Organizing for Disaster

Today, our guest, UH journalist Michael Berryhill, prepares for a rainy day. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Within a year of Hurricane Katrina, three major books were published about the government's failure to cope with the disaster. But none told the story of local government's biggest success: the response of the New Orleans Fire Department.

The day before Katrina arrived, the department dispersed its firefighters and equipment to sixteen pre-assigned "places of last refuge," tall, sturdy buildings on higher elevations. Each firefighter brought a three-day supply of food and water. Some of them brought their own boats.

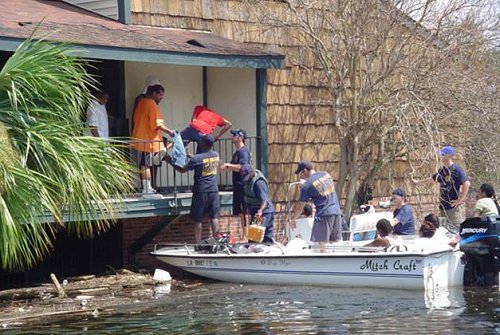

They rescued thousands of people from flooded homes during those first three days. They also fought fires, sometimes sucking toxic floodwaters through their hoses. When conditions grew too dangerous at the places of last refuge, the firefighters changed tactics. They withdrew to a college on the dry west bank of the Mississippi and created a centralized operation, improvising dormitories, a fuel depot and a repair center.

The French Quarter had escaped the flood, but a fire from one leaking gas line could have ravaged its closely packed buildings. The firefighters were ready. When 160 rail cars filled with petrochemicals derailed, the department's newly reorganized hazardous materials team answered.

All this was possible because New Orleans firefighters were trained in something called the Incident Command System. This system was developed to fight forest fires, where large numbers of people and equipment must be kept in the field for weeks at a time. That was exactly what the New Orleans firefighters were up against.

At the top of the system is the single person in charge, the incident commander. The incident commander directs four managers. The first of them, the commander of operations, directs the actions to manage the incident. The commander of planning collects and displays information about the incident and its status. Lacking computers, the planning commander for Katrina resorted to index cards and grease boards. The commander of logistics provides the resources. His guys pumped diesel from abandoned gas stations for the fire trucks. They also found an experienced chef in the ranks who could cook for 400 instead of a dozen firefighters. Last comes the finance/administration commander, who tracks the costs and maintains the records for whatever logistics buys.

The key to this system is called the span of control. Nobody supervises more than five to seven people and nobody takes orders from more than one boss.

Look back at how the firefighters worked and you wonder whether city, state and federal officials shouldn't all be trained in the Incident Command System. Imagine government officials knowing exactly what to do and exactly to whom they report. But as one New Orleans fire captain told me, "I don't know if you can take what we do and apply it to a bunch of bureaucrats."

I'm Michael Berryhill, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

This story is adapted from a long piece on the New Orleans firefighters written in the summer of 2006. I visited the city twice that summer and interviewed some of the key officials as well as rank and file members of the fire department. Among them were Richie Hampton and Tim McConnell, who led activities in the field as well as Charles Parent, the head of the New Orleans fire department.

State, County and City Emergency Responders in Texas have successfully operated under the Incident Command System for many years, even prior to Hurricane Katrina.

Michael Berryhill is assistant professor of journalism at the University of Houston's School of Communication. Before joining the faculty in August 2006, he worked for 27 years as a writer and editor for Texas publications, including the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, the Houston Chronicle, D and Houston City Magazine, and Texas Parks and Wildlife Magazine. His freelance journalism has appeared in the New York Times Magazine, Harper's and The New Republic.

Despite the floodwaters of Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans firefighters were able to answer this downtown fire. (Photo courtesy of Chris E. Mickal, district chief, New Orleans Fire Department: http://www.FIRELINEPHOTOS.com)

Firefighters rescuing stranded citizens. (Photo by Captain Richard McCurley who, on 12/2/2005, died in the line of duty enroute to an incident.)

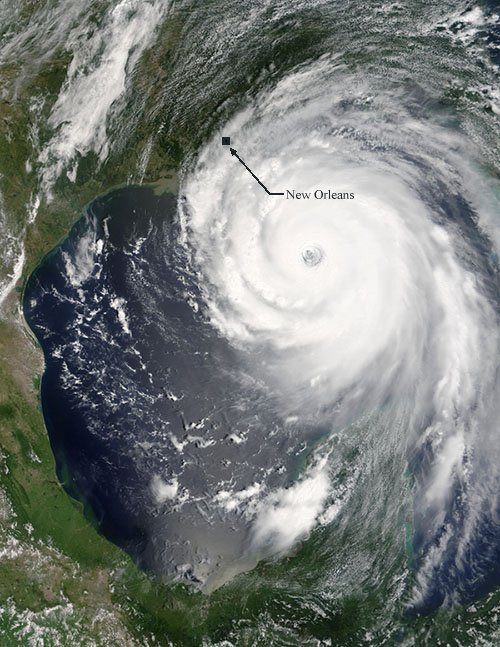

NASA image of Hurricane Katrina striking New Orleans. For a very large image, click on the picture above.