τέχνη, Tacit & Spoken

by Helen Valier

Today, medical historian Helen Valier offers us a new look at the language of technology. The University of Houston's Honors College presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

What are we really talking about when we talk about technology? At first glance the answer to this question seems obvious, but maybe not.

Take for example a bicycle and a novice rider. How are we to teach our novice how to ride? Should we leave him with the bike and a list of written instructions? Then he can figure out this whole riding thing for himself. Surely if we know everything there is to know about riding a bike then we can just write out our instructions and pass them on, right?

Take for example a bicycle and a novice rider. How are we to teach our novice how to ride? Should we leave him with the bike and a list of written instructions? Then he can figure out this whole riding thing for himself. Surely if we know everything there is to know about riding a bike then we can just write out our instructions and pass them on, right?

Wrong, of course! Our novice first needs to observe the spectacle of bike riding. Then he needs to try to manipulate the machine for himself. As we observe his wobbly progress we can offer advice.

As a result of these interactions our novice rider undergoes a transformation. He has learned a skill. Our cyclist has gained expertise and mastery through verbal instruction and practical experience.

The Ancient Greeks, despite not having bicycles, were well acquainted with this phenomenon. In fact, it is from the Greek word — τέχνη (or techne) — meaning the art or the skill of doing that we derive the word 'technology'. Some modern philosophers argue that all technology retains something of this ancient techne.

The French philosopher Michel Callon imagines us taking a technology and writing all the instructions about using it in red. He then asks us to somehow convey all the skill involved in using it in green. A visiting Martian contemplating our science would see our knowledge base as a vast sea of green, punctuated only occasionally by a fragile filament of red.

Callon asks us to understand that much of the knowledge that makes up our world is unspoken. We communicate this tacit knowledge through interaction with the material world. Using technologies are part of what makes us human. And how we choose which technologies to make our own is similarly deeply grounded in our human culture and values.

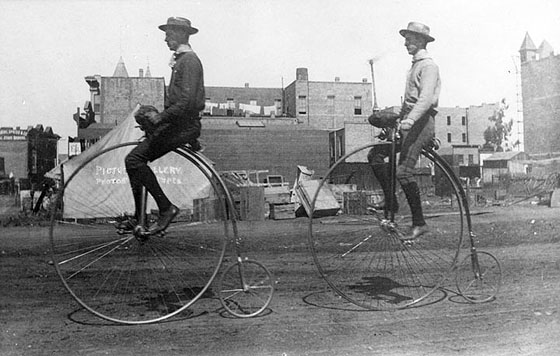

In the 19th century young men, addicted to speed, chose the high-wheel 'Penny Farthing' bicycle over safer (and to our eyes, more modern) low riding designs. With these bicycles came great speed but also horrible injury! As the bicycle became a more routine part of urban transportation, the high wheel design died away.

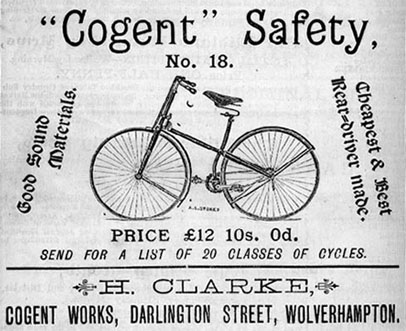

By the 20th century, the many different bicycle designs had coalesced into our basic safety chain form with usually only minor variations. Bad luck for our thrill-seekers, but a practical design to suit most riders.

So the next time you introduce a thrill-seeking youngster to a bicycle stop and remember a little of this history. Know too that you are about to observe an ageless dance between the social and the material worlds. In this age of high technology we must still all be artists.

I'm Helen Valier, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

M. Callon, 'Is Science a Public Good?' Science, Technology & Human Values, 19 (1994).

For more on bicycles and human values: W. Bijker. Of Bicycles, Bakelites, and Bulbs: Toward a Theory of Sociotechnical Change. Boston: MIT Press, 1997.

All images are from Wikimedia Commons.

Helen K. Valier (BA, University of Cambridge, MSc., Ph.D., University of Manchester, UK) is an historian of medicine and an Instructional Assistant Professor with the Department of History and The Honors College at the University of Houston. As coordinator for the Medicine & Society Program at Houston, she creates curricula for undergraduate students wishing to study the history, ethics and politics of medicine and healthcare. Her first book (co-authored with J.V. Pickstone) Community, Professions and Business (Manchester NHS Trust, 2008) was a study of the UK National Health Service in Manchester, England, across half a century. She is currently writing a book on the comparative history of clinical trials in cancer therapy in the UK and USA.