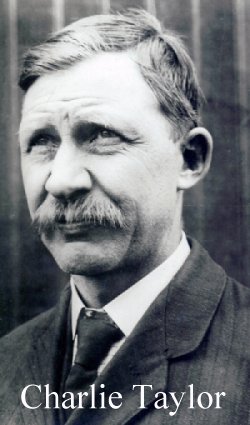

Charlie Taylor

Today, the Wright brother's engine. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents thi s series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

s series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

In 1901, the Wright brothers hired the thirty-three-year-old, cigar-smoking, cussing, machinist, Charlie Taylor to help run their bicycle shop. The abstemious Wright Brothers needed him to look after the business, since they were spending so much time developing their flying machine. Years of study, wind tunnel work on aerodynamics, and systematic glider flights, had put them far ahead of other would-be airplane makers. By 1903, their airplane was coming together nicely, but they still needed an engine.

By then, Taylor had already built the little one-cylinder engine that drove their wind tunnel. From all their careful research, they knew their airplane's engine could not weigh more than 180 pounds and it would have to deliver at least eight horsepower. The automobile makers who answered their letters said they couldn't be bothered with custom-built engines. So the Wrights turned again to Taylor.

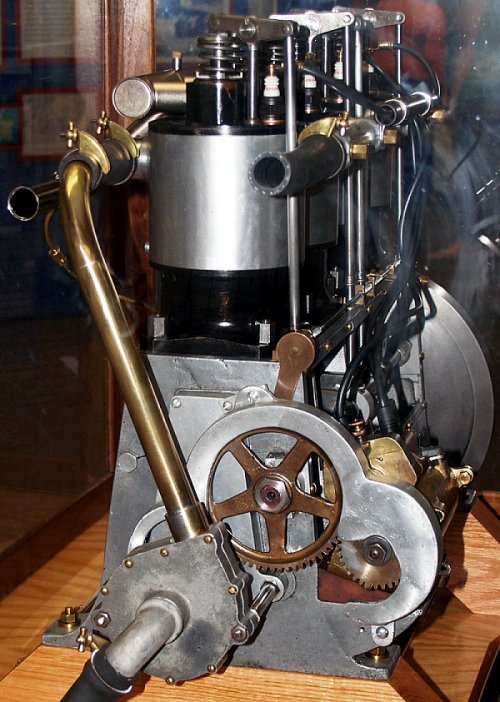

Taylor settled on a four-cylinder in-line design. It resembled turn-of-the-century automobile engines, but it had an aluminum-alloy block. Instead of spark plugs, each cylinder had contacts that opened and closed, creating a spark. The valves weren't cooled -- they simply ran red hot. The engine weighed 178 pounds, and it put out sixteen horsepower when it was cold. As the valves heated up, its output dropped to twelve horsepower. But the was still more than enough.

Taylor continued as the Wrights' mechanic. He wanted to fly, but they discouraged it. They knew flight's narcotic attraction and they'd didn't want to lose Taylor. But, when Cal Rogers made the first transcontinental flight in 1911, Taylor made the engine for Rogers' Wright-built Vin Fiz aeroplane. And he followed by car as the mechanic, for the then-lordly sum of seventy dollars a week.

So Taylor's engine propelled itself into history. But it failed to take him with it. After 1920, when he left surviving brother, Orville, his life turned sour. He tried to start a machine shop business, and it failed. His wife died. He invested in farmland near the Salton Sea and lost his shirt.

When Henry Ford began a historical reconstruction of the Dayton bicycle shop, he hired detectives to find Taylor. Taylor turned up in California earning 37 cents an hour as a machinist at North American. His coworkers had no idea that he had built the very first airplane engine. He worked with Ford's reconstruction until WW-II broke out, then vanished into another airplane plant.

After the war, Orville learned that Taylor had suffered a heart attack and could no longer work. Orville set up an eight-hundred-dollar-a-year annuity for him, but did not live to see post-war inflation reducing that sum to a pittance. Taylor ended up in the charity ward of an L.A. hospital.

It may seem a sad story. But then again, Maybe it isn't. Taylor's bones now sleep, along with those of twelve other very early aerial pioneers in a memorial shrine in Burbank, California. It's called the Portal of the Folded Wings.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

F. Howard, Orville and Wilbur. (New York: Ballantine Books, 1987). See also, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charlie_Taylor

This is a greatly revised version of Episode 254.

For more on the Vin Fiz flight, see Episode 1914.

Images of Charlie Taylor and of the Portal of the Folded Wings above are both courtesy of Wikipedia.

The New England Air Museum in Hartford, CT, identifies this as the earliest surviving Wright [Taylor] engine. Notice that it already has been given spark plugs. (Photo by JHL)