Before the DC-3

Today, what did we fly in before we had DC-3s? The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The Douglas DC-3 was the airplane that finally convinced our public airline travel could become commonplace. But what led up to it; by what path did early contrivances of wood and fabric finally evolve into viable airliners?

As WW-I ended, only a handful of primitive passenger and airmail services had operated, and only briefly. Sustained passenger service began flowering in 1919, just after the Armistice. And much of it was still open-cockpit service for one or two passengers.

To be attractive and profitable, aeroplanes would have to provide a comfortable cocoon for large numbers of passengers. Toward the end of the War, both sides had begun building lumbering bombers in hopes of crushing one another. Those monsters hadn't been very effective in war, but maybe they could serve as passenger carriers.

Take the Farman Goliath -- 76 mile-an-hour cruising speed, 250 mile range. Now sixty passenger models were made. Each carried twelve passengers inside, with the pilot in an open cockpit on top. The two closed cabins were outfitted and painted like Edwardian boudoirs. But, when all was said and done, this was still a primitive bomber. Airsick passengers rode in elegance, but that elegance was noisy, unheated, wind-tossed, and drafty.

Britain's Instone Airline used modified Vicker's Vimy bombers. Only three had been made in wartime. Like the Goliath, this was a biplane with an open pilot's cockpit. Ten passengers sat in padded wicker chairs along a bomb bay converted to a high-ceiling drawing room.

Travel was expensive, uncomfortable -- and very grand. It was advertised with art deco posters showing a gracious and irresistible world of tomorrow. Meanwhile airplane designers struggled to create flying machines to match that image.

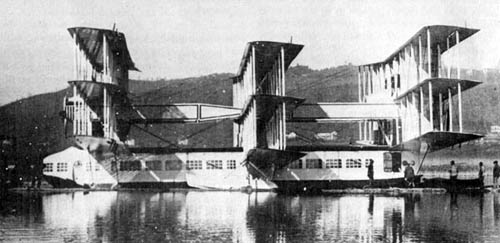

Take the notorious Caproni (Ca-60) Transaereo -- an eight-engine seaplane with nine wings in three tiers, meant to cruise 70 miles-an-hour. Its hundred-passenger body looked like a houseboat. In 1921, this monstrosity lumbered sixty feet into the air over Lake Maggiore before it crashed and broke up.

Compare the posters with actual photos of wary passengers undertaking the rigor of flight -- seventeen years after the Wright Brothers. The posters show elegant people with sinuous art deco bodies -- the photos show heavily bundled passengers, glancing warily at the sky, wondering if the game was really worth the candle.

Well, of course it was; that's how our technological species works. To turn our new machines from novelty into commonplace necessity, we shelve common sense for a season. Writer Ernest Gann was a commercial pilot. After flying earlier airplanes, he came at last to the DC-3, which finally turned flight from high adventure into routine travel. He looked at it, and sadly remarked that it was "an amiable cow ... forgiving of the clumsiest pilot."

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

E. Angelucci, World Encyclopedia of Civil Aircraft. (New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. 1982).

The Airline Builders. (Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, 1983)

The Caproni Ca-60 image above is copyright free, and courtesy of Wikipedia. Below, cover of The Wonder-Book of Aircraft, first published in 1920. This image suggests a very early airliner with the pilot still seated in an open cockpit.