Picturing Monsters

by Roger Kaza

Today, picturing monsters. The University of Houston's Music School presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The first complete photograph of planet earth, taken from Apollo 8 in 1968, gave us a shock of recognition. There it was, the blue sphere imagined for centuries.

The first complete photograph of planet earth, taken from Apollo 8 in 1968, gave us a shock of recognition. There it was, the blue sphere imagined for centuries.  The picture has been credited for inspiring Earth Day and the environmental movement. It's a peaceful, reassuring image. But, if you live as I do on the Gulf Coast, there is another, far more ominous space photo, taken seven years earlier. That's the year the satellite Tiros III gave us the first view from space of a hurricane.

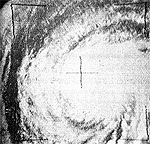

The picture has been credited for inspiring Earth Day and the environmental movement. It's a peaceful, reassuring image. But, if you live as I do on the Gulf Coast, there is another, far more ominous space photo, taken seven years earlier. That's the year the satellite Tiros III gave us the first view from space of a hurricane.

The Atlantic hurricane season officially ended last week, and don't ask me why I'm thinking about them; we just lived through one. Hurricane Ike blasted through the Houston/Galveston area doing over 20 billion dollars in damage. More personally, it took off a good section of my roof. My family is among the lucky. Ike claimed over 150 lives.

A hurricane is a tropical cyclone, which is Greek for "coils of a snake." But this serpentine description is less than 200 years old. That's because we didn't even realize that hurricanes spin like tops until 1821. A Connecticut saddle maker turned amateur meteorologist named William Redfield noticed that trees had fallen in opposite directions as a hurricane moved up the coast. He pondered it and wrote: "This storm was exhibited in the form of a great whirlwind." Bingo. Redfield's observations started the science of hurricanes, and we had our very first mental picture of one.

Before satellites, hurricane warnings came from ships, from islands, or from planes. Even in pre-industrial times, our ancestors had a bit of warning, especially along the coast: deep, leisurely-spaced swells crashing the shore, sometimes accompanied by a brick-red sky. But, for us, the time frame of a hurricane has changed forever. Satellites now detect hurricanes a week or more before landfall. By three or four days prior, you have your marching orders: evacuate, if required, or hunker down and wait it out. The wait can seem interminable. Life grinds to a halt before a hurricane, and it's a strange disconnect. The hurricane itself is moving at breakneck speeds, but the hurricane event is now a slow-motion disaster. Images flood the internet and TV, the monster with its gaping eye brought to you in obscenely high-def detail.

Hurricane Ike at peak intensity.

In September I logged onto the NOAA website a couple times each day, and watched hurricane Ike inch ever closer to my home. The tracking becomes personal. Once a hurricane is well into the Gulf, you know it's going to make landfall somewhere. The dread that the hurricane is aiming directly at you is wedded to a secret craving to witness every bit of its terrifying, chaotic glory — safely of course. We're like Ulysses — tie us to the mast while the Sirens shriek.

So those of us in the Gulf go into hurricane remission about now, and with it our seasonal thrill and dread. But I don't need to wait for next summer's space photos to know what they will show me. Those mythical old maps were right after all. Here be monsters.

I'm Roger Kaza at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Ike destruction at the Moores School of Music, University of Houston.

(Theme music)

For a riveting description of hurricanes, especially the 1900 storm that destroyed Galveston, Texas, there is no better account than Isaac's Storm, by Erik Larson. (Crown Publishers, New York, 1999).

Wikipedia article on Hurricane Ike.

National Hurricane Center website.

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Hurricane, earth and map images courtesy Wikimedia commons. Tree photo by R. Kaza.

The phrase purported to be on many old maps, "here be monsters," or "here be dragons," is almost entirely without corroboration. According to Wikipedia, there is only one known map in existence with such a phrase, the Latin hic sunt dracones, on the Lenox Globe. However, even without any such inscriptions, the old map-makers had great fun drawing the monsters. Below, detail from an old map of Iceland, circa 1590, by Abraham Ortelius.