E. Ball Hughes & Perspective

Today, a sculptor's ghost speaks. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

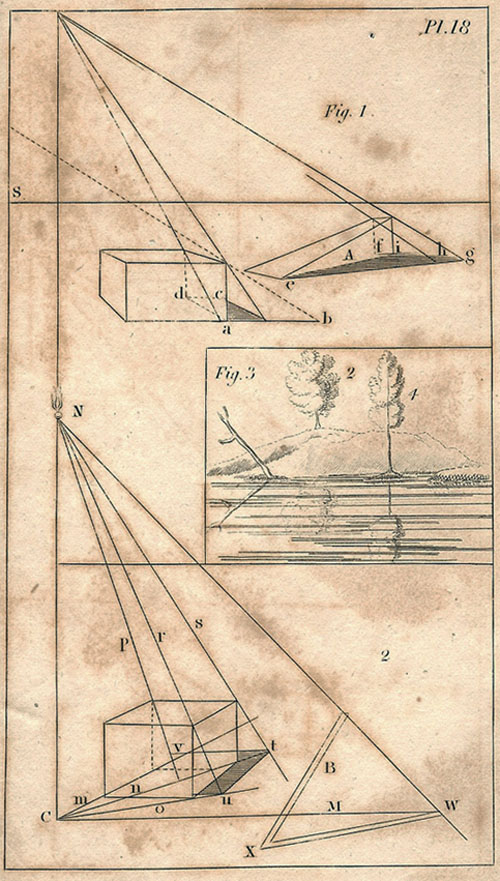

I have this old book, Easy Lessons in Perspective -- a small frayed relic, printed in 1830. It gives no author's name, only the publisher. The new generation of fast roller presses had just come to America, and this is one of our early mass-produced books. The steel plate illustrations then had to be printed separately. So they're all tipped in at the end of the book. (Imagine learning to make perspective drawings by reading words, then having to flip to the end for the relevant picture.)

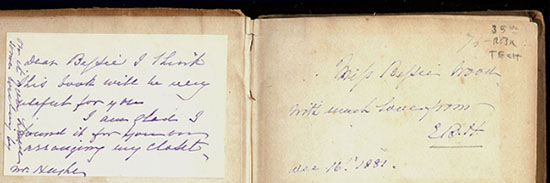

The owner has penciled a note to himself on the back flyleaf. He describes how to handle the point of origin of light, and the vanishing point, in a sketch. He's inscribed the front flyleaf to one Bessie Wood in 1851. He tells her that the book turned up when he rearranged his closet. He thinks she'll find it useful.

He signs himself as E. B. Hughes. This is the artist E. Ball Hughes (sometimes listed as Robert Ball Hughes). He was an artistic prodigy, born in England in 1806. By the time he moved to America at the age of 23, he'd already won medals from the Royal Academy.

This book came out the year after he arrived in New York, and we can only guess that he was still honing his abilities when he read it. By the time he'd signed it over to Bessie, he'd built his American career. He'd done significant sculptures of Alexander Hamilton, Washington Irving, and Dewitt Clinton.

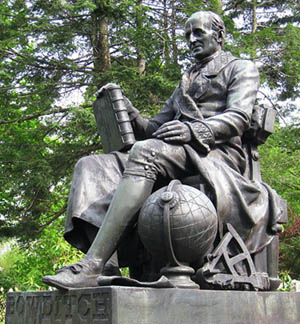

A high-relief marble sculpture sits in New York's Trinity Church, and others in the Boston Athenaeum. Hughes designed coinage for the US mint. His most famous surviving work is a great statue of early American mathematician and geographer Nathaniel Bowditch. We see it today in beautiful Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Watertown, Massachusetts -- larger than life, the first large cast bronze statue made in America.

A high-relief marble sculpture sits in New York's Trinity Church, and others in the Boston Athenaeum. Hughes designed coinage for the US mint. His most famous surviving work is a great statue of early American mathematician and geographer Nathaniel Bowditch. We see it today in beautiful Mt. Auburn Cemetery in Watertown, Massachusetts -- larger than life, the first large cast bronze statue made in America.

And so he rearranged his closet, found this book, and wondered if Bessie Wood might like it. I wonder who she was, and I hope she too profited from it. Hughes certainly did. He took perspective in an odd direction. He drifted further and further toward relief sculpture -- that is, shallow three-dimensional forms projecting from their own flat background. Relief creates the illusion of depth in sculptures that hang on walls.

As an older man, Hughes took up yet another form of relief carving, pyrographics or woodburning. He created powerful images by applying a hot poker to a board. That didn't make much money, but it satisfied his need to keep finding new perspectives -- new ways to recreate three-dimensional realities for us all to see.

Now I hold this old book (with its E. Ball Hughes sketches on a flyleaf) and I know his ghost is there. Hughes reminds us how he came to America long ago and found a place to breathe and expand. That lingering presence helps us to remember the fine genius he brought here, and how he left us the better for having become one of us.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Easy Lessons in Perspective. (Boston: Hilliard, Gray, Little and Wilkins, 1830). While no author is given, the book is dedicated to British painter and engraver John Raphael Smith, who died 18 years before it came out. All images are from this source except the photo of Hughes' statue of Bowditch. The latter is courtesy of Wikipedia commons.

Another copy of Easy Lessons in Perspective has been posted online. Click Here. (Of course, this one does not contain the marginalia that I talk about.)

Correction and Addendum: After this program aired, I received an email from Kathleen M. Garvey Menendez, Curator of the E-Museum of Pyrographic Art:. She pointed out that E. Ball Hughes' wife was named Eliza -- that the E. Ball Hughes who cleaned out the closet was probably the sculptor's wife. If one reads the inscription in the book closely, the date is more likely to be 1881 (after the sculptor had died, but while his wife still lived), than 1851. It appears that E. Ball Hughes, the sculptor, never did part with this book.