Battle of the Restigouche

Today, the last naval battle of The Seven Years War. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

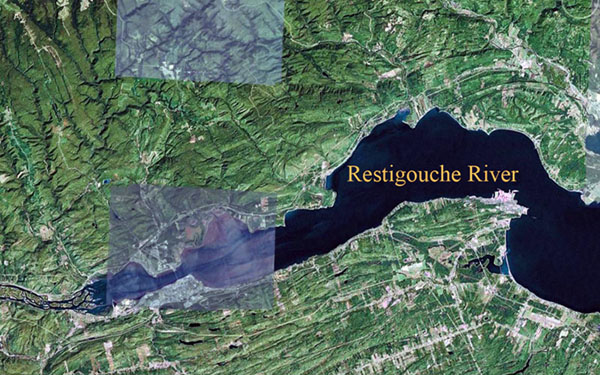

To the north of Canada's Gaspé Peninsula is the St. Lawrence Seaway, the old Northwest Passage to the Great Lakes region, the route used by French explorers and settlers since the early 16th century. To the south is the smaller Restigouche River. When The Seven Years Warbegan, in 1756, the Restigouche valley was home to some French Acadian settlements, but it primarily remained part of the Mi'kmaq Indian nation.

We in America call that war, The French and Indian War, but it was a much larger conflict -- a worldwide political realignment that touched all Europe as well as America. In North America, it was the British against the French and their Native American allies over control of Canada as well as much of what would later be part of the US.

It began badly for the British. The French beat George Washington in Pennsylvania, and the British suffered serious losses in upstate New York. It began turning against the French at the New York forts of Ticonderoga and Niagara. And 1760 found the British in control of Quebec City on the St. Lawrence -- but only barely.

They were hungry and under siege, so they left the city to fight the French in the field. There they suffered their bloodiest loss of the war and had to retreat back into the city. Maybe France really would win control of Canada after all.

But the French were also starving. They desperately awaited resupply ships from France. With supplies, they might yet regain the upper hand. Part of a relief convoy from France was lost to a British naval blockade. Then the remaining three French ships found the British blockading the mouth of the St. Lawrence. They managed to capture some of the smaller British ships. Then they retreated to up in the Restigouche River to get fresh provisions from the Acadians and to get support from several smaller Acadian vessels.

But the French were also starving. They desperately awaited resupply ships from France. With supplies, they might yet regain the upper hand. Part of a relief convoy from France was lost to a British naval blockade. Then the remaining three French ships found the British blockading the mouth of the St. Lawrence. They managed to capture some of the smaller British ships. Then they retreated to up in the Restigouche River to get fresh provisions from the Acadians and to get support from several smaller Acadian vessels.

But the British found them and bottled them in. For 17 days those two small fleets sparred. Finally the French had to scuttle most of their ships to avoid capture. But they had British prisoners in the hold of one large ship, so they simply abandoned it, warning the prisoners that the Mi'kmaqs would scalp them if they made it to shore. One of the prisoners managed to swim to a nearby British ship for help. It sent its longboats to that last French vessel, rescued the prisoners, then sank it as well.

And, with that, the Battle of Restigouche was over. French supplies were at the bottom of the river, and the French would formally surrender in Montreal a few months later.

Now a National Historic Site at Pointe-a-la-croix on the Restigouche River displays remains from the sunken fleet. Here in the Gaspé world of forests, birds, and bucolic beauty, is that remote corner of the world where the course of our Western Hemisphere was permanently reshaped. This was one of history's horseshoe nails -- a place where a small forgotten event changed everything for you and me.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J. Beattie and B. Pothier, The Battle of the Restigouche, 1760. (Ottawa: Minister of the Department of Canadian Heritage, 1996).

See the Wikipedia sites for The Battle of the Restigouche and The Seven Years War. le Machault image is in the public domain. Aerial photos courtesy of Google Earth