Bertha Benz's Ride

Today, Bertha Benz's ride. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Karl Benz is often given credit for inventing the automobile. Well, no one person invented the automobile. Internal-combustion-driven vehicles preceded Benz just as surely as light bulbs preceded Edison and telephones preceded Bell. But a good part of the reason he gets the credit was his wife Bertha.

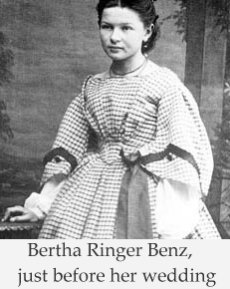

In 1888, Karl and Bertha Benz had been married for eighteen years. He was 43, she was 39, and they were living in Mannheim, Germany. Karl was an engineer who'd received a patent on his new automobile three years before. Bertha had the mind of an engineer herself. She'd worked closely with Karl and she knew the machine intimately.

In 1888, Karl and Bertha Benz had been married for eighteen years. He was 43, she was 39, and they were living in Mannheim, Germany. Karl was an engineer who'd received a patent on his new automobile three years before. Bertha had the mind of an engineer herself. She'd worked closely with Karl and she knew the machine intimately.

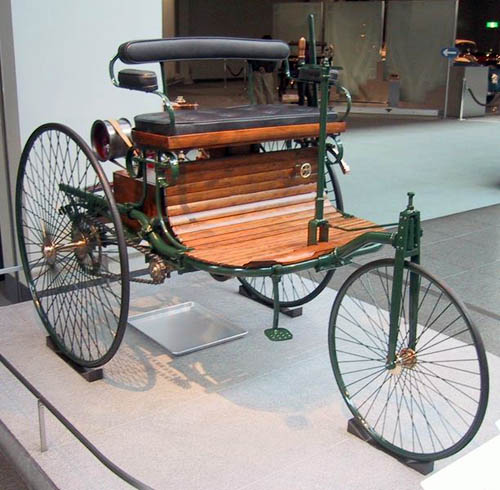

And she was frustrated: Karl, the perfectionist, was trying to get everything just right before he took the next step. Bertha knew perfectly well that we can't perfect a design before we field-test it. And she had more faith in Karl's auto than he did. He'd finished two models and was working on a third. They were light, 3-wheeled vehicles, powered by his own single-cylinder, gasoline engine. They got about 25 miles per gallon.

Now Bertha hatched a plan: She and her young sons Eugen and Richard would slip out and make the 65 mile journey from Mannheim to Pforzheim to visit her mother. In a world with no service stations or roads meant for car traffic, this was a step into the void.

In fact, she was even unsure of the route. She knew she'd have to go through towns with pharmacies where she could buy gasoline. It was then being sold as a cleaning fluid. Early one morning she left a note for Karl on a table. The three of them pushed a car out of the shed and far enough down the road so they could start it without waking him.

Bertha did keep Karl informed by telegram. Meanwhile: She used her hatpin to clear a clogged fuel line; when an ignition wire short-circuited, she improvised an insulator from her garter. She stopped in the town of Bauschlott to get a shoemaker to replace the leather on a brake shoe. She enlisted two farm boys to help push the car up a hill that its two-and-a-half-horsepower engine couldn't handle.

I said at the beginning, this was not the first automobile. But when Bertha finished her Odyssey and telegraphed Karl to say they were safely in her mother's house, history was made. The auto had found the open road. It had stated its purpose.

Karl telegraphed back asking Bertha to send him the drive chains. He needed them to get his third car ready for an exhibition in Munich. For he now understood that they had a finished product. Well, almost finished -- he also added a low gear so it could climb hills.

Munich was dazzled by the machine. Crowds of pedestrians ran after it in the streets. The automobile had its beachhead in the public's heart. It was here to stay -- and all because Bertha Benz had the nerve to take one giant leap for mankind.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

A Woman Sets the World in Motion. Engine: Englisch Für Ingenieure, Nr. 2, Juni 2008, pp. 58-60.

B. R. Kimes, The Star and the Laurel: The Centennial History of Daimler, Mercedes and Benz, 1886-1986. (Montvale, NJ: Mercedes-Benz of North America, 1986). See especially, pp. 42-43.

For You-Tube images of the Benz auto in motion, And a reproduction of Bertha's riding it, click here.

See also the Wikipedia articles on Karl Benz and Bertha Benz.

A year after this episode first aired, I learned that a German organization has created the Bertha Benz Memorial Route in western Germany. You may read about it in German by clicking here.

Image of Bertha Benz is courtesy of the Mercedes-Benz Company. Image of the 1886 Motorwagen is courtesy of Wikipedia.

The 1886 Benz Motorwagen.