It's All Still Greek

by Rob Zaretsky

Today, historian Rob Zaretsky travels back to the future at Delphi. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

They were running wildly around, as if their hair was on fire. The nation was in danger, yet the nature of the threat was unclear. Accounts conflicted; the "chatter" was garbled; leaders argued over strategies.

Perhaps this sounds familiar: it certainly would to an ancient Greek. This was the situation in Athens in 480 BCE, on the eve of the Persian invasion. The Greeks were at loggerheads: how to defend themselves against the approaching armies of Xerxes? For an answer, they turned to a traditional source of intelligence: the oracle at Delphi.

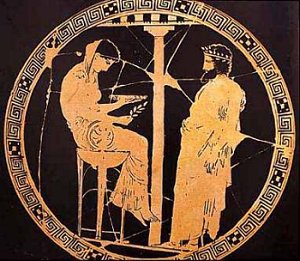

Delphi boasted a temple to Apollo, home of the Pythia, a priestess who offered counsel to supplicants seeking guidance. Her answers most often were, well, oracular: enigmatic and elusive. There were both physical and political reasons for her ambiguity.

Ancient historians, like Plutarch, report that fumes rising from the ground enveloped the Pythia, who offered her answer in a trance-like, sometimes frenzied state. In the 1990s, a team of scientists discovered an underground spring running below Delphi. It carried important traces of ethylene, a gas that smells slightly sweet -- matching Plutarch's description of the fumes as heavily perfumed -- and puts the user in states swinging from the beatific to bizarre.

Ancient historians, like Plutarch, report that fumes rising from the ground enveloped the Pythia, who offered her answer in a trance-like, sometimes frenzied state. In the 1990s, a team of scientists discovered an underground spring running below Delphi. It carried important traces of ethylene, a gas that smells slightly sweet -- matching Plutarch's description of the fumes as heavily perfumed -- and puts the user in states swinging from the beatific to bizarre.

This brings us back to 480 BCE. Did the Greeks allow themselves to be guided by a glue sniffer? Not at all. Consider both her answer to the supplicants and their response. The oracle announced: "All shall be taken by the enemy," but added: "A wall of wood which alone shall survive the foe ... shall serve you and your children ... Turn your back in retreat; on another day you shall face them."

Back in Athens, there was a welter of interpretations. Many thought the Pythia meant the thorn bushes encircling the Acropolis would save the city. An outspoken Athenian, Themistocles, disagreed: the wooden wall meant Athen's naval fleet. The city's survival lay not in the city, but in the ingenuity of its people: Athens at sea, in its hundreds of triremes, alone could defeat Xerxes. A few months later, Themistocles' interpretation was borne out: Athens defeated the Persian fleet off the coast of Salamis.

Athens survived long enough to be pestered, later in the century, by the philosopher Socrates. Delphi famously declared that Socrates was the wisest of all men. Convinced the oracle was wrong, Socrates tried to find a wiser man. But when he questioned his fellow Athenians, they revealed themselves to be wise only in their own fields. Beyond that they were ignorant. This ignorance, however, was not blissful, but tragic: these men did not know that they did not know.

Socrates concluded he was indeed the wisest man, if only because he knew he was ignorant. Then as now, this is the cardinal rule of intelligence analysis: we take from it what we bring to it: our fears and hopes, selfish biases and selfless concerns, our insight and blindness.

I'm Rob Zaretsky, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

Herodotus, The History/Heroditus. trans. David Grene (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987),

M. Lefkowitz, Women in Greek Myth. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007)

J. R. Hale, J. Zeilinga de Boer, J. P. Chanton and H. A. Spiller, Questioning the Delphic Oracle. Scientific American, September 2003. See also, Episode 1697.

Robert Zaretsky is professor of French history in the University of Houston Honors College, and the Department of Modern and Classical Languages. (He is the author of Nîmes at War: Religion, Politics and Public Opinion in the Department of the Gard, 1938-1944. (Penn State 1995), Cock and Bull Stories: Folco de Baroncelli and the Invention of the Camargue. ( Nebraska 2004), co-editor of France at War: Vichy and the Historians. (Berg 2001), translator of Tzevtan Todorov's Voices From the Gulag. (Penn State 2000) and Frail Happiness: An Essay on Rousseau. (Penn State 2001). With John Scott, he is co-author of So Great a Noise: Jean-Jacques Rousseau, David Hume and the Limits of Human Understanding. To be published by Yale University Press in 2007.

View of the temple ruins at Delphi and the valley beyond

(both images courtesy of Wikipedia)