Otto Brunfels

Today, two reformations. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

We have this pretty shrub in our back yard. The flowers morph from purple through violet to white. Its common name is yesterday-today-and-tomorrow. But its formal Latin name is Brunfelsia -- after Otto Brunfels. Brunfels was born in Mainz, Germany, in 1489 -- a time when two huge revolutions were surfacing:

We have this pretty shrub in our back yard. The flowers morph from purple through violet to white. Its common name is yesterday-today-and-tomorrow. But its formal Latin name is Brunfelsia -- after Otto Brunfels. Brunfels was born in Mainz, Germany, in 1489 -- a time when two huge revolutions were surfacing:

Users of the new printing presses were just starting to include block-printed visual information in their books. They were creating the first universal descriptions of reality. At the same time, we heard the first rumblings of the Protestant Reformation.

Together, these revolutions were about to shift Earth on its axis. And they were powerfully interwoven, as we see when we trace Otto Brunfels' brief 45-year lifetime.

He was educated at the University of Mainz. Then he joined a Catholic monastery in Strasbourg. While he was there, Luther nailed his 95 theses to the Schlosskirche door. Four years later, a Protestant firebrand named Ulrich von Hutten helped influence Brunfels to leave the Catholic Church. Brunfels became pastor of one of the new Protestant churches. And he married.

He was educated at the University of Mainz. Then he joined a Catholic monastery in Strasbourg. While he was there, Luther nailed his 95 theses to the Schlosskirche door. Four years later, a Protestant firebrand named Ulrich von Hutten helped influence Brunfels to leave the Catholic Church. Brunfels became pastor of one of the new Protestant churches. And he married.

After three years of parish work, he returned to Strasbourg and opened a school. There he wrote on theology. His old mentor von Hutten had become increasingly aggressive in his support of Luther. Von Hutten had once been a friend of Erasmus, but he launched a scathing exchange of tracts with Erasmus after he failed to talk him into leaving the Catholic Church. Brunfels joined that nasty exchange by writing in defense of von Hutten.

By the way, Stanford University's motto is a line by von Hutten: Die Luft der Frieheit weht -- The Wind of Freedom Blows. Before WW-I, America began replacing Latin with German in academia, those words seemed apt. But even before von Hutten's winds of freedom began blowing through Brunfels' life, while Brunfels was still in the monastery, he'd taken an interest in medicinal herbs.

By the way, Stanford University's motto is a line by von Hutten: Die Luft der Frieheit weht -- The Wind of Freedom Blows. Before WW-I, America began replacing Latin with German in academia, those words seemed apt. But even before von Hutten's winds of freedom began blowing through Brunfels' life, while Brunfels was still in the monastery, he'd taken an interest in medicinal herbs.

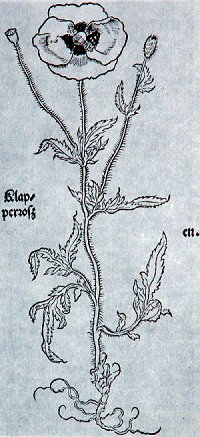

That interest lingered in his new life. In addition to writing about theology, he translated medical texts from Latin into German. Then, in 1530, he began his own three-volume treatise on herbs. To do this, he engaged a remarkable artist named Weiditz. The result is the oddest mix of soon-to-be-outdated Galenic medicine and brilliantly accurate pictures of the plants themselves. Brunfel's greatest contribution was a vast organization of pictorial material. The images long outlived the words.

And so we struggled with the new idea of a shared vocabulary. Now we would all see the same pictures, just as we'd read the Bible in our own language -- you might say the world itself changed color.

That yesterday-today-and-tomorrow shrub, with its flowers mutating -- purple to white -- makes fine counterpoint to its namesake. For Otto Brunfels was both painter and canvas -- both agent and subject -- of all the changes abroad, five hundred years ago.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

J. Stannard, Brunfels, Otto. Dictionary of Scientific Biography, C.C. Gilespie, ed. Vol. 2 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970): pp. 535-538.

L. W. Spitz. Hutten. New Catholic Encyclopedia, 2nd ed. (Detroit: Thomson/Gale; Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America, 2003.)

Images: Brunfels and von Hutten above are from old sources, courtesy of Wikipedia. The corn poppy plant is from the Brunfels/Weiditz book. Below: The two photos of a yesterday-today-and-tomorrow plant in bloom are by JHL.