Advertising and Pricing

Today, we think about Internet advertising. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

I turn on my computer, hook up to the Internet, and immediately gain access to almost any fact in a few keystrokes. What we have today would've cost the salaries of a platoon of people in a pre-Internet life. So, what do we pay for that largesse? What's the cost of the evening news or the History Channel on TV?

We pay by watching advertising. And that's okay. It's a bother; but, now and then, even advertising tells us something we're glad to know. It strikes me as more than fair.

Now I open an 1885 British book on Carpentry and Joinery for Amateurs.This clothbound, richly-illustrated book then cost two shillings and six pence. When I convert that sum, I find that it cost less than twenty of our dollars. And printing costs have dropped dramatically since then. This was a real bargain.

Well, like our TV and Internet, the book was affordable because it carried advertising, and not just a little. Following the text is dramatically-illustrated 34-page catalog of other books, as well as every kind of hair care product.

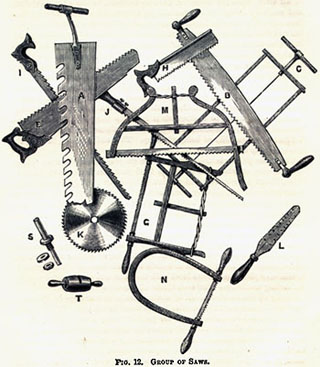

The text of the book itself tells us who the intended readers were -- middle or upper middle class, able to afford basic hand tools -- saws, augers, chisels, planes, work benches, even a treadle-operated reciprocating saw. They were, in other words, expected to have buying power.

The text of the book itself tells us who the intended readers were -- middle or upper middle class, able to afford basic hand tools -- saws, augers, chisels, planes, work benches, even a treadle-operated reciprocating saw. They were, in other words, expected to have buying power.

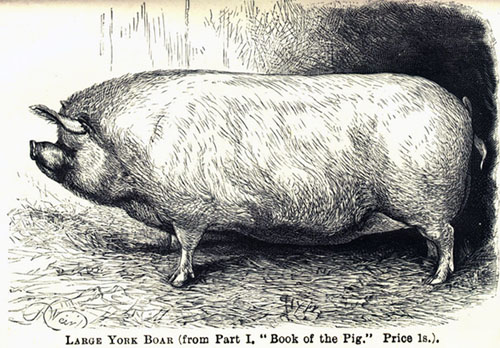

Since the readers were interested in cabinet making, they were also potential buyers of books on greenhouse management, treating diseases of dogs or of horses, on practical bee-keeping, book-binding, taxidermy. The books for sale on Art and Virtu will tell about old violins, coins, pottery and porcelain. The book Pig Keeping for Amateurs is advertised with a full page print of a prize York boar.

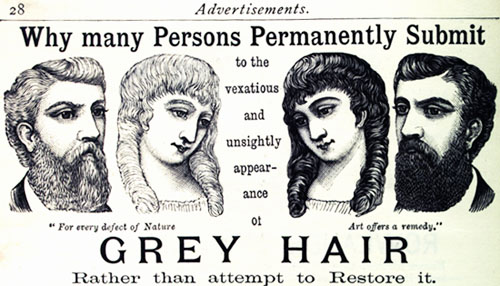

Interspersed with these titles we read: Oldrige's Balm of Columbia keeps one's hair from falling out. (Where was it when I needed it?) Latreille's Hyperion Hair Restorer will turn white hair back to its original color. The ad laments "many persons permanently submit to the vexations and unsightly appearance of grey hair." (And I thought I'd earned my grey badge of experience.) Hair is on the public's mind and, with the exception of one page devoted to upscale dog food, all the ads are about books or about hair.

Interspersed with these titles we read: Oldrige's Balm of Columbia keeps one's hair from falling out. (Where was it when I needed it?) Latreille's Hyperion Hair Restorer will turn white hair back to its original color. The ad laments "many persons permanently submit to the vexations and unsightly appearance of grey hair." (And I thought I'd earned my grey badge of experience.) Hair is on the public's mind and, with the exception of one page devoted to upscale dog food, all the ads are about books or about hair.

This series is produced by a company called The Bazaar, and the pressure of an open bazaar is ever-present as today's TV commercials. The audience is carefully targeted -- people with spare time for gardening, fly-tying, mushroom culture ... Even the text throws out bait. This book is about carpentry, but we must buy a second book if we want to master the use of a wood lathe.

Still, I shouldn't dwell only on the advertising here. The book itself is an honest product -- a lovely and detailed account of a fine domestic craft. Like our TV and Internet, it holds real quality -- in exchange for unremitting product promotion.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J. Lukin, Carpentry and Joinery for Amateurs. (London: "The Bazaar" Office, 1879). (All images from this source."