The Steam Navy

Today, pruning hooks into spears. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

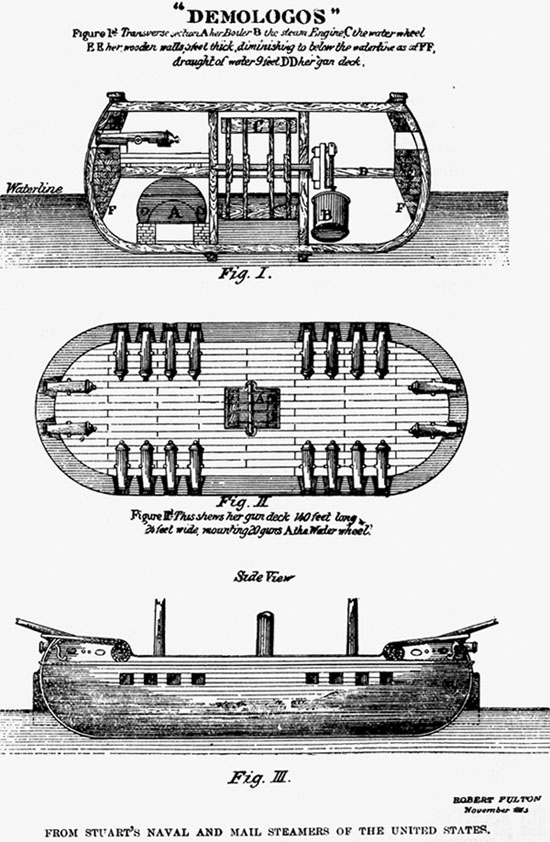

The plowshares-to-swords story of the US Navy and steam spanned two wars. Like most military technology steam warships sprang from civilian invention. The Navy's first steamship was built in New York during the waning days of the War of 1812. It was called Demologos or Word of the People, and its builder was Robert Fulton. Fulton's original steamboat patent was only eight years old. Fulton had aggressively built commercial riverboats. Others had built steamboats before Fulton; but it was he who'd quickly brought them into wide public use.

Demologos was a radical design: The engine and paddlewheels were sandwiched between two hulls, where enemy fire couldn't reach them. Fulton died a few months before it was finished, and the ship was renamed The Fulton in his honor. During the years of peace that followed, The Fulton saw only ceremonial service. Finally, in 1829, someone's carelessness in its powder magazine caused an explosion that blew it to bits.

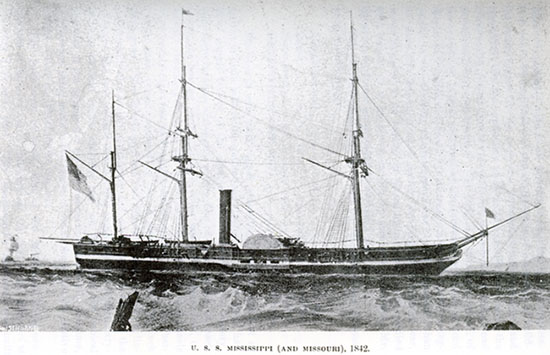

So what did the Navy do, now that the advantages of steam were clear? Well, they bought a small steamship, used it for three years in the West Indies, then mothballed it. Meanwhile, commissioners studied the matter. Not until 1837 did they agree on a design and build a 180-foot steamer. Called Fulton (the second), it also saw some West Indies service. The Confederate forces finally burned it when they found it in Pensacola, early in the Civil War.

Except for a steam dispatch boat, the US Navy didn't have another finished steamship until 1842. Only after civilian steam packet service was in full swing did they begin serious steam warship building. Then they did not move with anything like the speed that civilian builder Fulton had. It took another civilian outsider to jumpstart the technology of steam warships once the Civil War had begun. That was Swedish inventor John Ericsson.

Ericsson had already built a fine steam warship, the Princeton. He replaced paddle-wheels with a then-radical, but very effective, screw propeller. But his greater triumph came in 1861 when he designed the radical ironclad Monitor.

Monitor not only used a newer and better screw propeller, it also carried the first gun turret. It could use a turret with 360-degree rotation because it'd relinquished something all the ocean-going ships retained for a long time: It no longer carried sail. Without a mast, the turret could turn in any direction.

We cling to the myth that war drives technology. Yet, when we look at the details of military technology we usually see the military adapting civilian inventions. They do so slowly in peacetime, more rapidly when they're under fire. Fulton and Ericsson were first and foremost inventors. They turned to the military or to commerce -- whoever would foot the bill to support their real objective which was not winning wars, but inventing things.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

F. M. Bennett, The Steam Navy of the United States: A History of the Growth of the Steam Vessel of War in the U.S. Navy, and of the Naval Engineer Corps. (W. T. Nicholson Press, 1896): (reprinted: Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, Pubs., 1972). Both images from this source.

For an analytical discussion of my observation that war does not speed invention, see: J. H. Lienhard, How Invention Begins: Echoes of Old Voices in the Rise of New Machines, (Oxford University Press, 2006): Chapter 8.

For more on Demologos, see Episode 1674.

The USS Mississippi and the USS Missouri were the first two steam powered naval warships built by the US Navy when they finally got back into the steam warship business.