any, fair maiden, more kissing to try.

pgs 170-71 Mechanical Properties of Air: Ah me, you stole my heart, I fear,/I sigh so much when you are near.

pg. 189 The section on The Syphon is dog-eared.

pgs 210-211 The Reflection of Sound: You say you'd marry if you could,/She says I'll marry if you would. (this one is accompanied with a the stem of a plant)

pgs 236-37 Electrical Light: In kisses dear maid, can't we make a trade?/I'd be happy if you it would suit/I'd give two of mine for each one of thine,/And myself heart and hand to boot.

pgs 258-59 Lightning Rods: I'm sure that you may plainly see/That you have captivated me.

pgs. 284-85 The Compass: I'd walk five miles my charming Miss/To get from your sweet lips a kiss.

pgs 318-19 Vision: Here a small open meshed cloth embroidered with Remember me

pgs 320-21 Vision: The happiest moments that I see/Are those, dear Sir, I spend with thee.

pgs 334-35 Microscopes: Bachelor, repent, 'tis time to take a wife,/Your happiness forbids a single life.

pgs 374-75 Select Experiments: If you could fancy me, why then/I'd be the happiest of men.

pgs 414-15 Select Experiments: I send this, Sir in hopes to please,/And set my tender heart at ease.

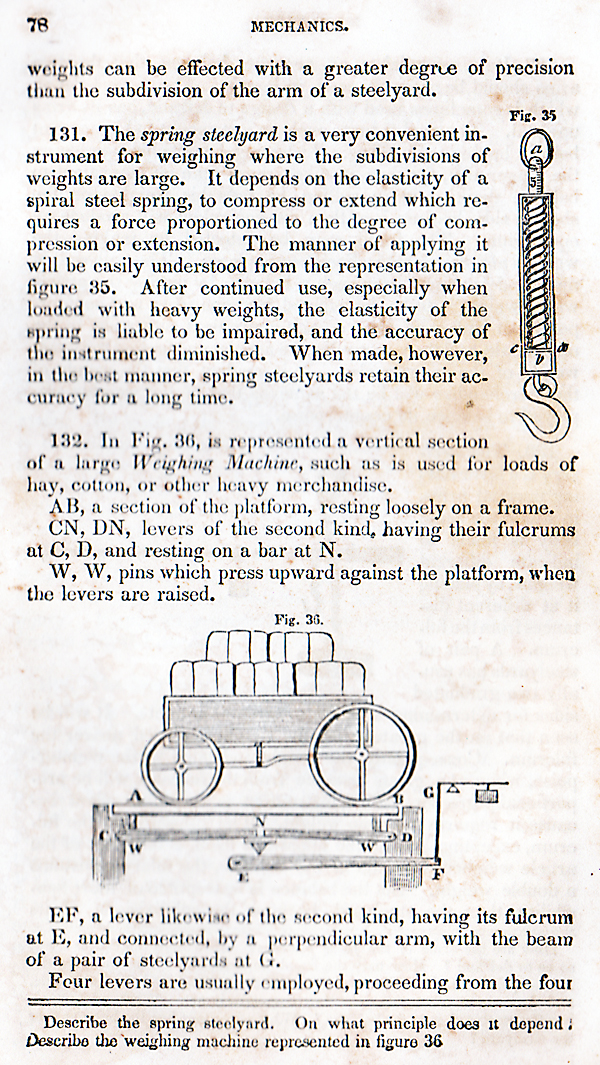

A typical page of Olmsted's textbook. He leaned toward very realistic and practical illustrations.