Munich Museum, 1912

Today, a museum is born. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Munich's Deutsches Museum was first proposed by engineer Oskar von Miller in 1903. Prince Ludwig of Bavaria backed him, and the museum opened three years later. It has, ever since, held one of the world's finest collections in science and technology. I got there in the mid-80s and was quite blown away by it.

The museum's website is like any major science museum's -- children's programs, concerts, flashy thematic displays, community outreach. But we get a much a different view in a much older source, the 1912 Century Magazine. The Museum then occupied 68 rooms in two temporary buildings, while the permanent building was being erected on an island in the Isar River, near Munich's center.

Like Edison, Miller was a famous electric power pioneer. He engaged the German engineering establishment in building the Museum. One exhibit developer was Nobel-Prize-winning electrochemist Wilhelm Ostwald. It was Ostwald who identified two ways we try to achieve perpetual motion. Not only do we fail when we try violate energy conservation; inventors also fall into the trap of trying to build engines that reduce entropy.

America's Smithsonian Institution was likewise given its shape and direction by an electrical pioneer, Joseph Henry. And we're reminded that fine museums really do rest upon great intellects.

The article tells us it would take months to digest even this temporary Museum. Still, like any museum, this one reflects the times. Earth's geologic history was getting huge attention just then, and mining was a primary industry. Many exhibits deal with stratigraphy, natural resources, and deep-mining techniques.

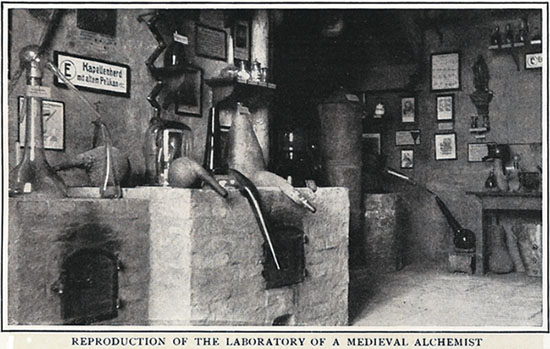

Germany had created the world's dominant chemical industry and gone on to become, for a season, the leading industrial nation. So the Museum held many exhibits on new chemical processes. It also included us a complete replica of a medieval alchemist's laboratory -- one that could've been a stage for the opera Faust.

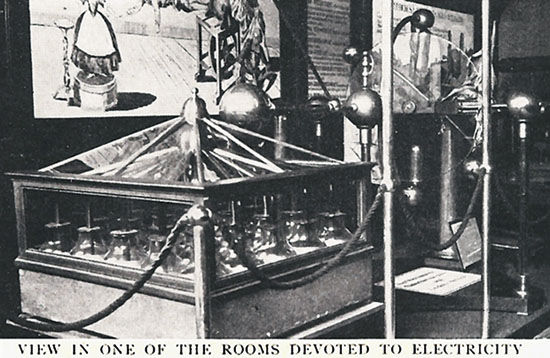

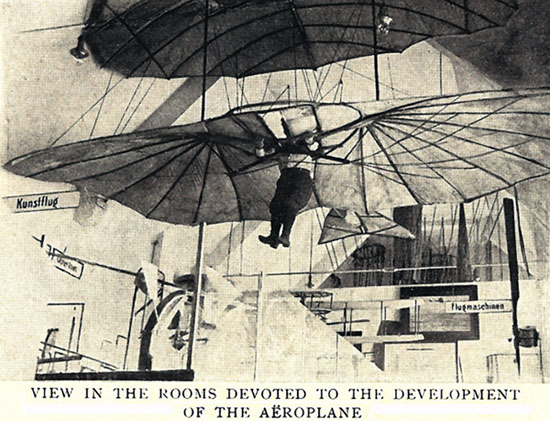

The Museum had a lot of new electric technology. And a smaller gee-whiz display showed the new flying machines. The two main items can still be found in most large air museums today: a Lilienthal hang glider and the Wright aeroplane. But, today, the Deutsches Museum has a large separate airfield just outside Munich.

Power generation was also a strong concern. There's a fine exhibit on the history of power plants -- Savery, Newcomen and Watt, all the way to the new gasoline engines. But just as important is a unique exhibit on von Guericke's 17th-century vacuum pump. By demonstrating what force atmospheric pressure brings down upon a vacuum, he made it clear that gases would drive engines.

The author finishes by noting that the Deutsches Museum reflected the source of Germany's greatness in the good times before two wars: Technology and science had put her there. We need to remember that, in today's tenuous times.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

For today's museum, see the Deutsches Museum website:

H. S. Williams, Germany's Greatest Museum: The Deutsches Museum in Munich. The Century Magazine, Vol. LXXXIV, New Series LXII, No. 6, October, 1912, pp. 933-941. All images are from this source.

Ludwig would soon become the last of three King Ludwigs of Bavaria. All were great promoters of the arts.