Paper Bags

Today, flexible origami and paper bags. The University of Houston's College of Engineering presents this series about the machines that make our civilization run, and the people whose ingenuity created them.

The paper bag is a remarkable contrivance. It serves us constantly and inconspicuously. It folds flat, yet opens into a structure that can stand open upon the table while we eat our sandwiches from it and chat with friends.

The paper bag is a remarkable contrivance. It serves us constantly and inconspicuously. It folds flat, yet opens into a structure that can stand open upon the table while we eat our sandwiches from it and chat with friends.

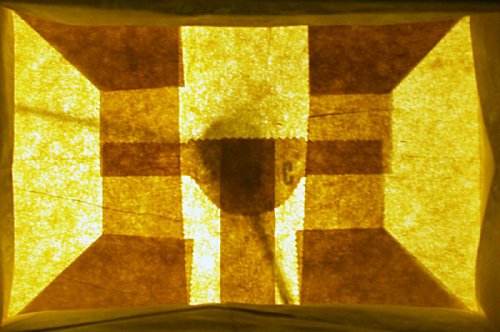

If we take the bag apart, we find it's made from a single paper cylinder. One end of the cylinder has been folded into a complex 3-dimensional pattern and finished off with a bit of paste. It would be, and once was, costly to make, because each fragile cylinder had to be folded manually into that hardy sack.

Robotics engineers have come up against another strange feature of paper bag folding. They've been looking at the origami art of paper folding in their attempt to make industrial robots more effective. They've built robots that can fold paper, and, though they've mastered much, the paper bag poses a peculiar problem.

They find two kinds of origami: rigid and flexible. The surfaces and edges of flexible origami can be bent as the objects are folded. The fancy folded napkins you find in some restaurants might be done in flexible origami. Rigid origami forms can only be folded, not bent. Imagine working with hinged metal plates instead of creased paper. Robotics engineers are doing remarkable things with a class of robots that does only rigid origami.

However, as we fold and unfold our paper bag, we have to bend the paper. And we've had paper-bag-making machines -- in effect, flexible-origami robots -- for almost a century and a half. And therein hangs the tale of Margaret Knight.

Margaret Knight was born in Maine in 1838. She went to work in the Amoskeag cotton mills at nine. When, at the age of twelve, she saw a fellow worker badly injured, she invented a device to quickly stop the machinery; and the owner put it to use.

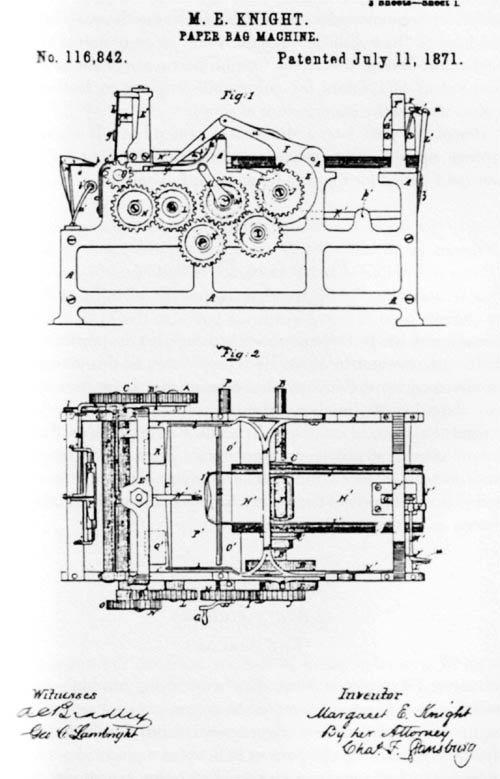

After the Civil War, she moved to Springfield, Massachusetts where she worked for the Columbia Paper mill. She studied machinery by day, and developed drawings for a bag-making machine at night. Margaret Knight hired a machinist to build a patent model, and she finally received a patent in 1871. But that was only after narrowly averting theft of the idea by an early industrial spy.

Knight went on to form the Eastern Paper Bag Company in Hartford, and she kept inventing. By the time she died at the age of 76, she held 27 patents in all. And she'd probably invented twice that number of devices with no patent protection.

Those bags are called S.O.S. for stand-on-shelf or self-opening-sacks. Some seven thousand bag-making machines operate around the world, while Margaret Knight's original machine rests in the Smithsonian Institution. And, next time I idly fold a paper swan, I'll remind myself that I haven't really come to grips with origami until I've mastered something far more beautiful -- the lovely, delicate, ever-present, brown paper sack.

Those bags are called S.O.S. for stand-on-shelf or self-opening-sacks. Some seven thousand bag-making machines operate around the world, while Margaret Knight's original machine rests in the Smithsonian Institution. And, next time I idly fold a paper swan, I'll remind myself that I haven't really come to grips with origami until I've mastered something far more beautiful -- the lovely, delicate, ever-present, brown paper sack.

I'm John Lienhard, at the University of Houston, where we're interested in the way inventive minds work.

For more on Margaret Knight, click here.

This site treats the mathematics of rigid-origami folding:

http://theory.lcs.mit.edu/classes/6.885/fall04/erik_notes/anydpi/L19_slides.pdf

All photos by JHL. This one is a view looking down into the bottom of an open bag illuminated from below; it shows details of folding and pasting.

The patent office drawing for Knight's bag-making machine