Faulkner and Handley Page

Today, William Faulkner takes us for a ride in a bomber. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

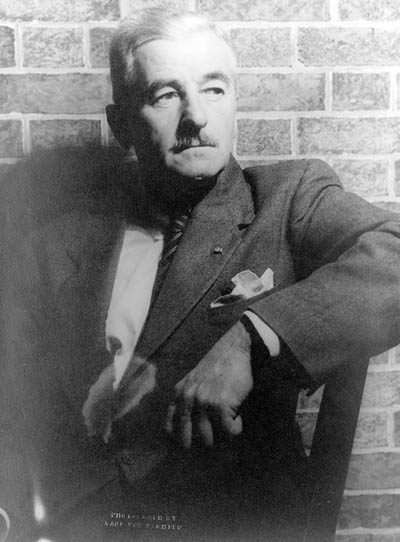

We know William Faulkner best for his dark vision of the American South. But he also supplied story lines for the movies. The 1933 movie Today We Live was cobbled together from his short story Turnabout.Faulkner's story begins one night when an American captain, a bomber pilot in WW-I, meets a drunken British lieutenant — just a kid — who serves on some sort of dispatch boat.

The pilot takes the sailor off to his base, sobers him up, and decides the next morning to show him the real war. He puts him in the gunner's cockpit of his gargantuan aeroplane. The sailor's boyishness settles into utterly cool focus when they're attacked.

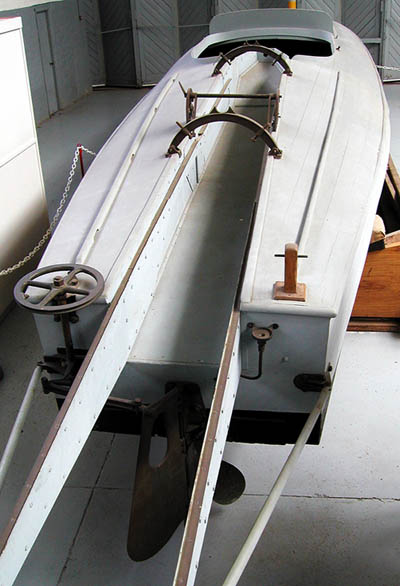

Soon after, the sailor invites the pilot for a ride in his boat. It turns out to be no service vessel at all. It's a primitive torpedo boat making hair-raisingly dangerous attacks on German shipping. The would-be dashing pilot comes back thoroughly chastened, for he's seen danger of a kind he didn't imagine.

MGM forced director Howard Hawks to include Joan Crawford in the movie (against her wishes) and doomed it with a clumsy subplot. But our interest is in Faulkner's story. He's done his homework so well we feel we're there, in that antediluvian heavy bomber.

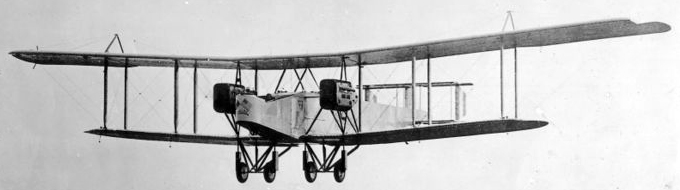

As the guns of August took their positions, both Germany and Britain dreamt up ways to bomb each other. Germany militarized her Zeppelins. Great Britain turned to the Handley Page Company for a huge aeroplane. The Admiralty had the design for Handley Page's O/100 by 1915, just six months after war began. That primitive machine had the length and wingspan of the big WW-II bombers, thirty years later. A huge biplane, powered by two engines, it carried a ton of bombs. It served in the Mediterranean as well as Europe.

(A flyer named John Alcock crashed his O/100 at sea off Greece, and was taken prisoner. When war ended, he and Arthur Brown got their hands on another early bomber, a Vickers Vimi, and used it to make the first transatlantic flight — Newfoundland to Ireland — but that was a year later.)

Faulkner takes us up in one of the 2nd-generation Handley Pages — their model O/400, then being used by the Americans. We follow the gymnastics of climbing into that great three-story high beast. We handle the forward machine guns. We release bombs from low altitudes while we cruise at a scant eighty miles an hour.

Faulkner revels in the action, but he blunts the glamour. His pilot gets a fine medal for heroism — only to learn that the kid and his torpedo boat have been anonymously destroyed on one of their Evel Knievel runs at a German vessel. In the end, he flies off to make a suicide bombing raid on the German high command.

The movies used Faulkner's stories, but rewrote his scripts. That was where they could mute the dark currents that haunted his stories. And Faulkner surely had seen the devastating potential of that great ominous aeroplane — thirty years before its time.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

P.Cooksley, British Bombers of World War I in Action. (color by Don Greer, (Carrollton, TX: Squadron/Signal Pubs., Inc., 2000), No. 202. W. Faulkner, Turnabout. Collected Stories of William Faulkner (New York: Vintage International 1995/1950): pp.: 475-509.

Scattered through the following source is a great deal of background on the movie, Today We Live: See, T. McCarthy, Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood. (New York: Grove Press, 1997)

For more on Faulkner, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Faulkner

For more on the Handley Page bombers, see:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Handley_Page_Type_O

The Handley Page O/400, image courtesy of Wikipedia

Photo of William Faulkner by Carl van Vechten

This is the type of torpedo boat described by Faulkner. It's use was made particularly dangerous, since one had to drop to torpedo out of the rear slot, then get out of the missile's way as it picked up forward speed. (Photo by JHL at the Duxford Museum, Cambridge, England.)