Powering Aeroplanes

Today, we wonder how to power our flying machines. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Think about how we use power to carry us into the sky. The Wright Brothers looked at that problem and chose to pull an airfoil-shaped wing through the air with a propeller. We take that for granted today -- sometimes replacing the propeller with a jet. Yet the Wright's choice was not cast in stone back then.

Think about how we use power to carry us into the sky. The Wright Brothers looked at that problem and chose to pull an airfoil-shaped wing through the air with a propeller. We take that for granted today -- sometimes replacing the propeller with a jet. Yet the Wright's choice was not cast in stone back then.

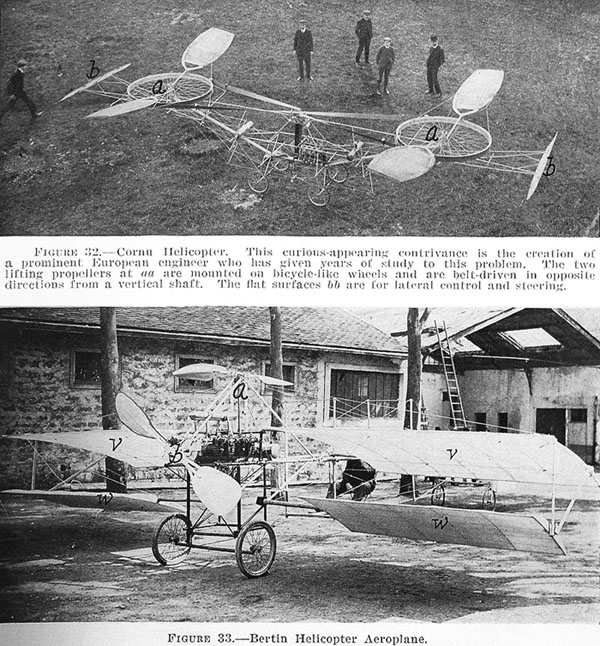

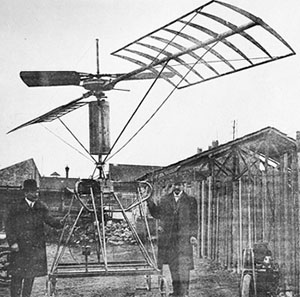

Would-be airplane makers were still seriously weighing two other options in 1903. Inventors, ever since Leonardo, had known that helicopters could be made to work. The wing could be eliminated and the airplane lifted by a large upward-facing propeller.

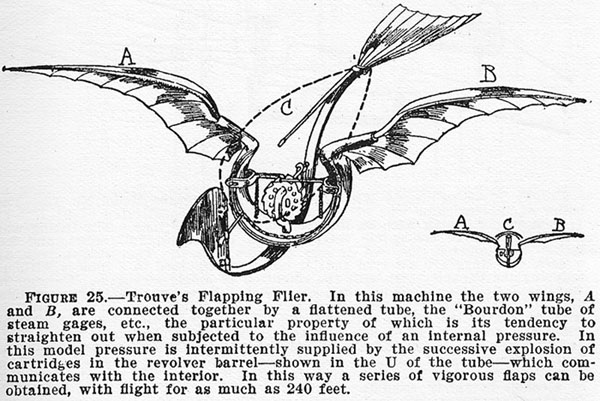

The even-more-obvious form of propulsion was the one used by birds -- no propellers, no jets. Birds simply apply power directly to their wings. A machine that does that is called an ornithopter -- something we have yet to master. Ornithopters have flown, but only marginally -- we have not caught up with birds. Then there's the autogiro. A propeller pulls it forward, but, instead of a wing, a large horizontal motorless propeller windmills above it. It is what lifts an autogiro into the sky.

Of course, endless variations can be played on that theme of lift and propulsion. And I understand that much better now that I've read Victor Lougheed's 1910 treatise on flight. Lougheed was first to write comprehensively on designing and building flying machines. Early on, he devotes sixteen pages to ornithopters and helicopters.

Two centuries ago, one Joseph Degan reportedly flapped himself up to a height of 54 feet in an ornithopter. Lougheed tells of many other contemporary builders trying to make such machines work.

Two centuries ago, one Joseph Degan reportedly flapped himself up to a height of 54 feet in an ornithopter. Lougheed tells of many other contemporary builders trying to make such machines work.

When it came to helicopters, Lougheed described four -- one that's been forgotten, and three that actually flew. French bicycle-maker Paul Cornu built a helicopter that rose several feet off the ground and stayed aloft for nearly a minute. The Bréguet brothers built one that got a foot or so off the ground. And Emile Berliner, best-known for inventing the disc phonograph, was just beginning work on one. His actually flew rather well in the 1920s. The German Focke-Wolfe Company, and Igor Sikorski in America, finally made really successful helicopters in the late 1930s.

When it came to helicopters, Lougheed described four -- one that's been forgotten, and three that actually flew. French bicycle-maker Paul Cornu built a helicopter that rose several feet off the ground and stayed aloft for nearly a minute. The Bréguet brothers built one that got a foot or so off the ground. And Emile Berliner, best-known for inventing the disc phonograph, was just beginning work on one. His actually flew rather well in the 1920s. The German Focke-Wolfe Company, and Igor Sikorski in America, finally made really successful helicopters in the late 1930s.

The primacy of the propeller-driven aeroplane was far from settled a century ago, nor were other technologies. Steam and electric automobiles hadn't yet yielded to gasoline. Now electric cars are back; and steam cars could also rise again. Similar struggles go on all around us today. How, for example, will we ultimately store digital data? How will we do our distance communication? What energy sources will fuel our homes?

And -- will we one day fly in ornithopter aeroplanes after all? Lienhard's first principle of invention says that, if it can be made to work, it will be made to work. That's why I expect we really will, one day, fly in airplanes that flap their wings like hawks or humming birds.

And -- will we one day fly in ornithopter aeroplanes after all? Lienhard's first principle of invention says that, if it can be made to work, it will be made to work. That's why I expect we really will, one day, fly in airplanes that flap their wings like hawks or humming birds.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

V. Lougheed, Vehicles of the Air: A Popular Exposition of Modern Aeronautics with Working Drawings. (Chicago: The Reilly and Britton Co. 1909/1910). My thanks to Robert Wells for my copy of Lougheed's book. All black and white images from this source. Bird photos by J. Lienhard.