Plate Tectonics

Today, our guest, geologist Peter Copeland tries to ask the right question. The University of Houston presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The theory of plate tectonics is now the unifying concept of geology. It says that Earth's outer 60 miles or so is made up of about two dozen pieces that move around relative to one another --but as fundamental concepts of science go, it's quite young.

The most respected geologists of a century ago thought that the principle reason the Earth's surface is made up of ocean basins, mountain ranges and all manner of topographic variation was vertical movements of the crust. Mountains were areas that most recently moved up; oceans were regions that had recently gone down. Much elaborate description and classification was brought forth in service of the idea that vertical motions were key.

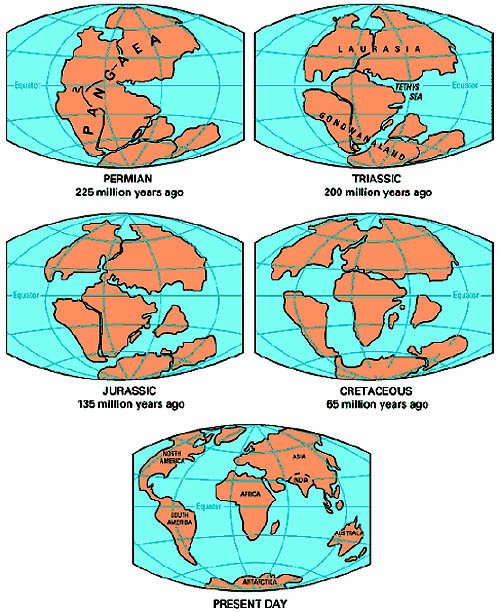

In 1914, meteorologist, Alfred Wegner, proposed a very different idea in his book The Origins of Continents and Oceans. Notice the nesting shorelines of eastern South America and western Africa: they look as though they've been broken apart like a saucer fallen to the floor. Wegner noticed this geographic similarity and compared the geology of the continents. The rocks were similar and the fossils they contained told him that they had been deposited at the same time in similar environments.

This sort of matching could be done for other continents: a jigsaw puzzle in which not only do the shapes fit together but the color of the pieces matches as well. Wegner concluded the continents drifted about the globe and that side-to-side motion was responsible for the mountains and the oceans.

In the early 20th century the various proponents of the up-and-down hypothesis of crustal evolution mostly argued for their favored idea. They didn't spend much time worrying about Wegner's idea. In retrospect, we can see flaws in the vertical motion hypothesis that might have been brought to light at the time but contemporary efforts were mostly designed to find data favoring the model; and they found it.

However, technological advances in geophysics during and following WWII allowed study of the bathymetry of the ocean floor, the nature of the Earth's magnetic field and the depth of generation of earthquakes. This brought new data that required rejection of the vertical-motion hypothesis. Wegner's original idea has evolved into the modern theory of plate tectonics in which the fundamental agent behind the formation of the mountains and the oceans, earthquakes and volcanoes and much more is horizontal motion of outermost portions of the Earth.

It took new data gathered in the 1950's and 60's to finally overturn an idea first put forth in the 19th century but this notion might have been cast aside earlier if more people had asked the question, "But what if we're wrong?" That's always a better question than, "What can I find to support my idea?"

Geologists of today find plate tectonics to be a powerful explanation of how the Earth works. But we'll only gain confidence in the theory if we continue to test it by working to topple it. Failing to break it after pushing on its weaknesses will be much more compelling than resting back and appreciating its strengths.

The penalty for asking the wrong question can easily be decades of misunderstanding.

I'm Peter Copeland at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

W. J. Kious and R. L. Tilling, This Dynamic Earth. U.S. Geological Survey, online ed. 1966: http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/dynamic.html

E. W. Moores and R. J. Twiss, 1995, Tectonics. (W.H. Freeman, 1995).

A. Wegener, The Origin of Continents and Oceans. (translated from the 4th revised German edition by John Biram) (New York: Dover Publications, 1914).

Peter Copeland is an Associate Professor in the Geoscience Dept. at the University of Houston, where he has taught for 17 years. His research has focused on the evolution of the continental crust with particular emphasis in the Himalaya and Caribbean. From 2001-2004 he was editor of the Geological Society of America Bulletin.

USGS image showing a 225 million-year history of tectonic movement.