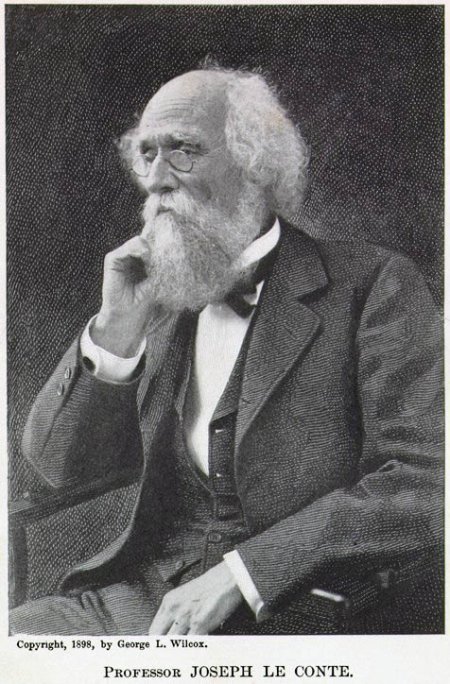

Joseph and John LeConte

Today, a tale of two slaveholders. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

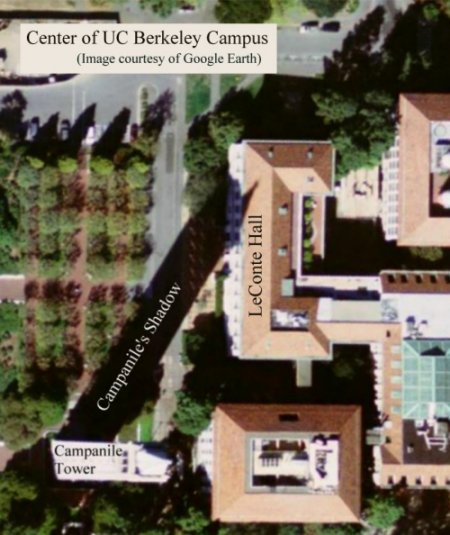

LeConte Hall is home of the Berkeley physics department. It lies in the shadow of the Campanile Tower. I once passed it daily, but hardly gave it a thought until yesterday. Then I learned about the two LeConte brothers, John and Joseph.

They were born in 1818 and '23 on a Georgia plantation. Both were old South -- paternalistic slave-owners, anti-suffrage and fundamentalist. Both went to college in Georgia. Both studied medicine in New York. John stayed to teach there for four years. Younger son Joseph did graduate work in natural history at Harvard. In 1856, both took teaching posts at the South Carolina College.

Then Civil War changed everything. Both brothers worked in the manufacture of medicines and chemicals for the Confederate Army. Their plantation finally fell to Sherman's march and they were wiped out. Their attempts to get their College moving again during reconstruction were stymied. They faced the end of an old world that'd been doomed from the start by the institution of slavery.

Finally Joseph Henry, the electrical pioneer who'd shaped the Smithsonian institution, recommended them to a new university, just getting started on the west coast. It was Berkeley. That was a devastating loss for South Carolina; but in 1869, they made a new start on the ground floor. Joseph became Berkeley's first president and John its third. LeConte Hall was named after John.

Both brothers believed that science should be based more upon observing nature than upon synthetic experimentation. That better served Joseph, who worked as a naturalist. Still, John continued as physics chair throughout his presidency and is remembered for his work on sound. His observations greatly influenced the British experimentalist John Tyndall and his treatise on sound.

An old song about the nineteenth-century west goes, "What was your name in the states?" The point is that you were a new person out west. You shook off the rubbish of your past. And that's what the LeContes did. Joseph had studied with Louis Agassiz at Harvard. Agassiz denied evolution to the end, and believed that black and white races came from separate creations.

But Joseph LeConte read Darwin with a clear head and was convinced by Darwin's own clarity. He became a peaceful advocate of evolution by natural selection. In his book, Religion and Science, he said that Genesis must be read as allegory -- that evolution did not so much contradict, as complement, the Biblical accounts.

Joseph LeConte leaves me with the old question: Do people change? He wrote that slavery should've died long before it did, but he still did not accept racial equality. When he died he'd been working on a paper against suffrage, but he'd sat on it. He'd been unsatisfied with his own arguments. So, do we change? I think we do, but not all at once. Given a few more years, I wonder how far Joseph LeConte's own evolution would have taken him.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

L. D. Stephens, Joseph LeConte: Gentle Prophet of Evolution. (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1982).

See G. Kutzbach, Leconte, John, and H. L. McKinney, LeConte, Joseph, both in the Dictionary of Scientific Biography, C.C. Gilespie, ed. Vol. 9, (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1970-1980): pp. 121-122 and pp. 122-123, respectively.

See also Wikepedia entries on Joseph and John LeConte:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_LeConte

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Eatton_Le_Conte