Chedworth Villa

Today, Rome, in England. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The Bristol Channel cuts a smiling mouth in the face of southwest England. Follow the Channel to its tip, then go another thirty miles and we reach the tiny village of Chedworth in the gentle wooded Cotswolds hills.

There, in 1864, a gameskeeper found that burrowing rabbits had kicked up bits of tile from underground. The land belonged to the Earl of Eldon. He organized an excavation; and, sure enough, this had been the site of a Roman villa.

Contact between Britain and the Greco-Roman world went back to early seagoing Mediterranean peoples who'd traded with Britain for tin. Julius Caesar established Roman political influence there. Finally, in 43 AD, the Emperor Claudius ordered an invasion of Britain. Within twenty-five years, Britain had become one more Roman province. And so it remained until Rome began losing control in the fifth century, and when Saxons became the next invaders.

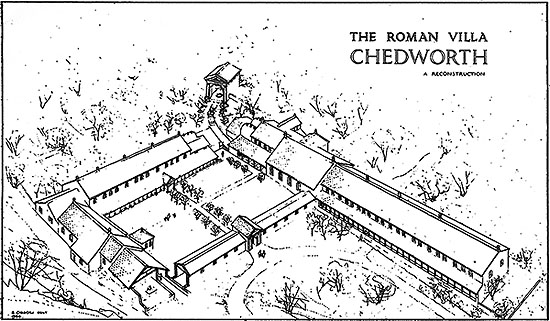

Chedworth Villa was built around 150 AD. It saw expansion and rebuilding for two centuries and was then abandoned, perhaps the victim of a rash of political troubles. But, during its long life it was an elegant country estate -- most likely owned by wealthy Romanized Britons. It's a Roman design, but builders made concessions to a colder climate and local resources. And the elegant tile was largely made locally. Many other villas have been found -- some nearby. But none show such grandeur, so well preserved.

Chedworth Villa was built around 150 AD. It saw expansion and rebuilding for two centuries and was then abandoned, perhaps the victim of a rash of political troubles. But, during its long life it was an elegant country estate -- most likely owned by wealthy Romanized Britons. It's a Roman design, but builders made concessions to a colder climate and local resources. And the elegant tile was largely made locally. Many other villas have been found -- some nearby. But none show such grandeur, so well preserved.

The villa is shaped like the letter J, with a garden courtyard nested in it. The back of the J held private rooms, a large dining room, and a kitchen. Bedrooms lined the bottom of the J. Those two wings meet in an elaborate system of Roman baths -- steam rooms, cold rooms, changing rooms. Finally, the short upstroke of the J was for a smaller kitchen, a latrine, and some utility rooms.

It was big: 20,000 square feet of living space lay upon a lot four times that size. Excavations have exposed foundations, floors, old implements, and vast tile work -- so much elegance that seems so out-of-place. As I try to make sense of it, I think of A.E Housman. He wrote about a place called Much Wenlock only fifty miles from here. He said,

On Wenlock Edge the wood's in trouble

His forest fleece the Wrekin heaves;

'Tis the old wind in the old anger,

But then it threshed another wood.

Then, 'twas before my time, the Roman

At yonder heaving hill would stare: ...

The tree of man was never quiet:

Then 'twas the Roman, now 'tis I. ...

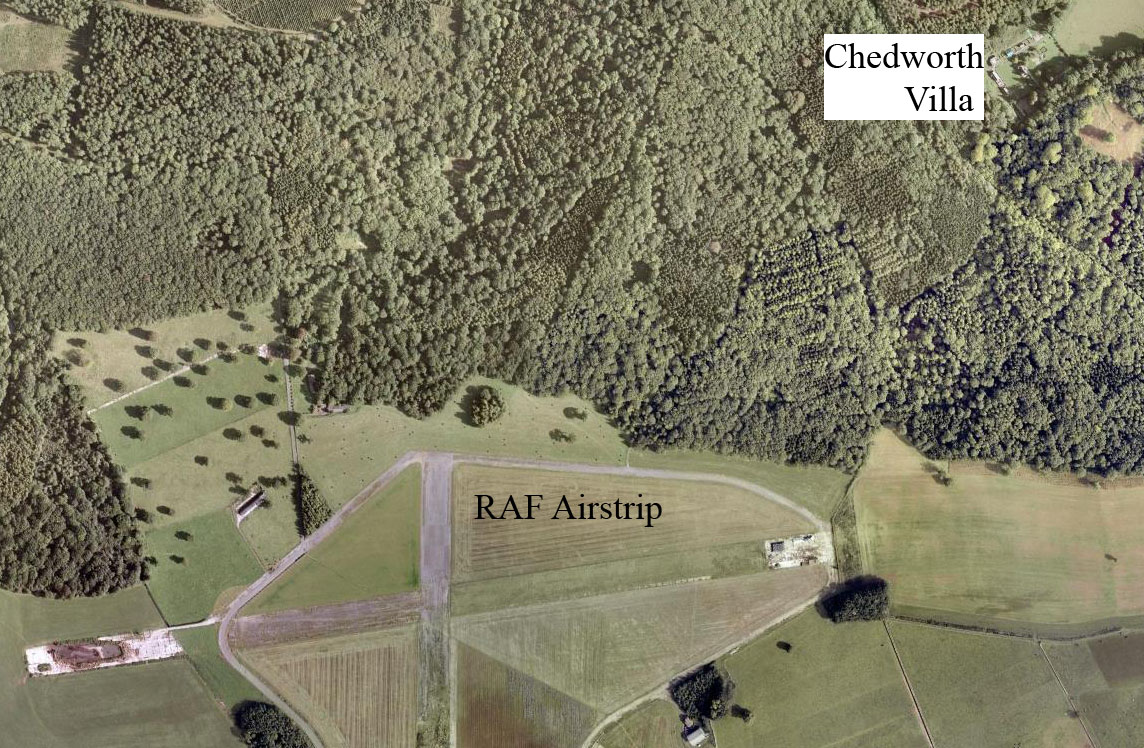

We need walk only a half mile through the forest behind Chedworth Villa to see what Housman meant. We emerge on a WW-II RAF airstrip.

So the tree of man never was quiet. Between Housman's "Roman and I" came the Saxon, Viking. Norman, and Hitler's attempt. We really do live closer to that villa in the forest than we first imagined.

I'm John Lienhard at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Chedworth Roman Villa, Gloucestershire. (Lingfield, Surrey, England: The National Trust Brochure, 1981). (I am grateful to Marjorie deHartog for providing this source.)

See also, An online history of Roman Britain.

Artist's conception of Chedworth Villa, courtesy of the National Trust

Both aerial images courtesy of Google Earth