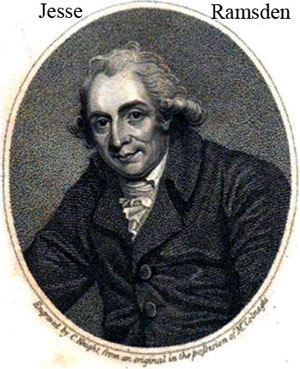

Jesse Ramsden

Today, Jesse Ramsden. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

One day, in the late eighteenth century, Jesse Ramsden went down to the palace of King George III in Kew Gardens. He wasn't expected; he had to talk his way in. He finally got his audience and was graciously received. Then he presented the King with a scientific instrument that he'd built on order -- maybe a sextant or a telescope, I don't know. The King admired it, then said,

I have been told, Mr. Ramsden, that you are ... the least punctual of any man in England; you have brought home this instrument on the very day ... appointed. You have mistaken only the year.

For the King to let Ramsden off with so gentle a scolding says volumes about Ramsden's stature as an instrument maker.

Compared with other monarchs of his time, King George live d a pretty simple and monogamous life. He was also a devoted student of science and agriculture, seriously interested in the latest scientific tools. That's why he hired Jesse Ramsden to build his instruments.

d a pretty simple and monogamous life. He was also a devoted student of science and agriculture, seriously interested in the latest scientific tools. That's why he hired Jesse Ramsden to build his instruments.

Ramsden, born in Yorkshire in 1735, apprenticed as a clothworker and he began in that business. But his growing fascination with scientific devices led him to begin a new apprenticeship as a maker of mathematical instruments at the age of 21. That was old for an apprentice. But he excelled and was soon running his own business.

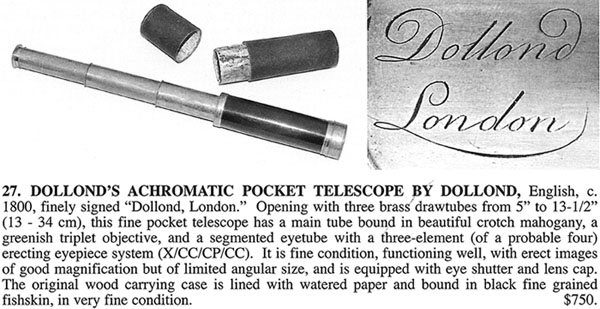

He also found a welcome in the wealthy family of John Dollond. Dollond held the first patent for an achromatic lens. Previous lenses all suffered from chromatic aberration -- rainbow fringes of light around the edges of objects. You and I were bothered by that in our early digital cameras. That's because lenses refract each color differently. Each color has a slightly different focus.

The first solution, invented by others but patented by Dollond, was to put a second lens with different refractive properties next to the first. Ramsden went on to use and improve that delicate technology. (He also married Dollond's daughter, Sarah.)

Yet lenses were only a fraction of all he made. He built circle dividers, sextants, balances, protractors, slide rules, transits, barometers ... He had a staff of some fifty workers, and his quality control seemed to surpass sanity. He was famous for missing deadlines. He drove clients (like King George) to distraction. Small wonder that, when he died in 1800, Dollond family executors could recoup only a tiny fraction of all the money owed him.

Ramsden exemplified a conviction that lay behind the Age of Enlightenment -- that all understanding flowed from precise measurement. Later science would turn to statistical inference, probabilistic analysis -- and ultimately quantum physics which would take us quite beyond measurement's reach.

Ramsden exemplified a conviction that lay behind the Age of Enlightenment -- that all understanding flowed from precise measurement. Later science would turn to statistical inference, probabilistic analysis -- and ultimately quantum physics which would take us quite beyond measurement's reach.

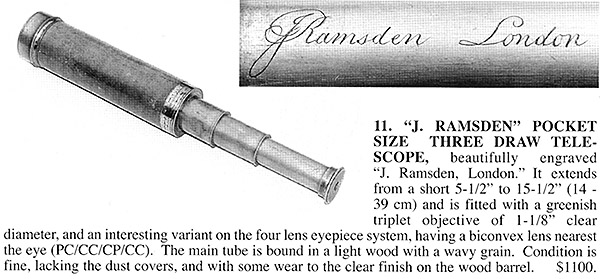

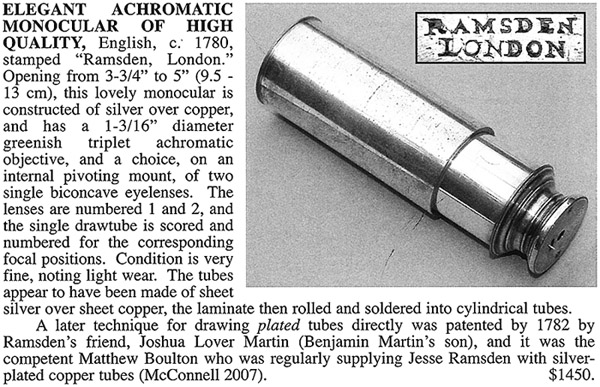

But now I hold an antiquarian catalog of Ramsden's instruments -- all masterpieces of hand-etching in brass and steel. And I smile the smug Enlightenment smile-of-reason at King George's year-long wait -- while Ramsden brought his instrument as close to perfection as one might approach, without offending his own Maker.

But now I hold an antiquarian catalog of Ramsden's instruments -- all masterpieces of hand-etching in brass and steel. And I smile the smug Enlightenment smile-of-reason at King George's year-long wait -- while Ramsden brought his instrument as close to perfection as one might approach, without offending his own Maker.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

A. Chapman, Ramsden, Jesse (1735-1800), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Vol. ?, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004): pp. 963-966.

The image of Ramsden is courtesy of Wikipedia Commons. All other images are from Tesseract: Early Scientific Instruments catalogs, Issues 86 and 87, Winter 2008/2009 and Spring 2009. (Co-published with Rittenhouse: the Journal of the American Scientific Instrument Enterprise.)

See also the Wikipedia entries on Jesse Ramsden, King George III, John Dolland, chromatic aberration, and achromatic lenses.