Equipping Your Clinic

Today, your doctor's office comes into being. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The Journal of Laboratory and Clinical Medicine reaches its hundredth anniversary in October 2015. But let's look at the first volume of this century-old periodical; for in it lie the seeds of the medicine we've come to expect. The editor says that too many doctors think laboratory work comes from a world alien to good diagnosis. He hopes this journal will bridge that chasm. And as we think about our doctor's offices, we realize how well he succeeded. Here, in embryo, emerges the medicine we take for granted.

Take blood pressure: Blood-pressure cuffs had been around for only five years, and they still had to be read with stethoscopes and manometers. Doctors didn't let assistants near them. Now the journal explains systolic and diastolic pressures, and gives only simple interpretations of those readings.

Still, we lay-people today know most of what was being explained to doctors in 1915 -- except for one interesting point: the blood pressures we talk about are for our arms. Their ranges would be much different if we got them from, say, our thighs.

Once your nurse has your blood-pressure, she'll often want an EKG. That stands for Elektrokardiogramm (as it's spelled in German.) The principle of measuring heart-beats electrically was known, but you didn't see it in a doctor's office. Nine years later Willem Einthoven got a Nobel Prize for making the first practical EKG machine. Its use wasn't commonplace until after WW-II.

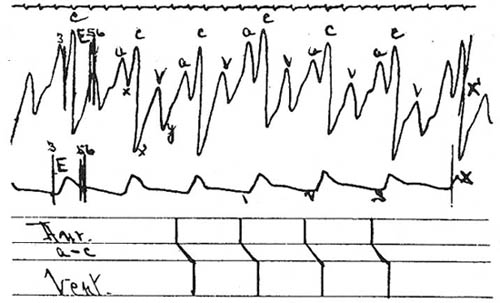

The journal offers a different method for tracing out the heart's pressure pulse. A mechanical microphone, placed over the jugular vein, yields a graph that resembles EKG traces. It's not as sharp and clear, it's limited to one location, but it does give similar information. And this is all about gathering and processing information -- the issue that dominated twentieth century medicine.

Trace of a normal jugular heartbeat

Two articles deal with a poorly understood molecule called cholesterin in Europe, and cholesterol in America. We learn that cholesterol is present in all our cells. It's obviously relevant to pathology, but how? One author notes that it's low in an anemic person's blood. He hints at factors related to arterial sclerosis and obesity. But he finishes by admitting that he cannot reach "any conclusions as to the exact action of cholesterol." In fact, that would take another half century.

Still, it all points out the direction medicine was headed. I suppose it's especially good news that many of these old articles address problems that we now know how to combat -- chicken pox, small pox, syphilis, TB, typhoid fever ...

Here we have a wonderful view of our world emerging from the studious, curiosity-driven work of so many doctors, a century ago. Why do these old articles seem so prescient? I think it's because their authors focused so clearly -- so wisely -- on identifying their own ignorance, not on displaying intellectual authority.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

The Journal of Laboraory and Clinical Medicine. Vol. 1 (Oct. 1915 to Sept. 1916). All images are from this source.

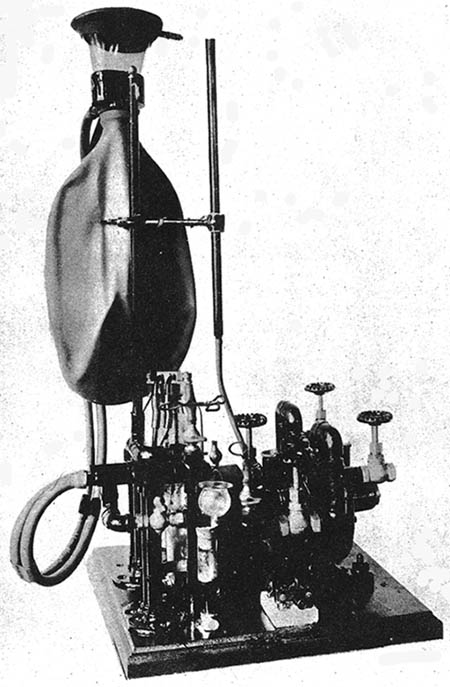

Upper portion of a new (in 1915) apparatus for delivering a general anesthetic