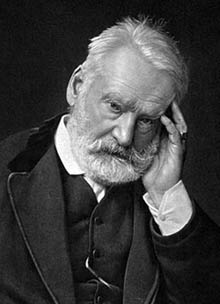

Victor Hugo and Architecture

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, our guest, historian Rob Zaretsky balances the building against the book. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Early in Victor Hugo's novel of medieval Paris, Notre Dame de Paris, the antagonist, Claude Frollo, utters a terrifying line. He directs the eyes of two visitors from a book on his desk to the massive silhouette of Notre Dame cathedral beyond his door, Frollo then announces: "This will kill that."

Early in Victor Hugo's novel of medieval Paris, Notre Dame de Paris, the antagonist, Claude Frollo, utters a terrifying line. He directs the eyes of two visitors from a book on his desk to the massive silhouette of Notre Dame cathedral beyond his door, Frollo then announces: "This will kill that."

"That" is the cathedral, "this" is the machine that produced the book on his desk: the printing press. "Small things overcome great ones," Frollo laments, "the book will kill the building."

For Frollo -- or, rather, Hugo -- the history of architecture is the history of writing. Before the printing press, mankind communicated through architecture. From Stonehenge to the Parthenon, alphabets were inscribed in "books of stone." Rows of stones were sentences, Hugo insists, while Greek columns were "hieroglyphs" pregnant with meaning.

The language of architecture climaxes in the Gothic cathedral. For centuries, Hugo asserts, priests had controlled society, and thus architecture: the squat lines of Romanesque cathedrals reflect this oppressive dogmatism. But, by the High Middle Ages, the Gothic cathedral liberates man's spirit. Poets, in the guise of architects, gave flight to their thoughts and aspirations, in flying buttresses and towering spires.

In this (admittedly) potted history of the West, the cathedral, this Goliath, inevitably falls to the David of moveable type, the book. By 1832, the year he published his novel, Hugo believed architecture had reached an impasse: architects had nothing new to say. This artistic bankruptcy was revealed in the profusion of movements that toyed with earlier styles: neo-classicism, neo-Byzantine, neo-this, neo-that. Architecture was dead, but architects hadn't yet heard the news.

Except for one: Henri Labrouste. Labrouste was still a young man building a reputation when he read Hugo. It was an epiphany -- one embodied in Labrouste's first great commission: the Ste. Genevieve Library in Paris. The library's lines are sharp and free of ornamentation: it refuses the slightest of nods to past styles. It is a machine for reading in which function alone determines its shape. Labrouste drives home the point by engraving the names of dozens of great thinkers on the exterior walls. Ornamentation? Hardly: instead, it is an enormous card catalogue: on the other side, books by these very same authors were to be shelved.

How ironic that these writers, responsible for digging architecture's grave, would be so honored by an architect. And perhaps it is even more ironic that the library lies in the shadow of the Pantheon, the French Republic's Hall of Fame. Hugo detested this neo-classical pile: a "great sponge cake," he called it. Yet in 1885, the great man was buried there. Perhaps we should just call it a machine for commemoration.

How ironic that these writers, responsible for digging architecture's grave, would be so honored by an architect. And perhaps it is even more ironic that the library lies in the shadow of the Pantheon, the French Republic's Hall of Fame. Hugo detested this neo-classical pile: a "great sponge cake," he called it. Yet in 1885, the great man was buried there. Perhaps we should just call it a machine for commemoration.

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Robert Zaretsky is professor of French history in the University of Houston Honors College, and the Department of Modern and Classical Languages. (He is the author of Nîmes at War: Religion, Politics and Public Opinion in the Department of the Gard, 1938-1944. (Penn State 1995), Cock and Bull Stories: Folco de Baroncelli and the Invention of the Camargue. (Nebraska 2004), co-editor of France at War: Vichy and the Historians. (Berg 2001), translator of Tzevtan Todorov's Voices From the Gulag. (Penn State 2000) and Frail Happiness: An Essay on Rousseau. (Penn State 2001). With John Scott, he is co-author of The Rift: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume and the Quarrel that Shook the Enlightenment. (New Haven, Yale University Press, 2007).

Victor Hugo, Notre Dame de Paris, tr. John Sturrock (New York: Penguin, 1978).

Neil Levine, The Book and the Building: Hugo's Theory of Architecture and Labrouste's Bibliothèque Ste-Geneviève. The Beaux-Arts in 19th Century French Architecture, edited by Robin Middleton (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1982).

Hugo's book has been made into many movies, usually titled The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Frollo's conversation appears on screen in the classic 1939 version The Hunchback of Notre Dame. Frollo's conversation appears on screen in the classic 1939 version with Charles Laughton as Quasimodo. See: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0031455/ Images above are courtesy of Wikipedia.

Architectural detail of buttresses on National Cathedral in Washington, DC. This is a modern building made in strict conformity with Gothic styling. Victor Hugo saw a form of language within this sort of filigreed detail. (Photo by JHL)