Houston and the Railways

Today, a 4-4-0 locomotive -- in the wrong place. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The Great Seal of the City of Houston may not seem surprising at first glance. It shows an early locomotive, which makes perfect sense. Houston is America's second largest port, and rail carries much of the freight -- coming and going. But that seal was adopted in 1840. Rail was scarcely ten years old in America. No locomotive had yet been anywhere near Houston, nor was Houston a seaport. It's fifty miles inland from the deep-water port of Galveston.

The Great Seal of the City of Houston may not seem surprising at first glance. It shows an early locomotive, which makes perfect sense. Houston is America's second largest port, and rail carries much of the freight -- coming and going. But that seal was adopted in 1840. Rail was scarcely ten years old in America. No locomotive had yet been anywhere near Houston, nor was Houston a seaport. It's fifty miles inland from the deep-water port of Galveston.

Douglas Weiskopf begins his book, Rails Around Houston, with this strange state of affairs. He suggests the seal reflected masterful hucksterism -- and vision. Houston came into being when the Allen brothers, John and Augustus, came to the new Republic of Texas in 1836. They bought up ten square miles of land adjacent to Harrisburg, Texas, and set out to form a major city on Buffalo Bayou.

A year later, the city became temporary capital of the Republic, it took the name of its hero Sam Houston, and the riverboat Laura made the first trip up the Bayou from Galveston. The Allens had meant to make Houston the region's "great commercial emporium," and that process had already begun. Buffalo Bayou now served as the watercourse for Galveston's goods, but where did one go from there?

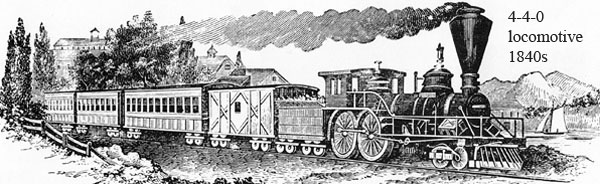

Rail would have to be answer and rail was hardly invented; so we're back to Houston's seal with its remarkably modern locomotive -- what's called a 4-4-0. That meant four small idler wheels in front to steer it around bends, four large wheels driven by the steam engine, and no idler wheels behind.

The 4-4-0 was a distinctly American design. Henry Campbell of Philadelphia had just received a patent for it four years earlier. It was still in development. Once honed, that design would dominate 19th century rail service and last well into the 20th century. It became known as the American type of locomotive.

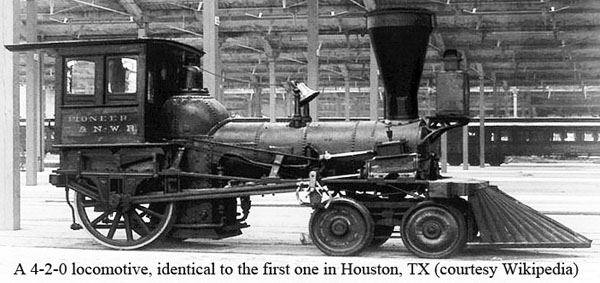

But it took be another twelve years after that seal design for Houston to get any locomotive at all. In 1852 the embryonic Buffalo Bayou, Brazos, and Colorado Railway bought a second-hand 4-2-0 engine, much more primitive than the one on the seal. (The president of the railroad made the dubious boast that it could do 35 miles-an-hour.)

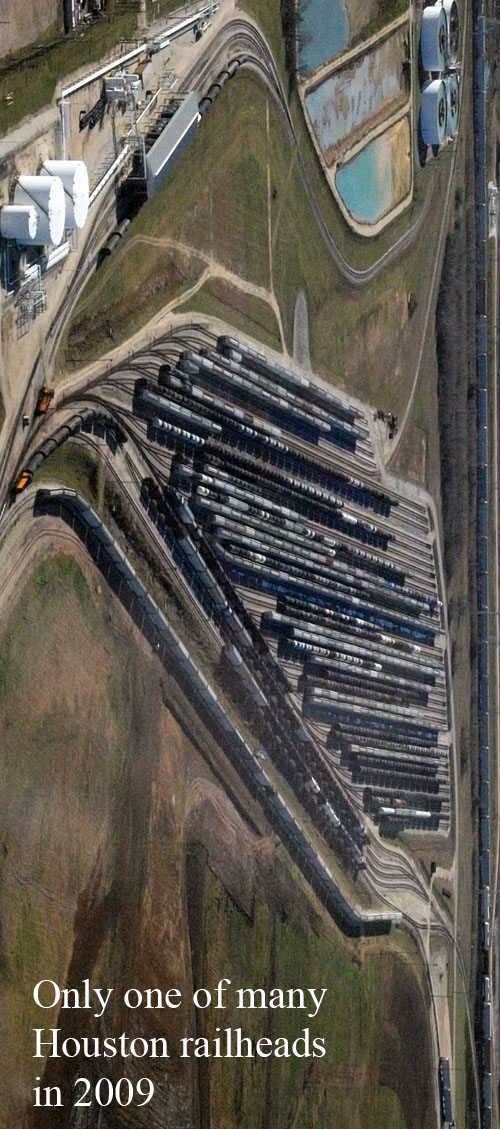

Another two years passed and a third engine -- a 4-4-0 -- was added. Our railway finally had a locomotive like the one that dreamers had put on the city seal 14 years before it. The Allen brothers' dream was in motion, but what about them? John died even before the seal was designed, and Augustus died just after the Civil War. Neither lived to see Buffalo Bayou dredged to form a ship channel all the way into Houston. Neither saw six thousand miles of track being laid in Texas during the 1880s.

But then again, maybe they did. Maybe those two brothers, still in their twenties, somehow saw it all, way back in 1836 -- saw a great city when it was nothing but flat, hot, inhospitable expanse, stretching off to infinity in every direction.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

D. L. Weiskopf, Images of Rail: Rails Around Houston. (Chicago: Arcadia Publishing, 2009). See also the Wikipedia articles on 4-4-0 and 4-2-0 locomotives and web articles on the history of Houston, on the history of Harrisburg, on Augustus Chapman Allen, and on John Kirby Allen

Harrisburg, Texas, was the original port town on Buffalo Bayou. Houston gradually engulfed it and, in 1926, with a population of only 1460, it was annexed by Houston. Today it still exists as a community on the east side of the city.

Photo by J. Lienhard