The Flight of Voyager

Today, we fly non-stop around the world. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

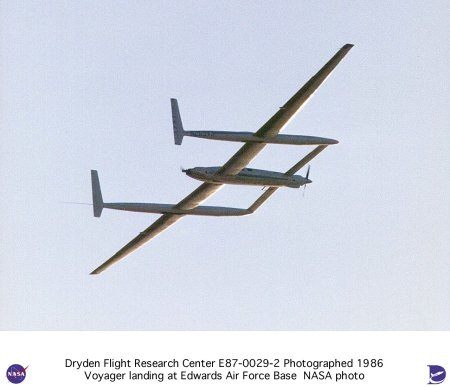

Most of us know about the 25,000-mile globe-girdling flight that Dick Rutan and Jeana Yaeger made in 1986, in their experimental airplane, Voyager. But do we fully appreciate that accomplishment? To begin with, they had to double the previous distance record to get all the way around the world in one bite. Before that flight, the competing requirements for fuel, and for the power to haul it around, seemed to diverge beyond about 12,000 miles. If you make an airplane bigger so it'll carry more fuel, the amount of fuel you need outruns the carrying capacity.

Dick Rutan's brother Burt, an airplane designer and builder, thought he could beat that equation with modern materials and an outrageous design. Five years and $2,000,000 later, the airplane was finished. It weighed just over 1800 pounds, but it had a greater wingspan than a Boeing 727. Its two light engines made up half that weight. Into this flying gas tank they poured 7000 pounds of fuel. Eighty percent of the weight of the loaded airplane was gasoline.

The fuel-filled wings so drooped on takeoff that they dragged on the runway until pieces fell off. The takeoff took 3 miles, and then this flimsy, overloaded machine spent almost three hours clawing its way up to a cruising altitude of 8000 feet.

Rutan, the more experienced of the two, did most of the flying. For nine sleepless days and nights, cramped in a frightfully noisy cabin -- only two feet wide -- Rutan and Yeager dodged storms, fought off hallucinations, and battled mechanical problems. After 216 hours in the air, they finally brought Voyager home with just 18 gallons of fuel left in her tanks.

So what did they accomplish? Well, more than you might think! Working without government or corporate support, they proved the feasibility of flying an airplane made so completely of new composite materials that it could almost have fooled a metal detector. The plane was a flying design laboratory. Their flight experience with these ideas was worth countless millions of dollars in wind-tunnel tests. And they made it clear that, if there is a distance barrier in flight, it's far greater than anyone had supposed.

But above all they showed us that the human spirit is still alive and kicking -- still willing to beat a really tough challenge for the sheer excitement of it. What they really did was to pump life into all of us by doing something extraordinary.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

(Theme music)

Heppenheimer, T.A., Voyager. Yearbook of Science and the Future. 1989 (D. Calhoun, ed.). Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc., 1989, pp. 142-159.

For a large (but slow-loading) version of this Voyager photo, click picture above.