Rachmaninoff Unblocked

by Roger Kaza

Today, a composer unblocked. The University of Houston's Music School presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Have you ever wondered why they call it "writer's block?" After all, non-writers get stumped and blocked from time to time, in whatever work they do. But writers get to name things, and, true to form, they named this universal affliction after themselves. That got me thinking about the composer Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Rachmaninoff reminds us that there really are two kinds of writer's block. One is saying you don't have any good ideas. Another is decreeing that the good ideas you have aren't good enough.

Now you can't blame Rachmaninoff for feeling this way. He'd been utterly savaged by the critics after the 1897 premier of his first symphony. One reviewer compared it to the ten plagues of Egypt, and suggested its composer had studied at a "conservatory in Hell." Those weren't exactly words of encouragement. Rachmaninoff was already a moody, intensely self-critical personality.

So it sent him into a deep funk. Maybe he would come out of it on his own. Or maybe he would just become a pianist. But his concerned relatives came up with a more proactive course of action: they sent him to see a hypnotist. Enter Dr. Nicholas Dahl.

Dahl was a physician with training in neurology. We don't know exactly what he and Rachmaninoff did, but we do know that in early 1900, they met daily for four months. Hypnotism had by then broken free of its peculiar, almost cultic beginnings and was finally becoming accepted as a powerful therapeutic tool. Even Dahl's contemporary Sigmund Freud practiced it for a time. But Freud hypnotized his patients to provoke a catharsis, which he believed would purge the psyche of long-repressed trauma. Dr. Dahl's approach we would recognize as considerably more modern. It was pretty much a pep talk. "You will begin to write your concerto," he told Rachmaninoff. "You will work with the greatest of ease. The concerto will be of excellent quality." And so on and so on, every day the same. It worked. Rachmaninoff completed his second piano concerto, and it has become one of most popular classical pieces ever written.

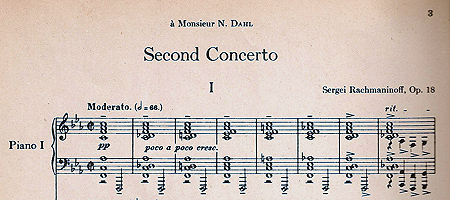

We don't know a great deal about Nicholas Dahl. But every pianist who plays the concerto sees his name on the title page of the score, for the composer dedicated the work to him. So if we have to call a creative lull "writer's block," then maybe there's something universal there after all. For it was the power of mere words that unblocked Sergei Rachmaninoff.

Opening of the 2nd piano concerto, with the inscription to Dahl. The slow minor piano chords evoke tolling church bells. Few pianists have hands large enough to play the left-hand as it is written, without breaking the chords. (Rachmaninoff's huge reach supposedly spanned a perfect 12th — from C to G 1½ octaves above.)

I'm Roger Kaza, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

The above story is told and re-told in most program notes for concerts that feature the concerto. Since many of these are now online, the web is replete with documentation. Some skeptics dispute Rachmaninoff's claim that Dahl's hypnotism was the sole factor in his eventual success at writing the 2nd piano concerto. They point out that Dahl was an amateur musician and an extremely cultured man, and that the act of simply bonding with an encouraging soul, (who, it should be pointed out, also had a beautiful daughter) may have lifted Rachmaninoff's spirits. Another word of encouragement came from the playwright Anton Chekhov, who attended one of Rachmaninoff's concerts. Afterwards, Chekhov told Rachmaninoff he would one day be a "great man."

In contrast, my view is that there is no particular reason to doubt Rachmaninoff's own account, and note that the dedication of a musical score to any kind of "healer" is quite unusual.

Rachmaninoff made many recordings, and also some piano rolls. A few years ago some of these were digitally transcribed, so they could be "played" and recorded on a concert grand. The Telarc CD is entitled A Window In Time: Rachmaninoff Performs His Solo Piano Work.

On a personal note, Rachmaninoff has enlightened me in my playing and teaching, second-hand: one of my horn teachers, Philip Farkas, played a concert under Rachmaninoff's baton, probably in the late 1930's or so. He approached the composer to ask him the "Russian" meaning of a certain expressive marking found in the famous horn solo in Tchaikovsky's Fifth Symphony. Rachmaninoff, who knew and revered Tchaikovsky, explained it to my teacher, and I in turn explain it the same way to my UH students.

Musical examples from the Rachmaninoff Concerto No. 2 in C minor, op. 18. Performed by Van Cliburn, piano, with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Fritz Reiner.

Picture of Rachmaninoff courtesy Wikimedia Commons. Score example published by G. Schirmer, New York.