Hell Gate

Today, Hell Gate in the East River. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Dutch explorers of Manhattan Island called the East River Hellegat. That meant bright passage. Shipping between Europe and Manhattan was shorter and safer for ships that followed the upper shore of Long Island and entered the East River from the north. But, once on the River, they reached a treacherous stretch of about a mile -- fickle currents and submerged rocks. The worst of it lay next to Astoria, in Queens, under the south side of Wards Island. After the name Hellegat changed to East River, this twisty, mile-long, stretch kept a version of the old name. Now it was Hell Gate -- an ominous pun on the Dutch name.

So much of our nation's shipping passed through Hell Gate, and we suffered a steady attrition of life and property. New Yorkers first pressured the US government to do something about these waters in 1845. Within six years, the Coast Survey had created maps and marked dangers to shipping. But those maps only highlighted the dangers. They cried out for some sort of engineering fix.

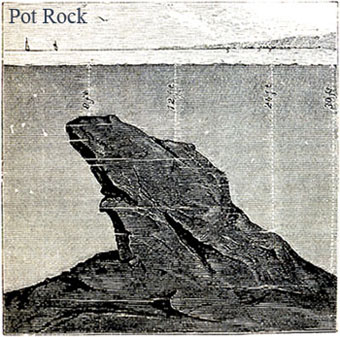

When Congress provided no relief, New Yorkers went at the obstructions with explosives. Take, for example, Pot Rock -- rising like a rhinoceros horn from a depth of thirty feet to within eight feet of the surface. It lay right next to a shipping lane. They went at it with seventeen tons of explosives. But that only blunted it. It was still poised to gore the hull of a large ship.

When Congress provided no relief, New Yorkers went at the obstructions with explosives. Take, for example, Pot Rock -- rising like a rhinoceros horn from a depth of thirty feet to within eight feet of the surface. It lay right next to a shipping lane. They went at it with seventeen tons of explosives. But that only blunted it. It was still poised to gore the hull of a large ship.

The Corps of Engineers was starting to take an interest when the Civil War brought work to a halt. But war made it clear that shipping safety was a national security concern. So the government went to work. Rocks were cut and ground. But mostly, they blasted away at the forest of subsurface pinnacles.

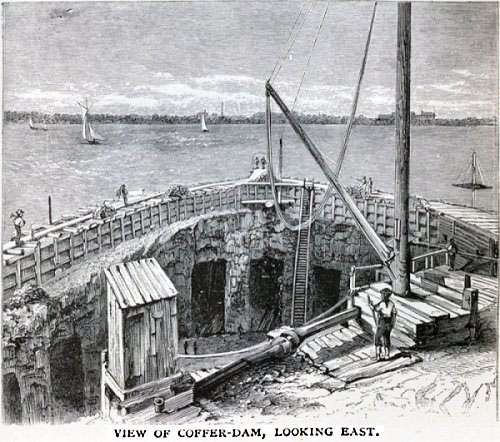

And there was Hallet's Point, a three-hundred-foot rocky promontory that reached out from Astoria to catch ships, and to shape dangerous river currents. Removing Hallet's Point was a daunting project. Workers tunneled down into the rock from behind a great coffer dam. They cut a spider web of deep tunnels out under the river. They placed tons of nitroglycerin in the tunnels, and reduced that geographical feature to rubble.

Today, only some tidal current reversals remain -- occasional challenges for kayaks and canoes. Architect Gustav Lindenthal's Hell Gate rail bridge was opened over the north end of the channel in 1916. And I love the park just below that bridge. The scene is idyllic. It seems to mock the name Hell Gate.

So the origin of one more name has been lost in the fog of time. Think of the LA Dodgers or Utah Jazz. Or who remembers that 3-M Company was once Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing -- our major sandpaper source? New Yorkers, spurred by the sinister name Hell Gate, still boast of their treacherous river. But those dangers were put to rest by extraordinary engineering over a century ago. The name is now only an echo of a forgotten time.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

A surprisingly complete treatment of the clearing of Hell Gate was written five years before it was finished. See the Nov. 1871 issue of Scribner's Monthly Magazine, Vol. 2, pp. 33-53. "The Unbarring of hell Gate. (no author's name given). All black-and-white illustrations are from this source. For further information, see Wikipedia.

Click here, or on the thumbnail image to the right, for a comparison of the Hell Gate area shown at the time of the 1871 article (with all the many obstructions), and a Google Earth image of the area today.

Click here, or on the thumbnail image to the right, for a comparison of the Hell Gate area shown at the time of the 1871 article (with all the many obstructions), and a Google Earth image of the area today.