Carnegie and Young Watt

Today, Carnegies speaks through Watt. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Andrew Carnegie, was born in 1835 in Scotland. His father William moved the family to America when Andrew was 13. William was a religious dissenter with strong political views and a reverence for the democratic principles that underlay our new country.

Andrew Carnegie started out as a telegraph messenger when he was sixteen. His pay was $2.50 per week. Forty years later he was one the wealthiest industrialists in America. Yet he continued promoting populist principles, even while his company, US Steel, was at war with the union movement. Well, I do not entirely buy the idea that consistency is the prime measure of character.

Andrew Carnegie started out as a telegraph messenger when he was sixteen. His pay was $2.50 per week. Forty years later he was one the wealthiest industrialists in America. Yet he continued promoting populist principles, even while his company, US Steel, was at war with the union movement. Well, I do not entirely buy the idea that consistency is the prime measure of character.

Carnegie spent his later life dealing with his vast wealth. He became one of America's greatest philanthropists and he became a writer. His biography of another Scot, James Watt, includes an unexpected and self-revealing story. He tells how 19-year-old Watt went to London to apprentice as an instrument maker. That was normally a seven-year apprenticeship, but Watt learned it all in one year (a remarkable feat). Then he set up an instrument making and repair business in Glasgow.

The ancient Hammerman's Guild, the metalworker's union, put its foot down. Watt could not go into business until he'd done a full seven year apprenticeship. Here's Carnegie's reaction,

How the world has travelled onward since those days! ... a hundred and fifty years hence ... protective tariffs between nations and ... wars, may ... seem as ... absurd as the hammerman's rules. Even in 1905 we still have a far road to travel.

Carnegie tells how Watt did one repair job before the guild closed him down. It was for Glasgow professor Robert Dick, who was astonished by the quality of the work. So Dr. Dick found a loophole. The University was chartered by the Pope in 1451, and its grounds were sheltered from city laws. In an extraordinary move, they set Watt up as Instrument Maker to the University of Glasgow.

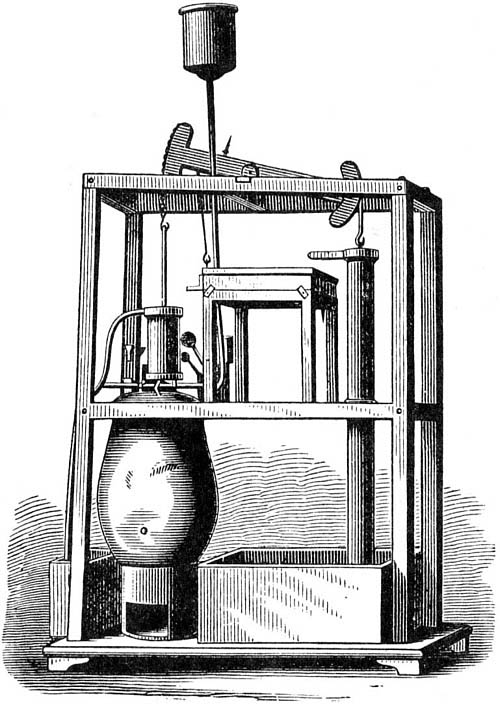

That's where 27-year-old Watt was working when another professor brought in his malfunctioning model of a Newcomen steam engine. When Watt saw how to fix it, he also saw how to improve every other steam engine. He saw how to revolutionize power technology.

Here Carnegie finds an example of all he holds dear: giving full rein to raw ability, building upon new ideas, giving the world new and better tools to work with.

Carnegie ends his telling of this event with a strange lurch -- but, when we think about it, no lurch at all. He says,

Glasgow's peculiar claim ... lies in the perfect equality of the various schools, the humanities not neglected, the sciences appreciated, neither accorded precedence.

His story of Watt curves back in upon the aim of liberal education: to create a free citizenry -- a people equipped to serve a free society. And, when Glasgow's University took in the astonishing intellect of young James Watt, that was exactly the outcome.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

A. Carnegie, James Watt. (New York: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1905): See Chapter 2. For another take on Carnegie's biography of Watt see Episode 1926.

For a full biography of Carnegie, see: D. Nasaw, Andrew Carnegie. (New York: The Penguin Press, 2006). Click here for an online biography of Carnegie.

For more on the early history of the steam engine, see J. H. Lienhard, How Invention Begins: Echoes of Old Voices in the Rise of New Machines. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006): Chapter 5.

Click here for more on the Hammerman's guild.

My thanks to listener Leif Smith for drawing my attention to this story. Images: Carnegie sketch is clipart. Newcomen engine model from an 1888 steam engine history.

The Glasgow model of Newcomen engine present to young James Watt for repair.