William and George Hale

Today, the vision of a father and a son. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

William Hale was a great builder of late nineteenth-century America, and his son George Ellery Hale was a great American astronomer and astrophysicist. George did foundational theoretical work; and he built four of the world's largest telescopes.

William Hale (the father) was born in 1836 in Bedford, Massachusetts. Soon after, his family went into the paper business in Wisconsin. He was working in Chicago real estate at the time of Chicago fire, when he'd already patented a new hydraulic elevator.

Now Chicago was a burned-out begin-again place. New buildings would sprout, and their upward reach would be served by the Hale Water Counterbalance Elevator. Hale and Otis became the major American elevator tycoons. Architect Louis Sullivan called Hale one of two men "responsible for the modern office building."

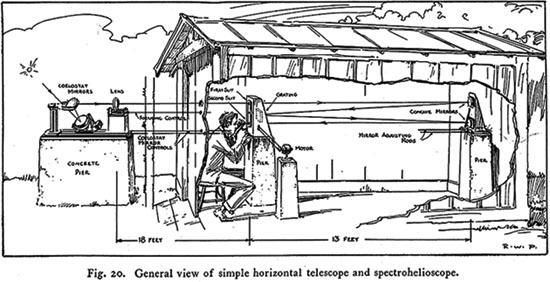

Son George was born just before William got into the elevator business. He was educated all the way through a degree from MIT, but he had a primal love for the manual arts. His first astrophysical feat appeared in his MIT thesis, where he described his invention and construction of the spectrohelioscope. That was the device that let us photograph solar flares and study their forms.

George Hale married when he graduated. The couple honeymooned in California where George saw the new Lick Observatory with its 36-inch lens. He went back and convinced his father to fund a large ten-inch telescope. That gave him the footing he needed to obtain support from industrialist Charles Yerkes to build the forty-inch Yerkes telescope in Chicago -- then largest in the world.

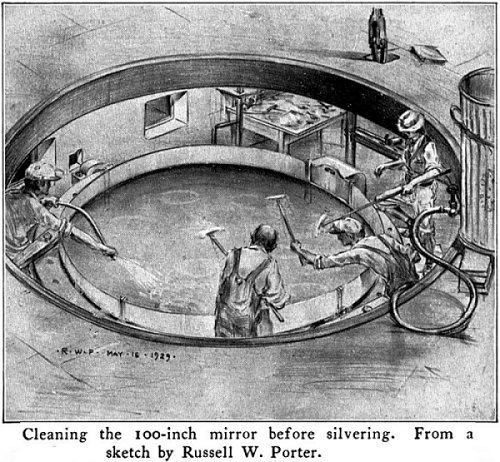

George went to his father again in 1896 and persuaded him to fund the disc for a sixty-inch telescope mirror. William agreed, and again George was responsible for building the world's largest telescope. It was finally erected on Mt. Wilson in California, ten years after William's death. Then he followed it with a 100 inch mirror. George Hale's last great telescope, the two-hundred-inch one on Mt. Palomar, was (coincidently) finished ten years after his own death in 1938.

So both these visionaries -- one the builder, the other the scientist -- worked in time frames stretching well beyond their own lives. An older William, for example, bought a horse-driven street rail system in Toledo, and made it into Toledo's electric trolley system. And an older George founded the National Research Council.

Or read George Hale's 1931 book Signals from the Stars. As he argues for the 200-inch telescope he says: In "the countless spiral nebulae far beyond our own galactic island, [where] the solar system is as a grain of sand ... we may glimpse the imprint of a Creator, infinitely above the [old] tribal deities." And, he adds, it is our first duty to discover and obey His immutable laws.

That message becomes so important today -- besieged as we are by modern theocrats striving to put ideology ahead of objective science. Well, George Hale warned us about that a lifetime ago.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

H. Wright, Hale, George Ellery, C. C. Gillispie, ed., Dictionary of Scientific Biography, Vol. VI (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1972).

See also the entry on Hale, William Ellery in The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography.

For online biographies of George Ellery Hale, click here or see Episode 1461.

G. E. Hale, Signals from the Stars, (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1931}: See especially Ch. IV, Building the 200-Inch Telescope. Both images from this source