Nostrums and Quackery

Today, quack medicine. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Here's a 1912 edition of Nostrums and Quackery: Articles on the Nostrum Evil, Quackery and Allied Matters Affecting the Public Health edited by one Dr. Arthur J. Cramp. Cramp had lost a daughter to quack medical treatment and he meant to rid the world of those parasites. This is no scattershot attack; it's a carefully documented steamroller, backed by the AMA and much of it based on their material.

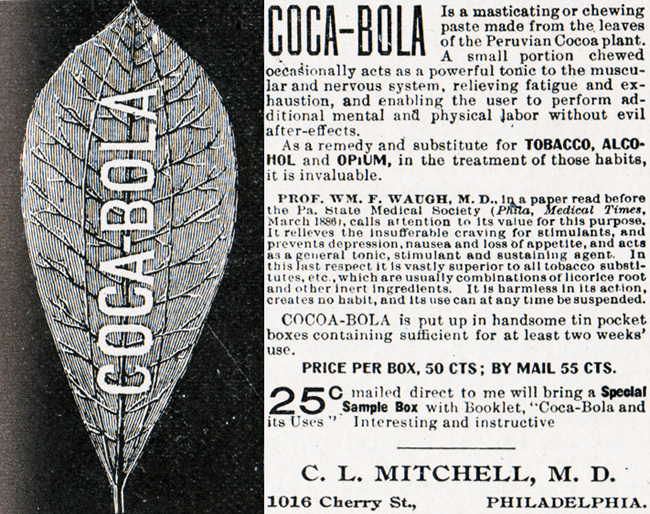

Snake oil salesmen have been around as long as we've had ailments. But two forces drove their mischief to a fever pitch in the late 19th century. The invention of really fast printing presses provided criminals with new access to the public (a lot like our Internet with its floods of SPAM.) Cramp's first chapter details the advertising tactics used by this new generation of con artists.

Snake oil salesmen have been around as long as we've had ailments. But two forces drove their mischief to a fever pitch in the late 19th century. The invention of really fast printing presses provided criminals with new access to the public (a lot like our Internet with its floods of SPAM.) Cramp's first chapter details the advertising tactics used by this new generation of con artists.

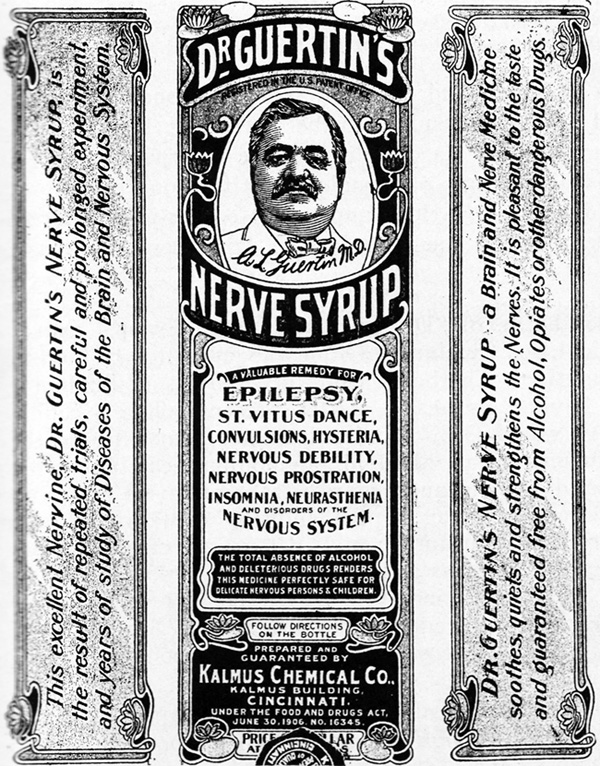

The other factor was the rise of "scientific" medicine -- medicine based on new chemistry, new instruments, and a general sense that panacea cures of every kind were just around the corner. An expectation of medical miracles left everyone vulnerable. Cramp begins by explaining how they advertised. He warns, for example, that venereal disease sufferers, desperate for secrecy, are often subjected to methods bordering on extortion. Then he devotes chapters to disease-specific scams, cures for cancer, consumption, "female weakness", epilepsy, obesity, addiction, baldness, croup.

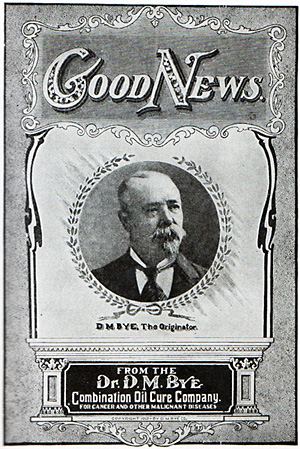

The quacks offer feel-good tonics for internal cancers, and caustic poultices for external growths. They sell laudanum-laced tonics to soothe babies. For consumption (or tuberculosis) they rely heavily on testimonials and photos of sage-looking doctors to promote their mail-order nostrums. The testimonials were usually as fake as the doctor's credentials. One investigator managed to trace 39 patients of a particular consumption institute. He found 36 had died and two were dying.

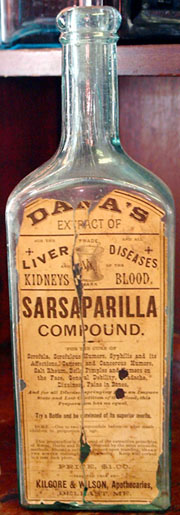

Cramp reports chemical analyses of the typical elixirs. The ingredients are repetitive: water, a lot of alcohol, maybe some flour, a dash of strychnine, perhaps a zinc compound or a dollop of castor oil -- and some added odor or coloring.

Cramp reports chemical analyses of the typical elixirs. The ingredients are repetitive: water, a lot of alcohol, maybe some flour, a dash of strychnine, perhaps a zinc compound or a dollop of castor oil -- and some added odor or coloring.

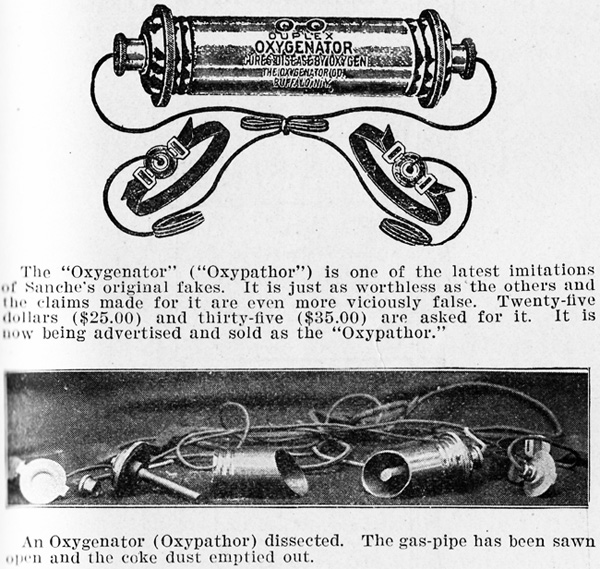

I was especially taken by the mechanical gadgets. (It's no trick to make a machine that looks powerful and potent; sci-Fi movie-makers do that all the time.) When you strapped on Sanche's Oxygenator, your body was supposed to take up oxygen and heal itself of any disease. Big market there! It was no more than an engraved tube filled with coke dust, and fitted with tubes and straps.

And yet Dr. Cramp's array of electromechanical quackery anticipated real machines in your doctor's office today. That's the cruelest part of this book. All this fakery anticipated the pills and machines that really would, one day, alleviate pain and disease. No wonder we were so gullible a century ago. Those charlatans all promised the world we now live in. If only it'd been just science fiction -- it might've been something we could admire today.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Nostrums and Quackery: Articles on the Nostrum Evil, Quackery and Allied Matters Affecting the Public Health; Reprinted, With or Without Modifications, from The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2nd ed., ed.: A. J. Camp, (Chicago: AMA Press, 1912). A 2nd Volume was published in 1921 and a 3rd added in 1936. By 1936 the tone of both ads and the criticisms are toned down. Now we find things like critical evaluations of Alka-Seltzer and Sal Hepatica.

For an excellent account of the rise of technological medicine (which was both a stimulus for much of this flurry of quack medicine and its death knell as well) see S. J. Reiser, Technological Medicine: the Changing World of Doctors and Patients. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

See also a recent account of quackery in this period: B. McCoy, Quack! Tales of Medical Fraud. (Santa Monica Press, 2000.) Listeners in the Houston area might enjoy visiting the 20th Century Technology Museum, Wharton, TX. It has a nice collection of bogus devices, especially various electrical healing gadgets. B&W images are from Cramp's books; sarsaparilla photo is by J. Lienhard.

The active ingredient in Coca Bola was cocaine.