Jaywalking

Today, who owns the streets. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

Peter Norton writes about the century-old battle between automobiles and pedestrians, and his article brings up old memories. I spent so much of my childhood in the street. The street was for baseball. It was the tarmac from which my model airplanes could take off. The street was where I rode my bicycle. If it ran down a hill, it made the perfect place for sledding in winter.

But the social contract had already tilted strongly against me by the 1930s. For three decades the new motorcars had been asserting their right of place upon our streets. For you, my younger listeners, the idea of cars not having first claim upon city streets might sound very odd indeed. But they once did not.

Norton tells about a schoolteacher writing a letter to the Milwaukee Journal in 1920. She was deeply concerned with the loss of her children's play area. She asked if the streets were now to be for commercial and pleasure traffic alone. And a St. Louis dweller likewise wrote, "Children must play." The battle for the streets was older than that, of course. The Brooklyn Dodgers got their name in the 1890s, because fans had to dodge, not automobiles, but trolley cars, to get to the old Eastern Ball Park.

Norton tells about a schoolteacher writing a letter to the Milwaukee Journal in 1920. She was deeply concerned with the loss of her children's play area. She asked if the streets were now to be for commercial and pleasure traffic alone. And a St. Louis dweller likewise wrote, "Children must play." The battle for the streets was older than that, of course. The Brooklyn Dodgers got their name in the 1890s, because fans had to dodge, not automobiles, but trolley cars, to get to the old Eastern Ball Park.

The term jaywalker appeared before WW-I, as automobiles first laid their claim to streets. It derived from a slang word jay. That meant a hick, or a country bumpkin, with no understanding of the city. Meanwhile, those of us who spent our time upon the streets complained about joy-riders. It became a battle of epithets.

Commercial progress had to win out in the best interests of us all, but it was a battle. At first cities passed anti-jaywalking ordinances and police vainly tried to enforce the unenforceable.

Education had to achieve what law enforcement could not. The boy scouts became a mainstay of the campaign to educate. Starting around 1921, they passed out cards explaining the importance of staying out of traffic, and how to do so. They propelled the word jaywalking into our common vocabulary.

The matter was largely settled by the end of WW-II. I pointedly remember a 1953 Life magazine article about Einstein. It showed him walking down the right-hand side of the road to his house. A little girl wrote in to say, "Please, Dr. Einstein, walk on the left side. We don't want you hurt." Einstein thanked her and said he'd be more careful. A year and a half later, I was in Princeton and I happened to see Einstein walking down that same road. He was no longer on the right side. He was now squarely in the middle of the road.

Well, the world has made quite a few circuits about the sun since then. Einstein was raised with horse traffic. And car ownership was still something special when I was young. Princeton, no longer a sleepy little village, has its own traffic problems. And in Los Angeles, where the Dodgers now play, no one would give a moment's thought to playing stickball out upon the freeways.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

P. D. Norton, Street Rivals: Jaywalking and the Invention of the Motor Age Street. Technology and Culture, Vol. 48,No. 2., April 2007, pp. 331-359.

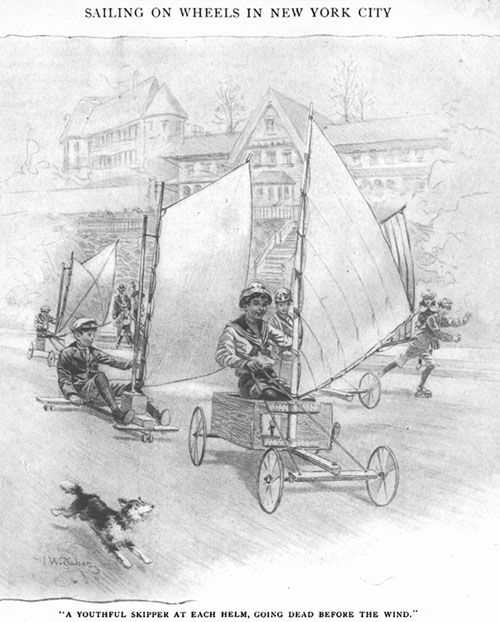

This is a telling image from an article titled Sailing on Wheels in New York City. St. Nicholas: an Illustrated Magazine for Young Folks (New York: The Century Co., Nov. 1914 to April, 1915), pp. 444-445. It celebrates the way children of 1914 have built sail-driven vehicles and run them upon a specific street -- Dyckman Street-- in New York City.