Airplanes Without Tails

Today, airplanes without tails. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I love watching large birds in flight. And I notice the way many of them fold in their tails during level flight. They become nearly all wing. So why not an all wing airplane?

Well that idea harbors good news and bad news. The good news is that the thin frontal profile of a wing offers little drag. Keep it thin, and it will be as efficient as a hawk.

The bad news is twofold: First, control: Control surfaces on a tail have a lot of leverage. But controlling flight from the back of a wing, so close to the center of lift, gives much less leverage. Control gets tricky. Hawks trim their soaring flight with small movements of wingtip feathers. But they flare their tails when they land, or when they have to maneuver sharply.

The bad news is twofold: First, control: Control surfaces on a tail have a lot of leverage. But controlling flight from the back of a wing, so close to the center of lift, gives much less leverage. Control gets tricky. Hawks trim their soaring flight with small movements of wingtip feathers. But they flare their tails when they land, or when they have to maneuver sharply.

The second drawback is more obvious: Soaring birds usually have small heads and slim bodies. But, if a flying wing is thin, there's little vertical space for pilot, passengers and cargo. To stay relatively thin, a flying wing has to be huge.

Still, we need to remember Lienhard's first rule of technological experimentation: If anything looks like it could work, sooner or later someone will try to make it work. That's why flying wing aircraft go back, even before the Wright Brothers.

Many 19th-century airplanes were flying wings. We've largely forgotten the ones made by Penaud, Ader, Ellehammer -- even though they almost succeeded. Some of Lilienthal's successful gliders had no tails. And the idea lingered after powered flight was established. Beginning in the late 1920s, C. L. Snyder, a podiatrist from South Bend, Indiana, built a series of tailless airplanes. (His designs were inspired by the shape of a boot heel.) In the 1930s, he and other flying wing designers built workable airplanes, but none did well enough to dent the

private market.

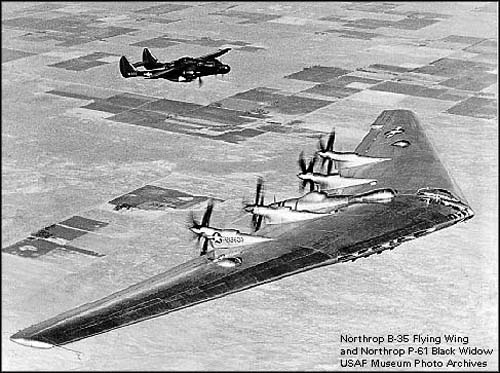

Then, in 1940, the new Northrop Corporation set out to build a huge 173-foot flying-wing bomber. They began with a one-third-size two-engine, single-seat version. It did poorly in test flights, but Northrop went on to build its B-49 bomber. It should've been no surprise that it suffered serious problems of function, control and handling. Yet one of those one-third-size versions has been restored, and it flies today. Its pilots speak well of it, but they're careful. They acknowledge it can be tricky.

Then, in 1940, the new Northrop Corporation set out to build a huge 173-foot flying-wing bomber. They began with a one-third-size two-engine, single-seat version. It did poorly in test flights, but Northrop went on to build its B-49 bomber. It should've been no surprise that it suffered serious problems of function, control and handling. Yet one of those one-third-size versions has been restored, and it flies today. Its pilots speak well of it, but they're careful. They acknowledge it can be tricky.

And new flying wing designs appear. As we better understand the aerodynamics of high speed flight, the problem changes. The simple flying wing segues into the delta wing form. The Stealth bomber had a delta shape, so does a large airplane design that Boeing engineers are now flying in a pilotless reduced-scale version.

Meanwhile, those huge birds, soaring over the flat fields of coastal Texas: They do not enter our ongoing conversation about what is possible. They simply unfurl their great four and five-foot wings, ride the thermals, and wait for us to figure it all out.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

S. Joiner, And Then There Was One. Air & Space, Feb/Mar 2007, pp. 40-47. Joiner tells about ten one-of-a-kind surviving airplanes. One is the Northrop N-9M -- the surviving third-size version of the YB-49 flying wing bomber and its precursor, the YB-35.

Click Here to learn about very early flying wings

Click Here for a Wikipedia article on flying wings, and Click Here for a list of 20th-C flying wings.

Click Here for a discussion of the mechanics of bird flight:

Click Here for a pilot's comments on the flight characteristics of the Northrop YB-49 flying wing.

Bird photos by J. H. Lienhard.

The YB-35, propeller-driven precursor of the jet-powered YB-49 Flying Wing.