Making Peace with Luddism

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, our guest, historian Rob Zaretsky makes peace with his inner Luddite. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Last week I went to the local supermarket. It was just down the block, but the trip covered centuries: When I left, I was a suburbanite. But I returned as a Luddite. Let me explain.

When I arrived at the store, my toddler whispered she had to go potty. We trotted to the men's room, where I tried to create an aseptic space in the stall suitable for open-heart surgery. For my last act, I unfolded a paper cover over the glistening toilet seat as my daughter hopped impatiently from one leg to the next.

And then, whoosh! The paper cover collapsed into a watery vortex: I'd tripped the automatic flush. After my second and third efforts also failed, I tried lowering Louisa from above. As her small behind swung just above the seat, the flush's electronic eye identified it as a UFO: whoosh.

And then, whoosh! The paper cover collapsed into a watery vortex: I'd tripped the automatic flush. After my second and third efforts also failed, I tried lowering Louisa from above. As her small behind swung just above the seat, the flush's electronic eye identified it as a UFO: whoosh.

It was impossible to soothe my daughter, so we had no choice but return home. I had parked in the middle of the sweltering lot, several spaces from the nearest car. And yet, as we made our way across the melting tarmac, an SUV appeared. In the midst of the sun-blasted vastness, it pirouetted like the hippo ballerina in Disney's Fantasia. And then, thanks to its power steering -- and GPS, for all I knew -- it neatly docked right next to our car. So close to our car that the small driver could barely crack open her door and squeeze out.

I stood there, stunned. My expression caught the driver's attention, for she stopped and asked if she had parked too close. What does one say at such moments? "That's okay, I'll just lash my child to the roof."

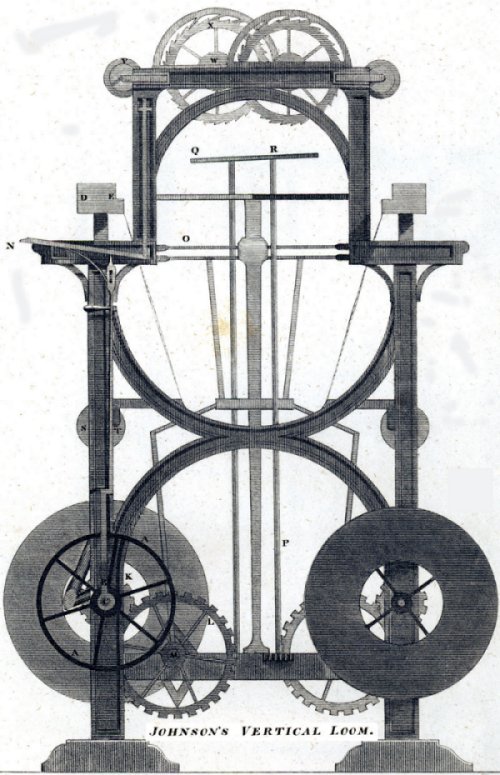

This was my Luddite moment. Lifting my child high over my head and sidling between the two cars, I thought back to early 19th century England. By then, the English reached that tipping point when the technologies meant to give us control over our lives instead snatched those lives from us. With the spread of wide-frame looms, easily used by unskilled workers, traditional weavers confronted a stark choice: resignation or rebellion.

Taking the name of a mythical weaver, Ned Ludd, they rebelled. The Luddites smashed the new tools that threatened their future with such determination that, by 1812, the monarchy feared that, along with Napoleon's France and Madison's America, it now confronted an enemy within: English artisans.

The rebellion was suppressed and skilled weavers became extinct. Yet, let's recall that the Luddites did not rebel against technology -- manual looms were also tools. They rebelled against specific uses of technology -- uses that threatened not just their livelihood, but their dignity.

I'll always plump for plumbing and even power steering. I'd be mad not to. The Luddites also would've welcomed such advances. But automatic flushes? Perhaps the Luddites would've reached for their hammers. But I'm consoled by the knowledge that time, while slower than the hammer, is an even more powerful an engine of technological discrimination.

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

E.P. Thompson, The Making of the English Working Class. (New York: Vintage Press, 1966)

For more on Ned Ludd and the Luddites, see Episode 274.

Robert Zaretsky is professor of French history in the University of Houston Honors College, and the Department of Modern and Classical Languages. (He is the author of Nîmes at War: Religion, Politics and Public Opinion in the Department of the Gard, 1938-1944. (Penn State 1995), Cock and Bull Stories: Folco de Baroncelli and the Invention of the Camargue. (Nebraska 2004), co-editor of France at War: Vichy and the Historians. (Berg 2001), translator of Tzevtan Todorov's Voices From the Gulag. (Penn State 2000) and Frail Happiness: An Essay on Rousseau. (Penn State 2001). With John Scott, he is co-author of So Great a Noise: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume and the Limits of Human Understanding. to be published by Yale University Press in 2007.

By 1832, time had indeed discriminated. the game was over for Ned Ludd's followers. This image from the 1832 Edinburgh Cyclopaedia is only one of many power looms displayed in that source.