Sneaky Solar Energy

Today, a silent arrival. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Today's New York Times Science section had yet another article on energy being taken from wave motion. We've heard a lot about schemes for taking energy from ocean waves. World energy consumption is around sixteen terawatts at this writing -- that's sixteen thousand gigawatts. Ocean waves might have the potential for supplying a tenth of that. But the equipment would be huge, and we're also unsure of the environmental risks of big wave energy systems.

Now the article suggests another way this form of solar energy can be used. Two California engineers have made a small unmanned whale-monitoring device that travels the ocean. The monitoring equipment on the surface is linked by cables to a submerged platform, 20 feet down. The monitor functions are powered by solar panels. And, as the monitor bobs up and down, the cables work a mechanism below that propels it through the water at the speed of a walk.

In this case, wave power isn't used to generate power for sale -- only to give the monitor mobility. I think of the image of a lone railroad depot in an old western movie. Remember the large water tank for resupplying steam locomotives, and the large windmill that pumped water into the tank. A steam engine would've powered those pumps in a late-19th-century city. But, off on the prairies, a windmill needed neither fuel nor heavy maintenance.

Stand-alone systems like the windmill (or that whale monitor) are pretty common. Farm windmills still serve cattle-watering troughs. In the city, stand-alone solar panels are taking up many functions where they can't be put out of service by power outages. School-zone warning lights, widely powered by solar panels, are one example. Solar powered domestic alarm systems are another.

Our technologies so often start out in one form, only to be diverted into another. So-called green energy is a case in point. Certain applications are best served by large central power plants -- whether the power source is a windmill farm or a coal-fired steam generator. It's a lot more efficient to produce power -- or most anything else -- in bulk. So all the moral and economic arguments rage over the source of large-scale power. But green energy has already won the argument when it comes to energy in isolation. We argue over the efficacy of building huge wind farms, large solar towers, or many square miles of wave energy collectors, while these technologies actually enter beneath our radar -- on little cat feet.

They spring up in isolation, picking up independent tasks. Heating one house, electrifying an Aleutian village, doing this job and that within our cities. As this happens, the technology of these systems matures. While we argue about creating major installations, the technologies grow and evolve on the small scale. They enter our lives from the grass roots up. We gradually see more and more green energy systems. And, one day, before we've actually decided to adopt them, we'll wonder how we ever did without them.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

T. Walker, Wave-Powered Monitor Is Moving Beyond Listening to Whales. The New York Times, Science Times, February 24, 2009, pg. D3.

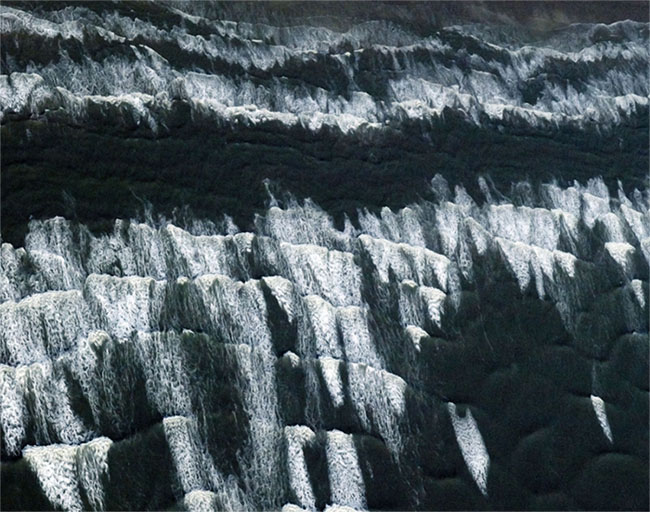

Overhead view of waves reaching Galveston Island. The shore is the top edge of the picture with the waves moving bottom to top. Photo by J. Lienhard with special thanks to pilot Bob Hawley.