Antoine de St. Exupéry

Today, Antoine de St. Exupéry. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Antoine de St. Exupéry was born in France, in 1900. He studied architecture, then joined the Army just after WW-I. There he learned to fly. After that, he tried office jobs in Paris. And he began to write. In 1926, two things happened: he published his first story, The Aviator, and he returned to flying.

He flew in an embryonic airmail service between Toulouse, France, and Dakar, Africa. Two years later, he was in charge of a small airport in the Sahara desert. In that remote outpost he began writing novels. From then 'til his disappearance during a flight from Sardinia in WW-II St. Exupéry flew and he wrote.

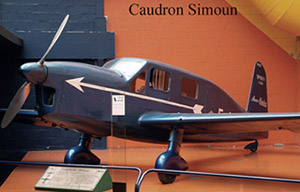

He flew airmail in Argentina and over the Andes. He flew out of Casablanca. He set out to win a prize for the fastest flight from Paris to Saigon, in 1935. But he crashed his Caudron Simoun in the Sahara. He wandered for days before a caravan rescued him.

He flew airmail in Argentina and over the Andes. He flew out of Casablanca. He set out to win a prize for the fastest flight from Paris to Saigon, in 1935. But he crashed his Caudron Simoun in the Sahara. He wandered for days before a caravan rescued him.

He escaped to America after Germany invaded France. Then, no longer young, he returned to fly with the Free French in the Mediterranean. His first flight had been in a Sopwith biplane. His last was in a Lockheed Lightning -- a P-38. Lost at sea, it wasn't discovered until the year 2000 when a diver located it near Marseilles.

All that was a career in itself. But while St. Exupéry is famous, it's not for flying but for writing. his last and most famous book was that masterpiece of children's literature The Little Prince. It was published during WW-II.

All that was a career in itself. But while St. Exupéry is famous, it's not for flying but for writing. his last and most famous book was that masterpiece of children's literature The Little Prince. It was published during WW-II.

His friend, the great André Gide, celebrated his writing, especially his writings on flight. Twelve years before The Little Prince, Gide wrote the forward to St. Exupéry's book, Night Flight. It leads us into the physical and moral rearrangements of aerial perspective. He writes of two peasants in a hut below his thrumming aeroplane:

They think ... their lamp shines only for the little table; but from fifty miles away, one felt the summons of their light, [like] a desperate signal from some lonely island, flashed by shipwrecked men toward the sea.

Gide wants us to know how grounded in existential reality all this is. He quotes from a letter St. Exupéry had sent him. St. Exupéry had just pulled off a dangerous exploit and said he now knew why Plato ranked courage last among the virtues. He called it,

Gide wants us to know how grounded in existential reality all this is. He quotes from a letter St. Exupéry had sent him. St. Exupéry had just pulled off a dangerous exploit and said he now knew why Plato ranked courage last among the virtues. He called it,

A touch of anger, a spice of vanity, a lot of obstinacy and a tawdry sporting thrill ... Rather a pleasant feeling, but ... another feeling creeps in -- of having done something immensely silly. I shall never again admire a merely brave man.

Many pilots wrote, many wonderfully well. But none wove the terrors and magic of early flight so compellingly. No new technology survives on function alone. It also needs a metaphorical place in our existence. By shaping such a place for flight, St. Exupéry literally helped to complete the invention of the aeroplane. I doubt we ever could've fully adopted so strange a machine without first having words, like his, to go along with it.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

See any of the vast number of publications of St. Exupéry's books, especially Night Flight(with Gide's introduction) and The Little Prince.

See the Wikipedia articles on St. Exupéry, Andre Gide, Night Flight, and The Little Prince. All images are courtesy of Wikipedia Commons.

See also the New York Times article on the discovery of St. Exupéry's P-38.

A P-38, the Lockheed Lightning, last plane St. Exupéry flew.