Two German Phrasebooks

Today, UH scholar, Richard Armstrong tells us about German phrasebooks. The Honors College at the University of Houston presents this program about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The foreign language phrasebook was a dangerous invention. You see, a phrasebook gives you the appearance of knowing more of a language than you actually do. It scripts you into scenarios like some bit-part actor in a bad movie. You stumble through your part as best you can, but most of the time, you can't even understand the other half of the conversation. You do well just to get through all your lines with a little dignity.

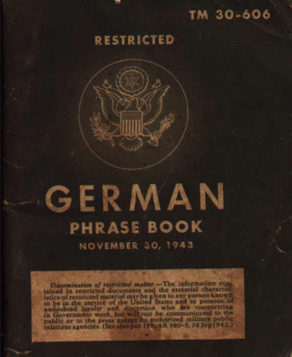

But old phrasebooks make fascinating reading for that very reason. With time, these little books ripen into wonderful scripts for historical drama. They suggest the needs and anxieties of a bygone era; we begin to imagine the troubles people had long ago. Take these lines: "Throw down your arms!" "Raise your hands!" "Line up!" These are from a German phrasebook issued by the US Army in 1943. The GI's linguistic needs were terribly precise. Essential nouns for those days were: booby trap, pillbox, dive bomber. A conversation included sentences like: "Have you laid any mines here?" "Stop the bleeding!" "Lift me carefully." "I have been poisoned."

Now let's look at an even older German phrasebook. It has some pretty basic things. "What country do you come from?" "Where is it?" Some phrases seem quite appropriate for travel in Germany: "Would you like to drink good wine?" But then other phrases begin to show their age. "Give me a candle." "Do you have fodder for my horse?" "Where is your master?" "My Lord would speak with you."

Sorry, I should have stressed this is a much, much older German phrasebook. It dates from the tenth century AD, and it's in a medieval language known as "Old High German." Someone made it for a traveler coming from what is today France—one who needed to negotiate the usual needs. But the selection of phrases speaks volumes about the dramas this traveler would encounter. "Give me my sword!" "Give me my shield!" "I will not go into your house!"

The traveler appears rather sanctimonious. There is a great fuss about attending matins, the early morning Church service. "Were you at matins this morning?" "Did you see my Lord at matins?" "Why did I not see you at matins?" Other phrases suggest pretty damning reasons why someone didn't get up early to go to Church. "I didn't want to go." "You lay with a woman in your bed!" "On my head, if your master were to find out, he'd be furious with you!" "A fool makes whoopie gladly!" (Well, that last one was edited for radio.)

But this traveler was no saint, and was equipped with phrases we might well call "fighting words." "Strike him on the neck!" "Listen, fool!" "How'd you like your horse's halter around your neck!" The most amazing phrase is an insult that could only be followed by blows: "a dog's posterior in your nose!" I have to wonder if this phrasebook user made it home alive. But this reminds me: to be useful to a real traveler, a phrasebook should emphasize the most essential human expressions: please, thank you, excuse me, and even, I'm sorry.

I'm Richard Armstrong, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Click here to download a complete copy on the US Army 1943 German phrasebook.

On the study of foreign languages in the Middle Ages generally, see: B. Bischoff, "The Study of Foreign Languages in the Middle Ages." Speculum 36.2 (1961): 209-224.

On the Old High German phrasebook, see: J. K. Bostock. A Handbook on Old High German Literature. Second edition, Oxford: Oxford UP, 1976. Pages 101-103.

F. Jolles. "The Hazards of Travel in Medieval Germany: An Attempt at an Interpretation of the altdeutsche Gespräche." German Life and Letters 21(1968): 309-319.

The great German philologist Wilhelm Grimm, when he came in his scholarly commentary to the insult, "a dog's butt in your nose," merely wrote, "I must pass over this incomprehensible line." Kleinere Schriften (Berlin, 1883), vol. 3, page 494.

The phrasebook entries are found in two manuscripts: Paris, Bibliotèque nationale ms. lat. 7641 and Rome, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana codex reg. lat. 556, page 50b.

The edition of the medieval phrasebook I have consulted is: W. Braune,ed., Althochdeutsches Lesebuch (Tübingen: Max Niemeyer, 1969): Pages 9-11.