Roll over Beethoven

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, Toscanini plugs Beethoven. The University of Houston's Honors College presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

"To some it's Napoleon, to some it's philosophical struggle, to me it's allegro con brio." That was conductor Arturo Toscanini talking about Beethoven's Eroica Symphony. To us, though, the Eroica is elevators, cartoons, commercials and non-stop radio. Great music is everywhere, which may well mean that it's nowhere. And Toscanini's American career might explain this contradiction.

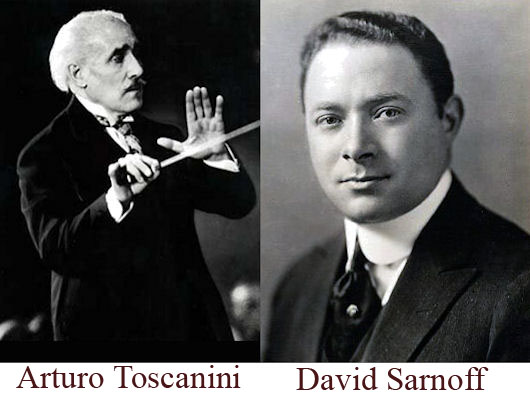

When radio executive David Sarnoff of RCA brought Toscanini to the US in 1937, the Italian conductor was already hailed as one of the great interpreters of Verdi, Wagner and the German romantics. But he had particular attraction for an American audience.

Not only was Toscanini an outspoken anti-fascist who loathed Mussolini; he was also famed for a bearing as imperious and authoritarian as, well, Mussolini's. Who better than Toscanini to conduct a rapidly growing American middle class on a tour of musical monuments?

Toscanini and Sarnoff transformed America's commercial and cultural landscape. Sarnoff gave Toscanini his own orchestra, while Toscanini gave Sarnoff the seal of great art. The tandem tapped into a vast and eager audience. The New York Herald rhapsodized: "The vast increase in the popular appetite for the greatest things that music has to offer is neither a delusion nor a hope nor a dream. It is an actuality." Even then, though, certain voices wondered if radio, television and LPs spelt the realization of a dream or a nightmare.

On the one hand, this civilizing mission was admirable. Why shouldn't we all be taken to the dizzying heights of art? On the other hand, the same impulse might level those summits: the Alps, in effect, would become a parking lot. Aaron Copland, no enemy of the common man, worried over the sheer size of the new audience. And Igor Stravinsky feared radio's "incredible facility." He said, "Just as one can look without seeing, one can listen without hearing."

Toscanini came to define great music for postwar Americans. His striking Christ-like portraits printed in Life magazine, the nearly sacred connotation of his title "Maestro", the hushed voice with which he was introduced on the broadcasts: it was all testimony to the genius of American hucksterism no less than to Toscanini's musical genius.

Toscanini also defined the canon of great musical works. His dislike for contemporary composers (shared by his corporate sponsors) turned the living room into a museum, a gallery of Great (and mostly German) Men whose works would be played (and replayed) until we turn off the radio or step out of the dentist's office. Before Toscanini, conductors had also been composers or advocates for new composers. After Toscanini, conductors became curators of sacred relics.

In American culture, writes the critic Joseph Horowitz, "great music's exclusivity was made a democratic privilege." Some might welcome this historical trend, others bemoan it. But, for me, echoing Toscanini, it is all allegro con brio.

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J. Horowitz, Understanding Toscanini. (New York: Knopf, 1987).

The audio clip at the end of the episode is from Beethoven's Sym # 3 in E-flat Major, Op.55 Eroica, Movement 4. Finale, Arturo Toscanini with the NBC Symphony Orchestra, Vol. 1 1998 BMG Classics No. 74321 55835 CD 2 Track 4.

(Fair use images courtesy of Wikipedia)