Distaffs and Home Economics

Today, the distaff side. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

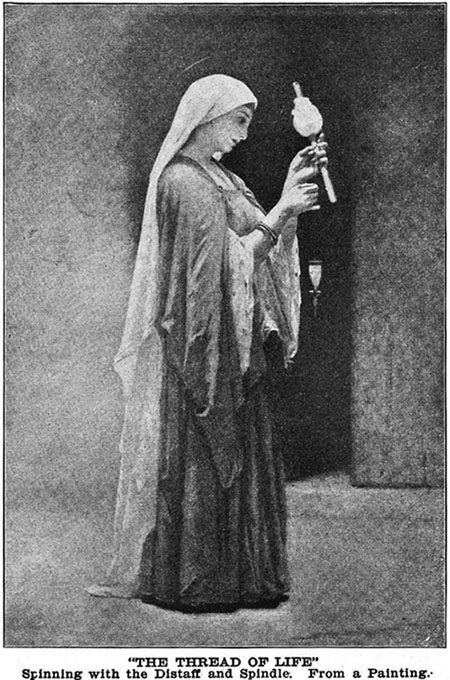

We still called the female branch of a family the distaff side when I was young. Now the word distaff is almost forgotten. It was a staff that held a clutch of maybe wool or cotton. A thread of the fiber was pulled out, twisted, and tied to a hanging spindle. The spindle was then spun and the operator, presumed to be a woman, kept it spinning as it drew out, and wound, the thread.

We still called the female branch of a family the distaff side when I was young. Now the word distaff is almost forgotten. It was a staff that held a clutch of maybe wool or cotton. A thread of the fiber was pulled out, twisted, and tied to a hanging spindle. The spindle was then spun and the operator, presumed to be a woman, kept it spinning as it drew out, and wound, the thread.

Distaffs have been used since the Late Stone age. Spinning wheels began replacing the hanging spindle over a thousand years ago in India. They were taken up in Europe during the middle ages.

All the while, distaffs were symbolic of an ancient division of labor. Spinning was to be used by women to fill spare moments of their multitasking lives. A 15th-century book by William Caxton remarks that "Women comynly do not [meet together] but to spynne on the distaff." Another early writer turned that into a command: "Let thy dystaffe be alwaye redye for a pastime." And, as women started asking more out of life, they looked back at the symbolic distaff. As early as 1748, poet Esther Lewis acidly wrote,

But, Sir, methinks 'tis very hard

From pen and ink to be disbarred:

Are simple women only fit

To dress, to darn, to flower, or knit,

To mind the distaff or the spit?

Now I find a 1907 Library of Home Economics volume on Textiles and Clothing. Its editors included Ellen Richards, born Ellen Swallow. Since she'd done so much before she married Robert Richards, we now call her Ellen Swallow Richards.

She was MIT's first woman graduate. After her degree in chemistry she went on to create the subject of sanitary engineering at MIT and became its first female faculty member. But bringing other women on board a century ago was a challenge, so Richards did an end run. She developed home extension courses in the domestic arts. Those courses soon blossomed into the new academic subject of Home Economics. "Home Ec" is anachronistic now that women blend freely into regular curricula. But in this old book the wisdom of Richardson's sedate assault on a dying social order plays out.

The author is one Kate Heintz Wilson; and her home-study course is one more a spearhead in the movement to bring women into universities. With that subversive agenda in mind, we trace the beautifully illustrated opening section on Primitive Methods. Nine pictures show women holding distaffs. The symbolism is pungent.

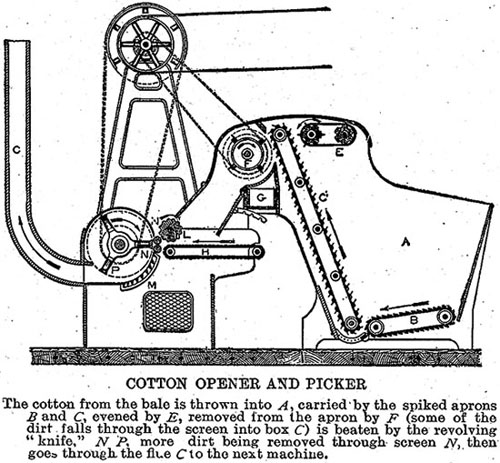

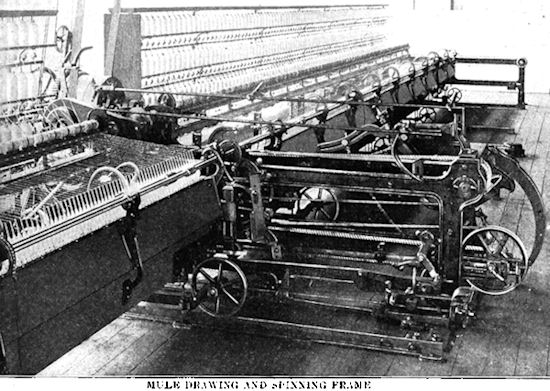

But keep going: The book takes us on the road to spinning jennies, then to powered spinning and drawing frames -- from hand looms to a textile industry. The distaffs segue into photos and line drawings of factory textile machines. They give way to fiber analysis and to the chemistry of cleaning.

And the message of suffrage is clear. The path to freedom leads from distaffs to slide rules and drawing boards. It ultimately leads to supercomputers and spectrometers, to a place where, if we weave or embroider, we can do so for pleasure beyond mere survival.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

K. H. Watson, Textiles and Clothing. The Library of Home Economics: A Complete Home Study Course (Chicago: American School of Home Economics, 1907). All images from this source.

For more on Ellen Swallow Richards, see Episode 794.